"Although the U.S. economy is still expanding, there is evidence that growth is declining around the globe. And recent surveys of top executives have suggested that business leaders are convinced the ec0nomy will slow and even fall into a recession sometime over the next two years."

Financial market fall accelerates on global growth fears

By Nick Beams

18 December 2018

US stock markets fell sharply yesterday, with the Dow down by 500 points, bringing its combined losses for the last two trading days to more than 1,000 points. The broader-based S&P 500 index was down by more than 2 percent, with the sell-off taking place across all sectors.

With all indexes now in “correction” territory, having fallen more than 10 percent since their highs, Wall Street is on track for its biggest annual decline since 2008. The Dow and the S&P 500 are set to record their worst drop for December since 1931, at the height of the Great Depression, having lost 7 percent so far for the month.

The tech-heavy Nasdaq index dropped 2.3 percent, recording a loss of 2.2 percent for the year. Market analysts described the market as “treacherous,” saying the “buy the dip” tactic, which meant that previous downturns were relatively short-lived, was not in evidence this time.

There is a confluence of factors impacting the stock market, including: fears of a global slowdown and possible recession; the ongoing impact of the US trade war against China; concerns over the future course of interest rates and what the Federal Reserve will say following its meeting on Wednesday; the impact of political turmoil in the US; the fallout of the Brexit crisis in the UK; and the developing upsurge of the working class, as reflected in the “yellow vest” movement in France.

The signs of a slowdown in global growth are most clearly expressed in China and Europe. Last week, Chinese government data showed the biggest fall in the growth rate of retail sales for 15 years and a decline in the industrial production growth rate to the lowest point in three years. There are warnings that the overall Chinese growth rate, at its lowest point since 2008-2009, could decline further next year, as US trade war measures begin to take effect.

In comments to Reuters, Changyong Rhee, a senior International Monetary Fund official for the Asia Pacific region, said the trade conflict between the US and China was already affecting business confidence in Asia.

“Investment is much weaker than expected,” he said. “My interpretation is that the confidence channel is already affecting the global economy, particularly the Asian economies.” He warned that Japan and South Korea could be among the countries hardest hit because of their dependence on exports to China.

In Europe, major economic indicators are pointing to a significant slowdown, if not a recession. According to a report in the Financial Times on Friday: “Germany is ‘stuck in a low growth phase,’ France’s private sector has fallen into contraction for the first time since 2016, and euro zone business growth has closed out 2018 at its lowest level in four years.”

The report said the business information service IHS Markit had concluded the Germany was in a period of “tepid growth,” with the “exuberant boom of 2017 now a distant memory.”

Chris Williamson, the organisation’s chief business economist, said the contraction in France was not due entirely to the series of “yellow vests” protests. Some of the slowdown reflected disruption caused by the protests, but “the weaker picture also reflects growing evidence that the underlying rate of economic growth has slowed across the euro area as whole. Companies are worried about the global economic and political climate, with trade wars and Brexit adding to increased political tensions within the euro area.”

In the United States, there are concerns that the economy will enter a period of much slower growth and lower earnings in 2019 after the effects of the “sugar hit” of the Trump administration’s corporate tax cuts wear off.

This week, all eyes will be on the statement to emerge from the meeting of the Fed on Wednesday. While a further rise in the base rate of 0.25 percent is expected—some commentators suggesting that failure to go ahead could provoke increased turbulence because it would indicate the Fed expects a worsening outlook for the economy—the key issue will be what it plans to do next year.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell offered some reassurances to the markets in November when he said the central bank’s base rate was close to neutral, indicating that it might not go ahead with the series of rises previously indicated for 2019.

President Donald Trump has continued his campaign against Fed rate rises. In a tweet issued yesterday, underscoring the delusional character of his “America First” agenda, in which turmoil in the rest of the world supposedly benefits the US economy, he wrote: “It is incredible that with a very strong dollar and virtually no inflation, the outside world is blowing up around us, Paris is burning and China way down, the Fed is even considering yet another interest rate hike. Take the Victory!”

The Fed decision will be crucial for financial markets, where there are increasing signs of a tightening of credit and concerns over stability. US credit markets are reported to be “grinding to a halt,” according to a Financial Timesreport, with “fund managers refusing to bankroll buyouts and investors shunning high-yield bond sales, as rising interest rates and market volatility weigh on sentiment.”

Not a single company has borrowed money through the $1.2 trillion high-yield, or so-called “junk bond,” market so far this month, and if that trend continues it will be the first such occurrence since November 2008, in the midst of the financial crisis.

The former chair of the Federal Reserve, Janet

Yellen, issued a warning about the state of

financial markets last October, saying there

had been a “huge deterioration” in the

standards of corporate lending.

That deterioration, however, is a direct product of the policies pursued by the Fed in the aftermath of the 2008 meltdown, as, together with other central banks, it pumped trillions of dollars into the financial system, enabling the speculation which produced the crash to continue and reach new heights.

In a comment published at the weekend, financial analyst Satyajit Das, named by Bloomberg in 2014 as one of the world’s 50 most influential financial figures, warned that what he called the “everything bubble” was deflating and a new crisis was in the making. He wrote that since 2008, governments and central banks had stabilised the situation, but the fundamental problems of high debt levels, weak banking systems and excessive financialization had not been addressed.

While not directly referring to the beginnings of an upsurge of the working class, calling it a “democracy deficit” in the advanced countries and “rising political tensions,” he pointed to the “loss of faith in supposed technocratic abilities of policymakers,” which would compound economic and financial problems.

“The political economy,” he wrote, “could then accelerate toward the critical point identified by John Maynard Keynes in 1933, where ‘we must expect the progressive breakdown of the existing structure of contract and instruments of indebtedness, accompanied by the utter discredit of orthodox leaders in finance and government, with what ultimate outcome we cannot predict.’”

Keynes did not make a prediction, but history recorded what the outcome was: worsening economic conditions, the rise of fascist and authoritarian forms of rule, trade war and economic nationalist conflicts, leading ultimately to world war. Those conditions are now rapidly returning.

Whatever the immediate outcome of the present gyrations on financial markets, they indubitably establish that none of the irresolvable contradictions of the global capitalist system has been resolved. Rather, they have intensified, and faced with an intractable economic and financial crisis, the ruling classes will lash out with even more vicious attacks on the working class, deepening the assaults of the past decade.

Eighty years ago, the international working class was unable to prevent the descent into barbarism because, while undertaking powerful struggles in the United States, Europe and Asia, it lacked a revolutionary leadership. As it once again begins to enter enormous battles against the ruling elites, it must draw the lessons of history and arm itself with a global socialist strategy to confront the great political tasks now posed by the deepening breakdown of the global capitalist order.

CEO Panic: Almost Half Say U.S. Could Be in a Recession by End of December

2:54

America’s elites are in a recession panic.

A survey of 134 American chief executive officers was conducted during last week’s Yale CEO Summit in New York, according to the New York Times. Nearly half said that the economy could enter a recession by the end of the month.

That is a stunning level of negativity given that all data show the U.S. economy is still expanding. Even the Empire State Manufacturing Survey, which came in disappointingly weak on Monday, still shows that manufacturing in New York is expanding, just at a slower pace.

The Atlanta Fed’s GDP Now, a real-time estimate of GDP based on the latest economic figures, sees fourth-quarter GDP growing at a 3 percent rate. The New York Fed’s Nowcast sees it growing at a 2.4 percent rate. Those are down from the third quarter, when the economy expanded at a 3.5 percent rate, but still far from anything suggesting a recession is about to strike.

Keep in mind that a recession is defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth. Given that there are only about two weeks left in the fourth quarter, it is all-but-impossible that we will subsequently learn that the economy had already been contracting. Economic figures get revised up and down but this would require revisions of enormous proportions. Even if the Fed shocked the market this week by hiking rates up a full percentage point–rather than the one-quarter of a point expected–the hike would slow the economy next quarter or the quarter after that. It wouldn’t retroactively repeal the growth of October and November.

A separate survey of CEOs released Monday also showed confidence in the economy has fallen sharply. According to the CEO Group:

In our most recent monthly poll of 236 U.S. CEOs, scaled on a rating of 1-10, the downward trend in CEO confidence in conditions one year from now accelerated sharply, ending the year at with a rating of 6.4 out of 10. That’s a month-over-month drop of 7% versus November, 16% since the start of the year and 13% year-over-year.CEO confidence in current business conditions also declined again in December, down 7% month-over-month to 7.2 out of 10. That level is 3% lower than the same time last year and 8% below its February peak.

So what has CEOs so glum? It is likely the stock market. CEOs of big public companies are judged by the performance of their stocks and often their compensation depends on investor gains. With the stocks of many companies deeply in negative territory for the year, and the major indexes barely hanging on to tiny gains, it may feel like we already are in a recession if you are a CEO.

The c-suites are a pretty grim place right now. In addition to the panicked CEOs, the chief financial officers are also convinced doom looms just around the corner. A recent survey found nearly half think we’ll be in a recession by end of next year and 80 percent think we’ll have entered one by the end of 2020.

Economic Optimism is Fading and Pessimism is on the Rise

3:00

The optimism that has fueled the surprisingly strong economic expansion in the first two years of the Trump administration has faded.

Just 28 percent of Americans think the economy will improve over the next 12 months, according to an NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll released Sunday. That’s about equal to the level of optimism seen in Barack Obama’s second presidential term. At the start of 2018, 35 percent expected the economy to improve.

Pessimism is on the rise. Thirty-three percent of Americans say they expect the economy will get worse, up from just 20 percent in January. That’s the first time pessimism topped optimism since 2013, when pessimism shot up from 24 percent to 42 percent over the course of just a few weeks when the country experienced a partial government shutdown in October as Republican lawmakers and President Obama failed to reach an agreement on government spending.

That spike in pessimism, however, turned out to be a head fake. The economy expanded at a 3.2 percent pace in the fourth quarter of 2013, contracted at a 1.9 percent rate between January and March of 2014, then went on to grow at around a 5 percent rate from April through September. The economy expanded in 2014 by 2.6 percent, the best performance since 2006.

President Donald Trump’s electoral victory was followed by a surge of economic optimism. In December 2016 optimism rose to 42 percent, pessimism falling to just 19 percent.

And that change in sentiment did predict economic gains. Growth rose to 2.3 percent in 2017, up from just 1.5 percent in 2016. So far in 2018, the economy appears to be headed to a 3 percent expansion.

The election of 2016 also marked a dramatic downturn in the share of people who expected the economy to be about the same. This had hovered around 50 percent for the last two years of the Obama administration but declined as many Americans shifted into a more optimistic mood.

This year has seen a shift from optimism, through “about the same,” and now into pessimism. The share of American expecting the economy to be “about the same” share climbed to 43 percent in January, up from 36 percent in the prior year. Most of that appears to have been fading optimism. And now some of those that moved into the “about the same” column have shifted further into the pessimist column.

As on many things, a sharp partisan divide runs through the economic outlook. Forty-eight percent of Republicans see things improving in the coming year, and just 12 percent see a downturn, according to the Wall Street Journal. Those proportions are reversed for Democrats.

The survey was taken in the second week of December, a period of intense volatility in the stock market.

Fed Fear: Dow Drops by More Than 500 Points

1:51

Investors on Monday stood athwart the Federal Reserve’s plans to hike rates this week, yelling “Stop!”

The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell more than 500 points. All 30 stocks in the Dow fell.

The Russell 2000 index, which tracks the stocks of smaller U.S. companies, fell 2.3 percent. That puts it into “bear market” territory, defined as a drop of 20 percent or more from the recent higher.

Breitbart TV

The S&P 500 declined 2.1 percent to its lowest level of the year. Each of the 11 sectors of the S&P declined. The Nasdaq Composite fell 2.3 percent, putting it into negative territory for the year.

The Fed will wrap-up its December policy meeting Wednesday. It is widely expected that the central bank will announce a quarter rise in its short-term interest rate target. But investors will likely focus on the Fed’s outlook for next year. Many think the Fed’s policymakers will take notice of recent signs that the economy may be slowing and signal that they no longer expect to raise rates as rapidly as previously thought.

That kind of “dove hike” is not a certainty, however. And it is not clear whether the Fed will back down far enough from its forecast of three hikes next year to calm investors worries.

Although the U.S. economy is still expanding, there is evidence that growth is declining around the globe. And recent surveys of top executives have suggested that business leaders are convinced the ec0nomy will slow and even fall into a recession sometime over the next two years. There is a possibility that this downward spiral of executive confidence could become a self-fulfilling prophecy is businesses cut back on hiring and investing in anticipation of an economic slump.

FROM THE MAGAZINE

Autumn 2018

Finance’s Lengthening Shadow

The growth of nonbank lending poses an increasing risk.Autumn 2018

Economy, finance, and budgets

A

decade ago, as the financial crisis raged, America’s banks were in ruins. Lehman Brothers, the storied 158-year-old investment house, collapsed into bankruptcy in mid-September 2008. Six months earlier, Bear Stearns, its competitor, had required a government-engineered rescue to avert the same outcome. By October, two of the nation’s largest commercial banks, Citigroup and Bank of America, needed their own government-tailored bailouts to escape failure. Smaller but still-sizable banks, such as Washington Mutual and IndyMac, died.

After the crisis, the goal was to make banks safer. The 2010 Dodd-Frank law, coupled with independent regulatory initiatives led by the Federal Reserve and other bank overseers, severely tightened banks’ ability to engage in speculative ventures, such as investing directly in hedge funds or buying and selling securities for short-term gain. The new regime made them hold more reserves, too, to backstop lending.

Yet the financial system isn’t just banks. Over the last ten years, a plethora of “nonbank” lenders, or “shadow banks”—ranging from publicly traded investment funds that purchase debt to private-equity firms loaning to companies for mergers or expansions—have expanded their presence in the financial system, and thus in the U.S. and global economies. Banks may have tighter lending standards today, but many of these other entities loosened them up. One consequence: despite a supposed crackdown on risky finance, American and global debt has climbed to an all-time high.

Banks remain hugely important, of course, but the potential for a sudden, 2008-like seizure in global credit markets increasingly lies beyond traditional banking. In 2008, government officials at least knew which institutions to rescue to avoid global economic paralysis. Next time, they may be chasing shadows.

The 2008 financial crisis vaporized 8.8 million American jobs, triggered 8 million house foreclosures, and still roils global politics. Many commentators blamed a proliferation of complex financial instruments as the primary reason for the meltdown. Notoriously, financiers had taken subprime “teaser”-rate mortgages and other low-quality loans and bundled them into opaque financial securities, such as “collateralized debt obligations,” which proved exceedingly hard for even sophisticated investors, such as the overseas banks that purchased many of them, to understand. When it turned out that some of the securities contained lots of defaulting loans—as Americans who never were financially secure enough to purchase homes struggled to pay housing debt—no one could figure out where, exactly, the bad debt was buried (many places, it turned out). Global panic ensued.

The “shadow-financing” industry played a role in the crisis, too. Many nonbank mortgage lenders had sold these bundled loans to banks, so as to make yet more bundled loans. But the locus of the 2008 crisis was traditional banks. Firms such as Citibank and Lehman had kept tens of billions of dollars of such debt and related derivative instruments on their books, and investors feared (correctly, in Lehman’s case) that future losses from these soured loans would force the institutions themselves into default, wiping out shareholders and costing bondholders money.

The ultimate cause of the crisis, however, wasn’t complex at all: a massive increase in debt, with too little capital behind it. Recall how a bank works. Like people, banks have assets and liabilities. For a person, a house or retirement account is an asset and the money he owes is a liability. A bank’s assets include the loans that it has made to customers—whether directly, in a mortgage, or indirectly, in purchasing a mortgage-backed bond. Loans and bonds are bank assets because, when all goes well, the bank collects money from them: the interest and principal that borrowers pay monthly on their mortgage, for example. A bank’s liabilities, by contrast, include the money it has borrowed from outside investors and depositors. When a customer keeps his money in the bank for safekeeping, he effectively lends it money; global investors who purchase a bank’s bonds are also lending to it. The goal, for firms as well as people, is for the worth of assets to exceed liabilities. A bank charges higher interest rates on the loans that it makes than the rates it pays to depositors and investors, so that it can turn a profit—again, when all goes well.

When the economy tanks, this system runs into two problems. First, a bank’s asset values start to fall as more people find themselves unable to pay off their mortgage or credit-card debt. Yet the bank still must repay its own debt. If the value of a bank’s assets sinks below its liabilities, the bank is effectively insolvent. To lessen this risk, regulators demand that banks hold some money in reserve: capital. Theoretically, a bank with capital equal to 10 percent of its assets could watch those assets decline in value by 10 percent without insolvency looming.

Yet investors would frown on such a thin margin, and that highlights the second problem: illiquidity. A bank might have sufficient capital to cover its losses, but if depositors and other lenders don’t agree, they may rush to take their money out—money that the bank can’t immediately provide because it has locked up the funds in long-term loans, including mortgages. During a liquidity “run,” solvent banks can turn to the Federal Reserve for emergency funding.

By 2008, bank capital levels had sunk to an all-time low; bank managers and their regulators, believing that risk could be perfectly monitored and controlled, were comfortable with the trend. By 2007, banks’ “leverage ratio”—the percentage of quality capital relative to their assets—was just 6 percent, well below the nearly 8 percent of a decade earlier. Since then, thanks to tougher rules, the leverage ratio has risen above 9 percent. Global capital ratios have risen, as well. Many analysts believe that capital requirements should be higher still, but the shift has made banks somewhat safer.

The government doesn’t mandate capital levels with the goal of keeping any particular bank safe. After all, private companies go out of business all the time, and investors in any private venture should be prepared to take that risk. The capital requirements are about keeping the economy safe. Banks tend to hold similar assets—various types of loans to people, businesses, or government. So when one bank gets into trouble, chances are that many others are suffering as well. A higher capital reserve lessens the chance of several banks veering toward insolvency simultaneously, which would drain the economy of credit. It was that threat—an abrupt shutdown of markets for all lending, to good borrowers and bad—that led Washington to bail out the financial industry (mostly the banks) in 2008.

But what if the financial industry, in creating credit, bypasses the banks? According to the global central banks and regulators who make up the international Financial Stability Board, this type of lending constitutes “shadow banking.” That’s an imprecise, overly ominous term, evoking Mafia dons writing loans to gamblers on betting slips and then kneecapping debtors who don’t pay the money back on time, but the practice is nothing so Tony Soprano-ish. The accountancy and consultancy firm Deloitte defines shadow banking, wonkily, as “a market-funded credit intermediation system involving maturity and/or liquidity transformation through securitization and secured-funding mechanisms. It exists at least partly outside of the traditional banking system and does not have government guarantees in the form of insurance or access to the central bank.”

“Shadow banking is nothing new, encompassing everything from corporate bond markets to payday lending.”

In plain English, “maturity and/or liquidity transformation” is exactly what a bank does: making a long-term loan, such as a mortgage, but funding it with short-term deposits or short-term bonds. Outside of a bank, the activity involves taking a mortgage or other kind of longer-term loan, bundling it with other loans, and selling it to investors—including pension funds, insurers, or corporations with large amounts of idle cash, like Apple—as securities that mature far more quickly than the loans they contain. The risks here are the same as at the banks, but with a twist: if people and companies can’t pay off the loans on the schedule that the lenders anticipated, all the investors risk losing money. Unlike small depositors at banks, shadow banks don’t have recourse to government deposit insurance. Nor can shadow-financing participants go to the Federal Reserve for emergency funding during a crisis—though, in many cases, they wouldn’t have to: pensioners and insurance policyholders generally don’t have the right to remove their money from pension funds and insurers overnight, as many bank investors do.

Understood broadly, shadow banking is nothing new, encompassing everything from corporate bond markets to payday lending. And much of it isn’t very shadowy; as a recent U.S. Treasury report noted, the government “prefers to transition to a different term, ‘market-based finance,’ ” because applying the term “shadow banking” to entities like insurance companies could “imply insufficient regulatory oversight,” when some such sectors (though not all) are highly regulated. It isn’t always easy to separate real banks from shadow banks, moreover. Just as before the financial crisis, banks continue to offer shadow investments, such as mortgage-backed securities or bundled corporate loans, and, conversely, banks also lend money to private-equity funds and other shadow lenders, so that they, in turn, can lend to companies.

Such market-based finance has its merits; sound reasons exist for why a pension-fund administrator doesn’t just deposit tens of billions of dollars at the bank, withdrawing the money over time to meet retirees’ needs. For people and institutions willing, and able, to take on more risk, market-based finance can offer higher interest rates—an especially important consideration when the government keeps official interest rates close to zero, as it did from 2008 to 2016. Shadow finance also offers competition for companies, people, and governments unable to borrow from banks cheaply, or whose needs—say, a multi-hundred-billion-dollar bond to buy another company—would be beyond the prudent coverage capacity of a single bank or even a group of banks.

Theoretically, bond markets and other market-based finance instruments make the financial system safer by diversifying risk. A bank holding a large concentration of loans to one company faces a major default risk. Dispersing that risk to dozens or hundreds of buyers in the global marketplace means—again, in theory—that in a default, lots of people and institutions will suffer a little pain, rather than one bank suffering a lot of pain.

But too much of a good thing is sometimes not so good, and, in this case, the extension of shadow banking threatens to reintroduce the risks that innovation was supposed to reduce. Recent growth in shadow banking isn’t serving to disperse risk or to tailor innovative products to meet borrowers’ needs. Two less promising reasons explain its expansion. One is to enable borrowers and lenders to skirt the rules—capital cushions—that constrain lending at banks. The other—after a decade of record-low, near-zero interest rates as Federal Reserve policy—is to allow borrowers and lenders to find investments that pay higher returns.

The world of market-based finance has indeed grown. Between 2002 and 2007, the eve of the financial crisis, the world’s nonbank financial assets increased from $30 trillion to $60 trillion, or 124 percent of GDP. Now these assets, at $160 trillion, constitute 148 percent of GDP. Back then, such assets made up about a quarter of the world’s financial assets; today, they account for nearly half (48 percent), reports the Financial Stability Board (FSB).

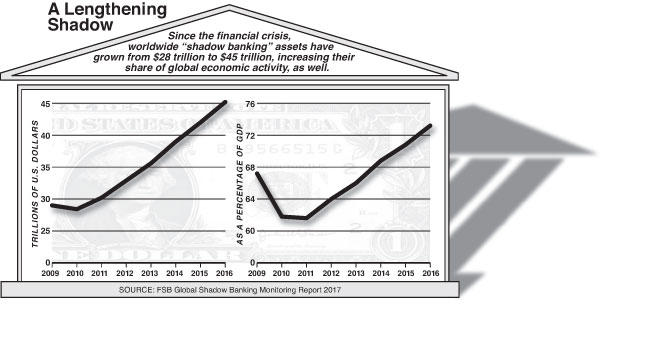

Within this pool of nonbank assets, the FSB has devised a “narrower” measure of shadow banking that identifies the types of companies likely to pose the most systemic risk to the economy—those most susceptible, that is, to sudden, bank-like liquidity or solvency panics. The FSB believes that pension funds and insurance companies could largely withstand short-term market downturns, so it doesn’t include them in this riskier category. That leaves $45 trillion in narrow shadow institutions and investments, a full 72 percent of it held in instruments “with features that make them susceptible to runs.” That’s up from $28 trillion in 2010—or from 66 percent to 73 percent of GDP.

Of that $45 trillion market, the U.S. has the largest portion: $14 trillion. (Though, as the FSB explains, separation by jurisdiction may be misleading; Chinese investment vehicles, for example, have sold hundreds of billions of dollars in credit products to local investors to spend on property abroad, affecting Western asset prices.) Compared with this $14 trillion figure, American commercial banks’ assets are worth just shy of $17 trillion, up from about $12 trillion right before the financial crisis. Banks as well as nonbank lenders have grown, in other words, but the banks have done so under far stricter oversight.

An analysis of one particular area of shadow financing shows the potential for a new type of chaos. A decade ago, an “exchange-traded fund,” or ETF, was mostly a vehicle to help people and institutions invest in stocks. An investor wanting to invest in a stock portfolio but without enough resources to buy, say, 100 shares apiece in several different companies, could purchase shares in an ETF that made such investments. These stock-backed ETFs carried risk, of course: if the stock market went down, the value of the ETF tracking the stocks would go down, too. But an investor likely could sell the fund quickly; the ETF was liquid because the underlying stocks were liquid.

Over the past decade, though, a new creature has emerged: bond-based ETFs. A bond ETF works the same way as a stock ETF: an investor interested in purchasing debt securities but without the financial resources to buy individual bonds—usually requiring several thousand dollars of outlay at once—can purchase shares in a fund that invests in these bonds. Since 2005, bond ETFs have grown from negligible to a market just shy of $800 billion—nearly 10 percent of the value of the U.S. corporate bond market.

These bond ETFs are riskier, in at least one way, than stock ETFs. Some bond ETFs, of course, invest solely in high-quality federal, municipal, and corporate debt—bonds highly unlikely to default in droves. Default, though, isn’t the only risk: suddenly higher global interest rates could cause bond funds to lose value (as new bonds, with the higher interest rates, would be more attractive). And with the exception of federal-government debt, even the highest-quality bonds aren’t as liquid as stocks; they have maturities ranging anywhere from hours remaining to 100 years.

Investors in bond-based ETFs, then, face a much bigger “liquidity” and “maturity” mismatch risk. If the investors want to sell their ETF shares in a hurry, the fund managers might not be able to sell the underlying bonds quickly to repay them, particularly in a tense market. That’s especially true, since bond markets are even less liquid than they were pre–financial crisis. Because of new regulations on “market making,” banks will be highly unlikely to buy bonds in a declining market to make a buck later, after the panic subsides.

Alook at a related type of debt-based ETF raises even bigger mismatch concerns. “In 2017, investors poured $11.5 billion into U.S. mutual funds and exchange-traded funds that invest in high-yield bank loans,” notes Douglas J. Peebles, chief investment officer of fixed-income—bonds—at the AllianceBernstein investment outfit. A high-yield bank loan is one that carries particular risk, such as a loan to a company with a poor credit rating or to a company borrowing money to merge with another firm or to expand; the “yield” refers to the higher interest rate required to compensate for this risk. Rather than keep this loan on its books, the bank is selling it, in these cases, to the exchange-traded funds that are a rising component of shadow banking.

This new demand has induced lending that otherwise wouldn’t exist—in many cases, for good reason. “The quality of today’s bank loans has declined,” Peebles observes, because “strong demand has been promoting lax lending and sketchy supply. . . . Companies know that high demand means they can borrow at favorable rates.” Further, says Peebles, “first-time, lower-rated issuers”—companies without a good track record of repaying debt—are responsible for the recent boom in loan borrowers, from fewer than 300 institutions in 2007 to closer to 900 today. The number of bank-loan ETFs (and similar “open-ended” funds) expanded from just two in 1992 to 250 in June 2018.

Peebles worries as well about the extra risk that this financing mechanism poses to investors. “In the past, banks viewed the loans as investments that would stay on their balance sheets,” he explains, but now that banks sell them to ETFs, “most investors today own high-yield bank loans through mutual funds or ETFs, highly liquid instruments. . . . But the underlying bank loan market is less liquid than the high-yield bond market,” with trades “tak[ing] weeks to settle.” He warns: “When the tide turns, strategies like these are bound to run into trouble.”

The peril to the economy isn’t just that current investors could lose money in a crisis, though big drops in asset markets typically lead people to curtail consumer spending, deepening a recession. The bigger danger is a repeat of 2008: fear of losses on existing investments might lead shadow-market lenders to cut off credit to all potential new borrowers, even worthy ones. Banks, because they’re dependent on shadow banks to buy their loans, would be unlikely to fill the vacuum. “Although non-bank credit can act as a substitute for bank credit when banks curtail the extension of credit, non-bank and bank credit can also move in lockstep, potentially amplifying credit booms and busts,” says the FSB. The porous borders between the supposedly riskier parts of the nonbank financial markets—ETFs—and the less risky ones also could work against a fast recovery in a crisis. Thanks to recent regulatory changes, insurance companies, for example, are set to become big purchasers of bond ETF shares.

Worsening this hazard, just as with the collateralized debt securities of the financial meltdown, many bond-based ETFs contain similar securities. Such duplication could eradicate the diversification benefit that the economy supposedly gets from dispersing risk. Contagion would be accelerated by the fact that debt-based ETFs, like stock-based ETFs, must “price” themselves continuously during the day, according to perceived future losses; this, in effect, introduces the risk of stock-market-style volatility into long-term bond markets. (Bond-based mutual funds, of course, have existed for decades, but they did not trade like stocks and thus did not feature this particular risk.) Via the plunging price of collateralized debt obligations, we saw, in 2008, what happened to the availability of long-term credit when exposed to the pricing signals of an equity-style crash, but those collateralized debt obligations traded far less frequently than bond ETFs do today. Bond ETFs may be more efficient, yes, in reflecting any given day’s value; that supposed benefit could also allow a panic to spread more rapidly.

During the last global panic, the answer to getting credit flowing again—so that companies could perform critical tasks, such as meeting payrolls, before revenue from sales came in—was to provide extraordinary government support to the large banks. But even if one believes that such bailouts are a sensible approach to financial crises—a highly tenuous position—how would the government provide longer-term support to hundreds of individual funds, to ensure that the broader market keeps functioning for credit-card and longer-term corporate debt? This would greatly expand the government safety net over supposedly risk-embracing financial markets—by even more than it was expanded a decade ago.

“When both regular banks and shadow banks are tapped out, we may need shadow-shadow finance to take up the slack.”

Unwise lending also harms borrowers. Private-equity firms, too, are increasingly lending companies money, instead of just buying those firms outright, their older model. As the Financial Times recently reported, private-equity funds—or, more accurately, their related private-credit funds—have more than $150 billion in money available for investment. They make loans that banks won’t, or can’t, make, though this is leading banks to take greater risks to compete. “It’s been great for borrowers,” says Richard Farley, chair of law firm Kramer Levin’s leveraged-finance group, as “there are deals that would not be financed,” or would not be financed on such favorable terms.

Competition is usually healthy, and risky finance can spark innovation that otherwise wouldn’t have happened. But easy lending can also make economic cycles more violent. Even in boom years, excess debt can plunge firms that otherwise might muddle through a recession deep into crisis, or even cause them to fail, adding to layoffs and consumer-spending cutbacks. We can see this happening already, as the Financial Times reports, with bankrupt firms like Charming Charlie, an accessories store that expanded too fast; Six Month Smiles, an orthodontic concern; and Southern Technical Institute, a for-profit technical college.

The numbers are troubling. The expansion of shadow banking has unquestionably brought a pileup of debt. The Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, a trade group, estimates that U.S. bond markets, overall, have swollen from $31 trillion to nearly $42 trillion since 2008. Federal government borrowing accounts for a lot of that, but not close to all of it. The corporate-bond market, for example, went from $5.5 trillion to $9.1 trillion over the same decade. Corporations, in other words, owe almost twice as much today in bond obligations as they did a decade ago. That’s sure to make it harder for some, at least, to recover from any future downturn.

There are policy approaches to resolving these debt issues. An unpopular idea would be to treat markets that act like banks, as banks—requiring ETFs, say, to hold the same capital cushions and adhere to the same prudence standards as banks. In the end, though, the bigger problem is cultural and political. What we’re seeing, more than a decade after the financial crisis, results from the government’s mixed signals about financial markets. On the one hand, the U.S. government, along with its global counterparts, realized in 2008 that debt had reached unsustainable levels; that’s partly why it sharply raised bank capital requirements. On the other hand, the government recognized that the economy is critically dependent on debt. Absent large increases in workers’ pay, consumer and corporate debt slowdowns would stall the economy’s until-recently modest growth. That’s why the U.S. and other Western governments have kept interest rates so low, for so long.

Thus, we find ourselves with safer banks but scarier shadows. Global debt levels are now $247 trillion, or 318 percent, of world GDP, according to the Institute of International Finance, up from $142 trillion owed in 2007, or 269 percent of GDP. When both regular banks and shadow banks are tapped out, we may have to invent shadow-shadow finance to take up the slack.

No comments:

Post a Comment