The People v. Donald J. Trump

The criminal case against him is already in the works — and it could go to trial sooner than you think.

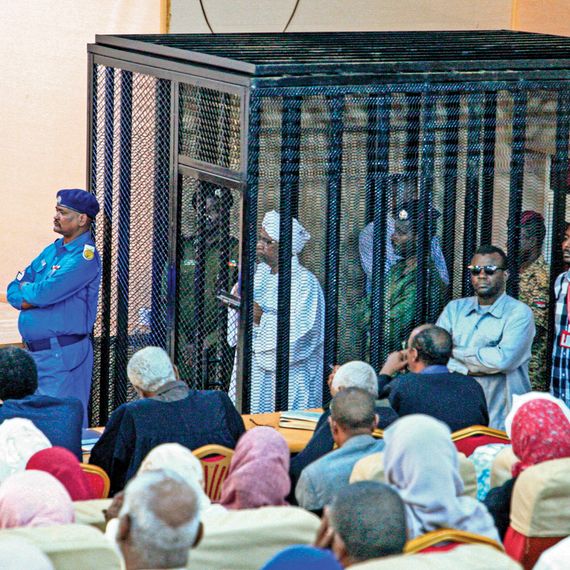

The defendant looked uncomfortable as he stood to testify in the shabby courtroom. Dressed in a dark suit and somber tie, he seemed aged, dimmed, his posture noticeably stooped. The past year had been a massive comedown for the 76-year-old former world leader. For decades, the bombastic onetime showman had danced his way past scores of lawsuits and blustered through a sprawl of scandals. Then he left office and was indicted for tax fraud. As a packed courtroom looked on, he read from a curled sheaf of papers. It seemed as though the once inconceivable was on the verge of coming to pass: The country’s former leader would be convicted and sent to a concrete cell.

The date was October 19, 2012. The man was Silvio Berlusconi, the longtime prime minister of Italy.

Here in the United States, we have never yet witnessed such an event. No commander-in-chief has been charged with a criminal offense, let alone faced prison time. But if Donald Trump loses the election in November, he will forfeit not only a sitting president’s presumptive immunity from prosecution but also the levers of power he has aggressively co-opted for his own protection. Considering the number of crimes he has committed, the time span over which he has committed them, and the range of jurisdictions in which his crimes have taken place, his potential legal exposure is breathtaking. More than a dozen investigations are already under way against him and his associates. Even if only one or two of them result in criminal charges, the proceedings that follow will make the O. J. Simpson trial look like an afternoon in traffic court.

It may seem unlikely that Trump will ever wind up in a criminal court. His entire life, after all, is one long testament to the power of getting away with things, a master class in criminality without consequences, even before he added presidentiality and all its privileges to his arsenal of defenses. As he himself once said, “When you’re a star, they let you do it.” But for all his advantages and all his enablers, including loyalists in the Justice Department and the federal judiciary, Trump now faces a level of legal risk unlike anything in his notoriously checkered past — and well beyond anything faced by any previous president leaving office. To assess the odds that he will end up on trial, and how the proceedings would unfold, I spoke with some of the country’s top prosecutors, defense attorneys, and legal scholars. For the past four years, they have been weighing the case against Trump: the evidence already gathered, the witnesses prepared to testify, the political and constitutional issues involved in prosecuting an ex-president. Once he leaves office, they agree, there is good reason to think Trump will face criminal charges. “It’s going to head toward prosecution, and the litigation is going to be fierce,” says Bennett Gershman, a professor of constitutional law at Pace Law School who served for a decade as a New York State prosecutor.

Here, according to the legal experts, is how Trump could become the first former president in American history to find himself on trial — and perhaps even behind bars.

You might think, given all the crimes Trump has bragged about committing during his time in office, that the primary path to prosecuting him would involve the U.S. Justice Department. If Joe Biden is sworn in as president in January, his attorney general will inherit a mountain of criminal evidence against Trump accumulated by Robert Mueller and a host of inspectors general and congressional oversight committees. If the DOJ’s incoming leadership green-lights an investigation of Trump after being briefed on any sensitive matters contained in the evidence, federal prosecutors will move forward“at the fastest pace they can,” says Mary McCord, the former acting assistant attorney general for national security.

They’ll have plenty of potential charges to choose from. Both Mueller and the Senate Intelligence Committee — a Republican-led panel — have extensively documented how Trump committed obstruction of justice (18 U.S. Code § 73), lied to investigators (18 U.S. Code § 1001), and conspired with Russian intelligence to commit an offense against the United States (18 U.S. Code § 371). All three crimes carry a maximum sentence of five years in prison — per charge. According to legal experts, federal prosecutors could be ready to indict Trump on one or more of these felonies as early as the first quarter of 2021.

But prosecuting Trump for any crimes he committed as president would face two significant and perhaps fatal hurdles. First, on his way out of office, Trump could decide to preemptively pardon himself. “I wouldn’t be surprised if he issues a broad, sweeping pardon for any U.S. citizen who was a subject, a target, or a person of interest of the Mueller investigation,” says Norm Eisen, who served as counsel to House Democrats during Trump’s impeachment. Since scholars are divided on whether a self-pardon would be constitutional, what happens next would depend almost entirely on which judge ruled on the issue. “One judge might say, ‘Sorry, presidential pardons is something the Constitution grants exclusively to the president, so I’m going to dismiss this,’ ” says Gershman. “Another judge might say, ‘No, the president can’t pardon himself.’ ” Either way, the case would almost certainly wind up getting litigated all the way to the Supreme Court, perhaps more than once, causing a long delay.

Even if the courts ultimately ruled a self-pardon unconstitutional, another big hurdle would remain: Trump’s claims that “executive privilege” bars prosecutors from obtaining evidence of presidential misconduct. The provision has traditionally been limited to shielding discussions between presidents and their advisers from external scrutiny. But Trump has attempted to expand the protection to include pretty much anything that he or anyone in the executive branch has ever done. William Consovoy, one of Trump’s lawyers, famously argued in federal court that even if Trump gunned someone down in the street while he was president, he could not be prosecuted for it while in office. Although the courts have repeatedly ruled against such sweeping arguments, Trump will continue to claim immunity from the judicial process after he leaves office — a surefire delaying tactic. “If federal charges were ever brought, it is unlikely that a trial would be scheduled or start anytime in the foreseeable future,” says Timothy W. Hoover, president of the New York State Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. By the time any federal charges come to trial, Trump is likely to be either senile or dead. Even if he broke the law as president, the experts agree, he may well get away with it.

But federal charges aren’t the likeliest way that The People v. Donald J. Trump will play out. State laws aren’t subject to presidential pardons, and they cover a host of crimes beyond those committed in the White House. When it comes to charging a former president, state attorneys general and county prosecutors can go places a U.S. Attorney can’t.

According to legal experts, the man most likely to drag Trump into court is the district attorney for Manhattan, Cyrus Vance Jr. It’s a surprising scenario, given Vance’s well-deserved reputation as someone who has gone easy on the rich and famous. After taking office in 2010, he sought to reduce Jeffrey Epstein’s status as a sex offender, dropped an investigation into whether Ivanka Trump and Donald Trump Jr. had committed fraud in the marketing of the Trump Soho, and initially decided not to prosecute Harvey Weinstein despite solid evidence of his sex crimes. “He has a reputation for being particularly cautious when it comes to going after rich people, because he knows that those are the ones who can afford the really formidable law firms,” says Victoria Bassetti, a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice who served on the team of lawyers that oversaw the Senate impeachment trial of Bill Clinton. “And like most prosecutors, Vance is exceptionally protective of his win-loss rate.”

But it was Vance who stepped up when the federal case against Trump faltered. “He’s a politician,” observes Martin Sheil, a former IRS criminal investigator. “He’s got his finger up. He knows which way the wind’s blowing, and he knows the wind in New York is blowing against Trump. It’s in his political interest to join that bandwagon.”

Last year, after U.S. Attorneys in the Southern District dropped their investigation into the hush money that Trump had paid Stormy Daniels, Vance took up the case. Suspecting that l’affaire Stormy might prove to be part of a larger pattern of shady dealings, his office started digging into Trump’s finances. What Vance is investigating, according to court filings, is evidence of “extensive and protracted criminal conduct at the Trump Organization,” potentially involving bank fraud, tax fraud, and insurance fraud. The New York Times has detailed how Trump and his family have long falsified records to avoid taxes, and during testimony before Congress in 2019, Trump’s longtime fixer Michael Cohen stated that Trump had inflated the value of his assets to obtain a bank loan.

Crucially, all of these alleged crimes occurred before Trump took office. That means no claims of executive privilege would apply to any charges Vance might bring, and no presidential pardon could make them go away. A whole slew of potential objections and delays would be ruled out right off the bat. What’s more, the alleged offenses took place less than six years ago, within the statute of limitation for fraud in New York. Vance, in other words, is free to go after Trump not as a crooked president but as a common crook who happened to get elected president. And the fact that he has been pursuing these cases while Trump is president is a sign that he won’t be intimidated by the stature of the office after Trump leaves it.

In writing up an indictment against Trump, Vance’s team could try to string together a laundry list of offenses in hopes of presenting an overwhelming wall of guilt. But that approach, experts warn, can become confusing. “A two- or three-count indictment is easier to explain to a jury,” says Ilene Jaroslaw, a former assistant U.S. Attorney. “If they think the person had criminal intent, it doesn’t matter if it’s two counts or 20 counts, in most cases, because the sentence will be the same.”

There are two main charges that Vance is likely to pursue. The first is falsifying business records (N.Y. Penal Law § 175.10). During Cohen’s trial, federal prosecutors filed a sentencing memorandum that explained how the Trump Organization had mischaracterized hush-money payments as “legal expenses” in its bookkeeping. Under New York law, falsifying records by itself is only a misdemeanor, but if it results in the commission of another crime, it becomes a felony. And false business records frequently lead to another offense: tax fraud (N.Y. Tax Law § 1806).

If Trump cooked his books, observes Sheil, that false information would essentially “flow into the tax returns.” The first crime begets the second, making both the bookkeeper and the tax accountant liable. “Since you have several folks involved,” Sheil says, “you could either bring a conspiracy charge, maximum sentence five years, or you could charge each individual with aiding and abetting the preparation of a false tax return, with a max sentence of three years.”

To build a fraud case against Trump, Vance subpoenaed his financial records. But those records alone won’t be enough: To secure a conviction, Vance will need to convince a jury not only that Trump cheated on his taxes but that he intended to do so. “If you just have the documents, the defense will say that defendant didn’t have criminal intent,” Jaroslaw explains. “I call it the ‘I’m an idiot’ defense: ‘I made a mistake. I didn’t mean to do anything.’ ” Unfortunately for Trump, both Cohen and his longtime accountant, Allen Weisselberg, have already signaled their willingness to cooperate with prosecutors. “What’s great about having an accountant in the witness stand is that they can tell you about the conversation they had with the client,” Jaroslaw says.

Through appeals, Trump has managed to drag out the battle over his tax returns. The case has gone all the way to the Supreme Court, back down to the district court, and back up to the appeals court. But Trump has lost at every stage, and it appears that his appeals could be exhausted this fall. Once Vance gets the tax returns, Eisen estimates, he could be ready to indict Trump as early as the second quarter of 2021.

Sheil, for one, believes Vance may already have Trump’s financial records. It’s routine procedure, he notes, for criminal tax investigators working with the Manhattan DA to obtain personal and business tax returns that are material to their inquiry. But issuing a subpoena to Trump’s accountants may have been a way to signal to them that they could face criminal charges themselves unless they cooperate in the investigation.

Once indicted, Trump would be arraigned at New York Criminal Court, a towering Art Deco building at 100 Centre Street. Since a former president with a Secret Service detail can hardly slip away unnoticed, he would likely not be required to post bail or forfeit his passport while awaiting trial. His legal team, of course, would do everything it could to draw out the proceedings. Filing appeals has always been just another day at the office for Trump, who, by some estimates, has faced more than 4,000 lawsuits during the course of his career. But this time, his legal liability would extend to numerous other state and local jurisdictions, which will also be building cases against him. “There’s like 1,037 other things where, if anybody put what he did under a microscope, they would probably find an enormous amount of financial improprieties,” says Scott Shapiro, director of the Center for Law and Philosophy at Yale University.

Even accounting for legal delays, many experts predict that Trump would go to trial in Manhattan by 2023. The proceedings would take place at the New York State Supreme Court Building. Assuming that the judge was prepared for an endless barrage of motions and objections from Trump’s defense team, the trial might move quite quickly — no longer than a few months, according to some legal observers. And given the convictions that have been handed down against many of Trump’s top advisers, there’s reason to believe that even pro-Trump jurors can be persuaded to convict him. “The evidence was overwhelming,” concluded one MAGA supporter who served on the jury that convicted Paul Manafort, Trump’s former campaign chairman. “I did not want [him] to be guilty. But he was, and no one is above the law.”

Trump’s conviction would seal the greatest downfall in American politics since Richard Nixon. Unlike his associates who were sentenced to prison on federal charges, Trump would not be eligible for a presidential pardon or commutation, even from himself. And while his lawyers would file every appeal they can think of, none of it would spare Trump the indignity of imprisonment. Unlike the federal court system, which often allows prisoners to remain free during the appeals process, state courts tend to waste no time in carrying out punishment. After someone is sentenced in New York City, their next stop is Rikers Island. Once there, as Trump awaited transfer to a state prison, the man who’d treated the presidency like a piggy bank would receive yet another handout at the public expense: a toothbrush and toothpaste, bedding, a towel, and a green plastic cup.

It Is Not Undemocratic to Call Trump’s Presidency ‘Illegitimate’

Last week, the attorney general of the United States argued that mail-in ballots are inherently corrupt, that Democrats will likely produce 100,000 fake votes in Nevada on Election Night, and that liberals are “projecting” when they accuse Republicans of undermining confidence in the integrity of the upcoming presidential election.

Here is how Bill Barr phrased these arguments in an interview with Chicago Tribune columnist John Cass:

“There’s no more secret vote with mail-in vote. A secret vote prevents selling and buying votes. So now we’re back in the business of selling and buying votes. Capricious distribution of ballots means (ballot) harvesting, undue influence, outright coercion, paying off a postman, here’s a few hundred dollars, give me some of your ballots,” the attorney general said …

“You know liberals project,” Barr said. “All this bulls— about how the president is going to stay in office and seize power? I’ve never heard of any of that crap. I mean, I’m the attorney general. I would think I would have heard about it. They are projecting. They are creating an incendiary situation where there will be loss of confidence in the vote.

“Someone will say the president just won Nevada. ‘Oh, wait a minute! We just discovered 100,000 ballots! Every vote will be counted!’ Yeah, but we don’t know where these freaking votes came from,” Barr said, promising to watch “Key Largo.”

One might write off Barr’s remarks as ironic bluster, but his comments are more concerning in context than they are in isolation. Public polling suggests that there is a stark partisan discrepancy in voting methods; Democrats are more likely to mail in their ballots, and Republicans are more likely to cast them in person. And since several swing states forbid election authorities from processing mail ballots before Election Day, this discrepancy means that it’s quite possible Donald Trump will be in the lead on November 3, only to see his vote tally eclipsed over the ensuing days. Thus, when the head of federal law enforcement suggests that mail-in ballots are inherently suspect (and that any last-minute increase in the Democratic Party’s ballot share is likely to be a product of fraud), he is priming Republican voters to reject the accuracy of any vote that Trump loses.

The president, for his part, has done the same thing — only with less subtlety. Trump has argued that we “Must know Election results on the night of the Election,” not days later, suggesting that only the votes counted on the night of November 3 will be legitimate. And he has subsequently asserted that “the only way we’re going to lose this election is if the election is rigged.”

Two years ago, when ballots counted after Election Night cost Republicans several House seats — as a result of partisan discrepancies in voting methods that were anticipated by all informed election observers — the party’s leadership baselessly accused Democrats of foul play. Meanwhile, Republicans mobilized to oppose a potential recount in Florida’s Senate race, explicitly treating a battle over whose votes would be counted as an extension of the fight for voters’ loyalties. As the New York Times reported in November 2018:

The concerted effort by Republicans in Washington and Florida to discredit the state’s recount as illegitimate and potentially rife with fraud reflects a cold political calculation: Treat the recount as the next phase of a campaign to secure the party’s majority and agenda in the Senate.

… The Republicans’ strategy in Florida reflects their experience in the 2000 presidential recount in the state. Party strategists and lawyers say they prevailed largely because they approached it as they did the race itself, with legal, political and public relations components that allowed them to outmaneuver the Democrats, who were less strategic and consistent with their lawsuit targets and public remarks about the recount.

So: The president and the head of federal law enforcement are both saying that the voting method favored by Democrats is corrupt and that the public should be suspicious of belated vote counts that redound to Joe Biden’s benefit. Republican operatives say that they view manipulating public impressions about the legitimacy of counting every vote — and seeking the help of judicial-branch allies to frustrate attempts to count all ballots — as an extension of the campaign process. And they see the 2000 election as proof of concept for this idiosyncratic mode of electioneering.

To Brookings fellow Shadi Hamid, none of this should trouble liberals.

In a column for The Atlantic this week, Hamid suggested that fears of Trump retaining power by subverting the electoral process are mere “catastrophism.” To the contrary, Hamid finds himself “truly worried about only one scenario: that Trump will win reelection and Democrats and others on the left will be unwilling, even unable, to accept the result.”

The argument that some Democrats have exaggerated Trump’s authoritarianism is defensible. Given the decentralized nature of America’s election process, there is no way for the president to “rig” the vote in any systematic fashion; if Biden wins in a landslide, there will be little that the GOP’s strategists and lawyers can do to subvert the electorate’s will. And Hamid’s concern that blue America would have difficulty reconciling itself to another unexpected loss — particularly to an impeached nativist who won fewer votes than their candidate — is also reasonable.

What is difficult to understand is how Hamid arrives at the conclusion that Democratic disaffection with a Trump victory poses a greater threat to the Republic than the president himself. Specifically, the columnist appears to think it more corrosive to democracy for liberal intellectuals to describe the Electoral College as “illegitimate” than it is for the U.S. to have a president who flouts the law, encourages political violence, strips legal status from hundreds of thousands of longtime U.S. residents, and expresses open contempt for the bedrock principles of a liberal democracy.

In isolation, an Atlantic column that makes a few fair points in service of a flawed thesis might not merit extended criticism. But in its sweeping imprecision, Hamid’s argument risks validating the Republican Party’s more demagogic efforts to portray liberal dissidence as the real authoritarianism and stigmatize modes of rhetoric and resistance that may prove necessary for disempowering the conservative movement. So it’s worth scrutinizing Hamid’s argument in some detail.

Hamid writes, “A loss by Joe Biden under [present] circumstances is the worst case not because Trump will destroy America (he can’t), but because it is the outcome most likely to undermine faith in democracy, resulting in more of the social unrest and street battles that cities including Portland, Oregon, and Seattle have seen in recent months.”

This is a curious thesis in multiple respects. Perhaps having a president who strong-arms foreign nations into investigating his domestic political opponents, defends extrajudicial killings of criminal suspects as necessary “retribution,” describes journalists as enemies of the people, and baldly lies to the public about matters as serious as a historic pandemic will not “destroy” America. But then, a bit of social unrest in a few cities won’t either. Further, it is not clear why liberals shouldn’t lose faith in the justice of their political system if such a president retains power while receiving fewer votes than his opponent yet again, nor why they should refrain from expressing their disaffection through street demonstrations — a form of mass political participation with a storied place in America’s democratic tradition.

Nevertheless, to substantiate his claim that liberals will refuse to accept Trump’s victory — thereby precipitating some unspecified social cataclysm — Hamid observes:

Liberals had enough trouble accepting the results of the 2016 election. In some sense, they never really came to terms with it. The past four years have witnessed the continuous urge to explain away the inexplicable, to find solace in the fact that the voters betrayed them. How could so many of their fellow Americans side with a racist and a fabulist, someone so callous and seemingly without empathy? It was easier to think that those Americans had been lackeys, manipulated and deceived, or that they simply hadn’t understood what was best for them …

… Liberals have convinced themselves that Republicans are, in one way or another, cheating. In addition to all of Trump’s norm-breaking, the GOP is gerrymandering, purging voter rolls, and shutting down polling places in Black neighborhoods. Yet Republicans wouldn’t have been able to do these things if they hadn’t won enough statewide and local offices in the first place. They have put themselves in a position to enact their favored redistricting and election procedures by finding candidates and pursuing policies that made them competitive in formerly Democratic states, demanding a level of party discipline that Democrats can seldom muster, and getting their supporters to turn out for down-ballot races.

Here, Hamid posits an expansive definition of what it means to “accept” the outcome of an election. It was not sufficient for Hillary Clinton to concede Trump’s victory, or for liberals to tacitly honor his right to rule by continuing to pay taxes and obey federal laws. Rather, accepting the 2016 election results would have apparently required Democrats to believe that Trump’s voters were neither “manipulated,” nor “deceived.” Given that Trump ran a historically dishonest campaign (even by the mendacious standards of American electoral politics), it is not clear why Democrats shouldn’t believe his supporters were misled (especially when individual Trump backers routinely demonstrate their own bamboozlement in interviews). Meanwhile, to the extent that liberals subscribe to a universalist conception of good government (rather than to moral relativism), they must necessarily believe that Trump’s voters did not understand what was “best for them,” in the final, enlightened analysis.

Hamid’s comments on Republican voter suppression and gerrymandering are puzzling in a similar respect. The columnist asserts that the reason the GOP succeeded in taking power in so many states over the past decade was because they pursued policies that made them competitive. This is a plausible hypothesis. But considering the unpopularity of many state-level Republican policy priorities — cutting rich people’s taxes and poor people’s Medicaid, for example — it’s not obvious that the tea-party wave was powered by the public’s thirst for small government. To the contrary, the weight of the political-science evidence would suggest that Republicans leveraged the natural advantage of out-parties in midterms, the weakness of the economy in 2010, white revanchism in the face of a Black president, and the strength of conservative propaganda networks into a landslide in spite of an economically libertarian agenda that had little innate appeal to the median voter. Republicans then used the fortuitous coincidence of their wave election with a census year to insulate their power against democratic rebuke through aggressive gerrymandering. In some places, the combination of this gerrymandering with the natural tendency of winner-take-all districting to overrepresent (predominately white) rural areas has made it effectively impossible for the Democratic Party to gain control of state governments — even when their candidates win a large majority of votes.

Hamid never explicitly says what he fears liberals will do if Trump wins reelection. If his argument is merely that Democrats must not foment secessionist movements, court faithless electors, or embrace fatalism, then it wouldn’t be objectionable. Having a lawless president secure reelection against the will of a plurality of the voting public — and with the aid of myriad acts of discriminatory disenfranchisement — will do grievous harm to our fragile facsimile of a democracy. But attempting to nullify a clear and clean Trump victory, whether through violent unrest or other means, is more likely to abet his personal authoritarianism and accelerate the Republic’s collapse than it is to curb or avert those evils. So long as an electoral path to disempowering right-wing authoritarianism remains remotely plausible, it is preferable to any alternative (especially in a nation with our history and ratio of firearms to people).

But throughout the essay, and in subsequent Twitter commentary on it, he implies a different argument — that liberals must forswear rhetoric that calls the legitimacy of America’s status-quo political institutions into question. Thus, Democrats must not call the Electoral College “illegitimate,” or the president’s voters’ “deceived,” or Republican voter suppression “cheating.” As Hamid wrote on Twitter Wednesday, “If Democrats claim EC results are ‘illegitimate’ without the popular vote, this is fundamentally undemocratic. The Electoral College is itself the product of the democratic process … What happens if we can’t change the Electoral College? Does that mean every single election the Republicans win with the EC but not the popular vote for, say, the next 20 years will be considered illegitimate? How exactly would our democracy survive that?”

Illegitimate is a word with a variety of definitions. The Electoral College awarding the presidency to a candidate who loses the popular vote is obviously legitimate in the sense of being “in accordance with the laws” (assuming Trump does not secure his Electoral College majority by blocking a full ballot count through lawsuits). But it is not necessarily legitimate in the sense of being “in accordance with the established standards” of democratic republics. Further, it is debatable whether a president elected with fewer votes than his opponent would meet the modern understanding of John Locke’s threshold for political legitimacy, which holds that a government “is not legitimate unless it is carried on with the consent of the governed.” Separately, to the extent that Donald Trump has committed “high crimes and misdemeanors” in office — as the weight of the evidence and multiple conservative members of Congress suggest — then his continued occupation of the Oval Office is at least arguably illegitimate in every sense of the word.

The point here is not merely semantic. At this moment in history, the tension between lawfulness and democratic legitimacy is acute. Trump’s handpicked head of federal law enforcement declared Wednesday night that “all prosecutorial power is vested” in himself. Barr has used that authority to provide extraordinary leniency to Trump’s allies and to threaten exceptional punishments against the administration’s adversaries. Assuming a judiciary stacked with conservative-movement operatives declines to censure Barr’s actions, his selective “sedition” prosecutions will boast formal legality. Are small-d democrats therefore obligated to declare Barr’s endeavors “legitimate”? Hamid’s argument would suggest as much. After all, Barr wouldn’t have been able to launch nakedly partisan investigations of the FBI — or float the idea of prosecuting the Democratic mayor of Seattle for her undue skepticism of law enforcement — if Trump hadn’t won an election through a democratic process in the first place.

Such reasoning is patently absurd. More importantly, it’s strategically unwise. The law is less stone than it is plastic. Popular perceptions of legitimacy inform formal definitions of legality. Throughout its history, the Supreme Court has demonstrated a sensitivity to public opinion, bending established juridical orthodoxy to appease the forces of the majority and safeguard its own authority. This point is relevant to the unlikely (but far from impossible) scenario of a contested vote this November for reasons that Republican election lawyers made explicit to the New York Times two years ago: There is a “public relations component” to winning a legal battle over how votes will be counted. Republicans are preemptively trying to delegitimize one tool that Democrats will have for shaping opinion in such a scenario: mass street protests. In recent days, the president has vowed to “put down” Election Night demonstrations with overwhelming force, while Tucker Carlson has instructed his viewers to interpret mass protests following Election Day as one facet of a looming “coup.” In this context, liberal intellectuals should be pushing back against this equation of dissent with anti-democratic insurrection, not validating it.

Finally, in the far more likely scenario that Democrats win control of the federal government through a decisive electoral victory, liberals must pressure the party to make our established political institutions more democratic. The conservative movement owes its present power to structural biases within these institutions that overrepresent its white rural base. Given that this movement has spent the Trump era broadcasting its indifference to liberal democracy — and that, in a polarized, two-party system, Republicans are unlikely to be in the wilderness for long — if Democrats secure a brief moment in power, they must use it to enhance popular sovereignty in a manner that erodes the political basis for ongoing minority-led rule by the right. Doing that will require overcoming the public’s status-quo biases and reflexive deference to established institutions — which itself will involve, among other things, contesting the legitimacy of the legislative filibuster and of a Senate that denies representation to U.S. residents in Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico, and other territories, while awarding wildly disproportionate influence to America’s white majority. (Mitch McConnell and other conservative apparatchiks are already condemning Democratic proposals to award statehood to D.C. and Puerto Rico as assaults on “the nation’s small ‘d’ democracy.”)

Hamid and other liberal critics of anti-Trump “catastrophism” are surely well intentioned. One way to read the former’s vaguely worded column is as an argument for Democrats to reject fatalism and modify their agenda to better appeal to white rural America. This would be a reasonable (if fraught) prescription. But if this was Hamid’s point, he could have made it without downplaying the authoritarianism of the present administration or implying that non-electoral forms of resistance to a lawless president are anti-democratic — or pretending that small-d democrats have nothing to fear but fear of Trump itself.