Trump: Spending Cuts, Welfare Reform Come Next

President Trump makes remarks ahead of a cabinet meeting on Nov. 20, 2017. (Photo: Screen capture/C-SPAN)

(CNSNews.com) - President Trump is going to Florida for the Thanksgiving, but he says he'll be "working very hard" while he's there.

At the start of a Cabinet meeting on Monday, Trump plugged the Republican tax plan, then said spending cuts and welfare reform are next on the list:

"We're working to reduce wasteful government spending," Trump said. "We'll be working on healthcare, infrastructure, and welfare reform. We're looking very strongly at welfare reform, and that will all take place right after taxes -- very soon, very shortly after taxes. So we'll be submitting plans on healthcare, plans on infrastructure, and plans on welfare reform -- which is desperately needed in our country -- soon after taxes.”

Trump said his Cabinet would also discuss the opioid epidemic and the need for a wall on the southern border.

"We need it," Trump said about the wall. "It's rough territory. That's where the drugs are coming in. A lot of things are happening along the border -- the southern border -- and we're going to straighten it out."

At the White House press briefing on Monday, a reporter asked spokeswoman Sarah Huckabee Sanders what Trump meant when he mentioned welfare reform:

"I think there's no secret," Sanders said, noting that Trump had spoken about it during the campaign. "And when we have specifics on what that will look like, we'll certainly announce them and roll them out. I don't anticipate that happening over the next couple of weeks. We're very focused on tax reform and making sure we get that done by the end of the year.

“But this is something that the president has a great deal of interest in, and I think you can count on probably the first part of next year seeing more specifics and details coming out on that.”

A health statistics system in shambles

The real maternal mortality rate in the United States

By Benjamin Mateus

24 November 2017

It is a known national embarrassment that among OECD countries, the United States ranks 30th in its maternal mortality death rates, only behind Mexico.

In 2000, the Millennium Summit of the United Nations established eight international development goals for the year 2015 that were adopted by the 191 member states. One of these goals was to decrease the maternal mortality rates globally by 75 percent.

A Lancet 2016 systematic analysis of this global effort highlighted that only 10 countries achieved the reduction in maternal mortality rate (MMR) of 75 percent in the period from 1990 to 2015. Overall, global maternal deaths did decline by 30 percent. Most of those reductions occurred after the Millennium declaration.

However, the MMR increased in 26 countries, including a 56 percent rise in the US from 16.9 deaths per 100,000 in 1990 to 24.7 deaths in 2015. Luxembourg, Canada and Greece were the other developed countries with a rise in MMR, but their overall rate is still two to three times lower by comparison. The other countries with rising MMR include many of the sub-Saharan African nations as well as islands such as Jamaica, Saint Lucia, American Samoa and Guam.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines maternal death as the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of the pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.

In 2000, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) set a national goal for maternal death no higher than 3.3 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2010. In that year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported an MMR rate of 13.2. Despite this national goal, the CDC reported that the US MMR had risen to 17.8 by 2009. Yet, many had argued that these reported statistics were still well below the actual magnitude. Delays in adopting the new standards for reporting maternal deaths, using nonstandard questions or having no pregnancy questions on the death certificate, made them unreliably low.

Maternal death rates are calculated by collecting the data from death certificates. These are compiled by each state and reported to the CDC’s Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance system. In the US, the manner in which death certificates were filled out and their relation to pregnancy were inconsistent and did not capture the relationship of that death to a woman’s pregnancy.

Before 2003, only three states collected data according to the WHO criteria. Fifteen states had pregnancy questions with variable timeframes from termination of pregnancy to the death, while 32 states and Washington DC did not have pregnancy questions on their death certificates.

It was only in 2003 that the HHS secretary approved revisions to the death certificate that captured pregnancy related questions. However, only four states—New York, Montana, Idaho and California—adopted these changes immediately. California elected to capture a one-year period on their death certificate versus 42 days, thereby combining both maternal and late maternal deaths. It would take another 11 years for 44 states and Washington DC to trickle in and implement these changes. Virginia was the last state to adopt the revision to the death certificate in 2017.

A damning study was published in 2016 in Obstetrics and Gynecology, titled “Recent Increases in the US Maternal Mortality Rate: Disentangling Trends from Measurement Issues.” The observational study “analyzed vital statistics from maternal mortality data from all US states in relation to the format and year of adoption of the pregnancy question [on their state death certificate].” The CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics is the official source for the reporting of MMR in the US and comparison with other nations as reviewed above. Studies conducted before 2003 had noted an under-reporting of maternal deaths in the National Vital Statistics System and are considered inaccurate. This study intended to address this discrepancy.

As the authors note, maternal deaths are rare events and therefore difficult to analyze state by state, except in the most populous. Reportedly there were 396 deaths in 2000, increasing to 856 deaths in 2014. They examined California separately because it chose to define maternal mortality within one year of pregnancy instead of 42 days per the WHO guidelines. Though Texas adopted revisions to their death certificate in 2006, they were analyzed separately because of a sharp rise in 2010 that saw maternal mortality double. The data for the other states and Washington DC were combined into four groups, according to when they initiated revisions to their death certificates.

“Unadjusted data from all states regardless of revised death certificates demonstrated that US maternal mortality more than doubled from 9.8 deaths per 100,000 in 2000 to 21.5 in 2014,” the study notes.

For group 1 (24 states and Washington DC) who did not have a pregnancy question on their death certificate in 2003, but had made revisions to their death certificates before 2013, the statistical modeling adjusted mortality rate provided a correction factor of 1.932. That means they adjusted for the undercounting in the years before revision such that the new MMR was calculated at 18.2 in 2000, increasing to 22.8 in 2014.

For group 2 (14 states) that had a nonstandard pregnancy question, the correction factor was 2.067, changing the MMR to 18.4 in 2000 and rising to 24.5 in 2014.

Group 3 included eight states that had not revised their death certificates as of late 2013 and could not be adjusted for their analysis. Not surprisingly their rates are lower, at 8.0 to 10.4 in the intervening years. Group 4 comprised three states that followed the WHO guidelines. Their MMR was 14.0 in 2000, rising to 19.9 by 2014.

Though Texas revised its death certificate in 2006, it was analyzed separately. Adjusted MMR for 2000 to 2010 was 17.7 to 18.6. After 2010, a sharp twofold rise was seen, jumping to 33.0 in 2011 and rising to 35.8 by 2014. The authors note that this data remains puzzling and unexplained. They write, “In the absence of war, natural disaster, or severe economic upheaval, the doubling of a mortality rate within a 2-year period in a state with almost 400,000 annual births seems unlikely.”

When California adopted revisions to their death certificate, their MMR doubled from 10 in 2003 to 21.5 to 2004. The state moved to implement measures that addressed postpartum hemorrhage and hypertensive disorders that contributed to the reduction in mortality as seen in the graph.

Maternal deaths revised upward

Overall, the study found that adjusted MMR for 48 states and DC was 18.8 in 2000 and rose to 23.8 by 2014, an increase of 26.6 percent. This data was based on 7,269 maternal deaths and 46,722,133 live births in the intervening years. Twenty percent of the observed increase in the unadjusted rise was the result of a real increase in maternal mortality, and 79.9 percent was the result of improved ascertainment.

It is a scandal that the richest country in the world has a chronic underfunding of the state and national vital statistics system such that accurate and reliable data cannot be obtained to enact necessary timely changes. By any standard in the financial sectors, an 80 percent disparity in such accounting would have the news media clamoring to report the event and congressional hearings would follow in days, with senators demanding answers to such negligence. But this is intentional if viewed from a socioeconomic perspective. If this were considered important, then resources would be directed to nationalizing and augmenting the woefully lacking maternal services in the US.

Four million women give birth each year in the US. Pregnancy remains the top reason for admission to the hospital. Where such statistics could garner attention and demand action, for nearly 15 years we have remained blind to this existing travesty. The US has no national review of maternal deaths.

Given the projected shortage of 8,000 to 9,000 physicians and midwives by 2023, the impending cuts to Medicare, and virtually zero interest within the two big business parties to address the crisis of maternal health care, there is little chance to correct this without a concerted effort on the part of the working class to demand accountability as part of the overall fight to replace the for-profit health care system with socialized medicine.

FROM THE MAGAZINE

Autumn 2017

Why America Can’t Lower Child-Poverty Rates

Allowing millions of low-skilled immigrants into the U.S. every year swells the ranks of the poor.Autumn 2017

Articles about America’s high levels of child poverty are a media evergreen. Here’s a typical entry, courtesy of the New York Times’s Eduardo Porter: “The percentage of children who are poor is more than three times as high in the United States as it is in Norway or the Netherlands. America has a larger proportion of poor children than Russia.” That’s right: Russia.

Outrageous as they seem, the assertions are true—at least in the sense that they line up with official statistics from government agencies and reputable nongovernmental organizations like the OECD and UNICEF. International comparisons of the sort that Porter makes, though, should be accompanied by a forest of asterisks. Data limitations, varying definitions of poverty, and other wonky problems are rampant in these discussions.

The lousy child-poverty numbers should come with another qualifying asterisk, pointing to a very American reality. Before Europe’s recent migration crisis, the United States was the only developed country consistently to import millions of very poor, low-skilled families, from some of the most destitute places on earth—especially from undeveloped areas of Latin America—into its communities, schools, and hospitals. Let’s just say that Russia doesn’t care to do this—and, until recently, Norway and the Netherlands didn’t, either. Both policymakers and pundits prefer silence on the relationship between America’s immigration system and poverty, and it’s easy to see why. The subject pushes us headlong into the sort of wrenching trade-offs that politicians and advocates prefer to avoid. Here’s the problem in a nutshell: you can allow mass low-skilled immigration, which many on the left and the right—and probably most poverty mavens—consider humane and quintessentially American. But if you do, pursuing the equally humane goal of substantially reducing child poverty becomes a lot harder.

In 1964, the federal government settled on a standard definition of poverty: an income less than three times the value of a hypothetical basic food basket. (That approach has its flaws, but it’s the measure used in the United States, so we’ll stick with it.) Back then, close to 23 percent of American kids were poor. With the important exception of the years between 1999 and 2007—following the introduction of welfare reform in 1996—when it declined to 16 percent, child poverty has bounced within three points of 20 percent since 1980. Currently, about 18 percent of kids are below the poverty line, amounting to 13,250,000 children. Other Anglo countries have lower child-poverty rates: the OECD puts Canada’s at 15 percent, with the United Kingdom and Australia lower still, between 11 percent and 13 percent. The lowest levels of all—under 10 percent—are found in the Nordic countries: Denmark, Norway, Iceland, and Finland.

How does immigration affect those post-1964 American child-poverty figures? Until 1980, it didn’t. The 1924 Immigration Act sharply reduced the number of immigrants from poorer Eastern European and southern countries, and it altogether banned Asians. (Mexicans, who had come to the U.S. as temporary agricultural workers and generally returned to their home country, weren’t imagined as potential citizens and thus were not subject to restrictive quotas.) The relatively small number of immigrants settling in the U.S. tended to be from affluent nations and had commensurate skills. According to the Migration Policy Institute, in 1970, immigrant children were less likely to be poor than were the children of native-born Americans.

By 1980, chiefly because of the 1965 Immigration and Naturalization Act, the situation had reversed: immigrant kids were now poorer than native-born ones. That 1965 law, overturning the 1924 restrictions, made “family preference” a cornerstone of immigration policy—and, as it turned out, that meant a growing number of new Americans hailing from less-developed countries and lacking skills. The income gap between immigrant and native children widened. As of 1990, immigrant kids had poverty rates 50 percent higher than their native counterparts. At the turn of the millennium, more than one-fifth of immigrant children, compared with just 9 percent of non-Hispanic white kids, were classified as poor. Today, according to Center for Immigration Studies estimates, 31.1 percent of the poor under 18 are either immigrants or the American-born kids of immigrant parents.

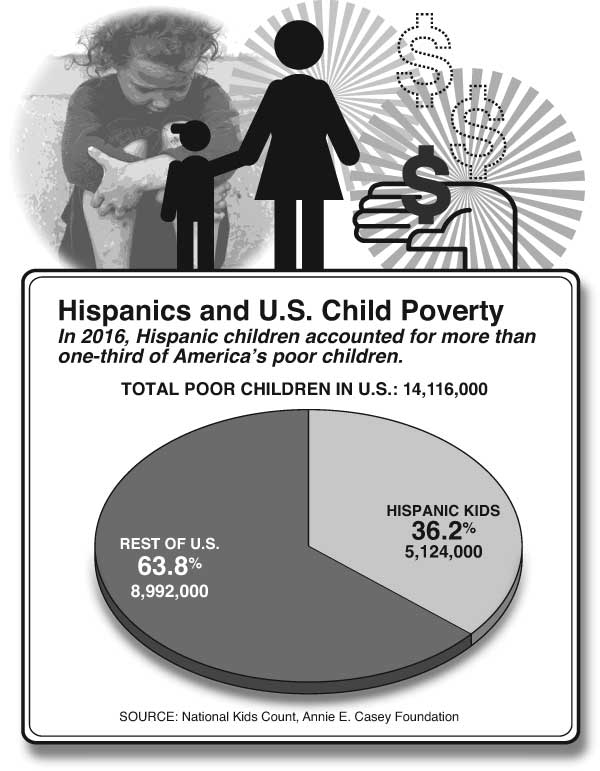

Perhaps the most uncomfortable truth about these figures, and surely one reason they don’t often show up in media accounts, is that a large majority of America’s poor immigrant children—and, at this point, a large fraction of all its poor children—are Hispanic (see chart below). The U.S. started collecting separate poverty data on Hispanics in 1972. That year, 22.8 percent of those originally from Spanish-language countries of Latin America were poor. The percentage hasn’t risen that dramatically since then; it’s now at 25.6 percent. But because the Hispanic population in America quintupled during those years, these immigrants substantially expanded the nation’s poverty rolls. Hispanics are now the largest U.S. immigrant group by far—and the lowest-skilled. Pew estimates that Hispanics accounted for more than half the 22-million-person rise in the official poverty numbers between 1972 and 2012. Robert Samuelson of the Washington Post found that, between 1990 and 2016, Hispanics drove nearly three-quarters of the increase in the nation’s poverty population from 33.6 million to 40.6 million.

Ironically, then, at the same time that America’s War on Poverty was putting a spotlight on poor children, the new immigration system was steadily making the problem worse. In 1980, only 9 percent of American children were Hispanic. By 2009, that number had climbed to 22 percent. Almost two-thirds of these children were first- or second-generation immigrants, most of whose parents were needy. Nowadays, 31 percent of the country’s Hispanic children are in poverty. That percentage remains somewhat lower than the 36 percent of black children who are poor, true; but because the raw number of poor Hispanic kids—5.1 million—is so much higher (poor black children number 3.7 million), they make up by far the largest group in the child-poverty statistics. As of 2016, Hispanic children account for more than one-third of America’s poor children. Between 1999 and 2008 alone, the U.S. added 1.8 million children to the poverty rolls; the Center for Immigration Studies reports that immigrants accounted for 45 percent of them.

Let’s be clear: Hispanic immigration isn’t the only reason that the U.S. has such troubling child-poverty rates. Other immigrant groups, such as North Africans and Laotians, add to the ranks of the under-18 poor. And American Indians have the highest rates of child poverty of all ethnic and racial groups. These are relatively small populations, however; combine Indians and Laotians, and you get fewer than a half-million poor children—a small chunk of the 14-plus million total.

Even if we were following the immigration quotas set in 1924, the U.S. would be something of a child-poverty outlier. The nation’s biggest embarrassment is the alarming percentage of black children living in impoverished homes. Unsurprisingly, before the civil rights movement, the numbers were higher; in 1966, almost 42 percent of black kids were poor. But those percentages started to improve in the later 1960s and in the 1970s. Then they soared again. By the 1980s and early 1990s, black child poverty was hovering miserably between 42 percent and almost 47 percent. Researchers attribute the lack of progress to the explosion in single-parent black families and welfare use. The current percentage of black kids living with a single mother—66 percent—far surpasses that of any other demographic group. The 1996 welfare-reform bill and a strong economy helped bring black child poverty below 40 percent, a public-policy success—but the numbers remain far too high.

Policymakers and pundits prefer silence on the relationship between America’s immigration system and poverty.

Immigrant poverty, though usually lumped within a single “child-poverty” number, belongs in a different category from black or Native American poverty. After all, immigrants voluntarily came to the United States, usually seeking opportunity. And immigrants of the past often found it. The reality of American upward mobility helps explain why, despite real hardships, poor immigrant childhood became such a powerful theme in American life and literature. Think of classic coming-of-age novels like Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (about Irish immigrants), Henry Roth’s Call It Sleep (Jewish immigrants), and Paule Marshall’s Brown Girl, Brownstones (West Indians), all set in the first decades of the twentieth century. With low pay, miserable work conditions, and unreliable hours, the immigrant groups that such novels depicted so realistically were as poor as—and arguably more openly discriminated against than—today’s Mexicans or Bangladeshis.

Their children, though, didn’t need a ton of education to leave the hard-knocks life behind. While schools of that era were doubtless more committed to assimilating young newcomers than are today’s diversity-celebrating institutions, sky-high dropout rates limited their impact. At the turn of the twentieth century, only 5 percent of the total population graduated from high school; the rate among immigrants would have been even lower. That doesn’t mean that education brought no advantages. Though economist George Borjas notes that endemic truancy and interrupted studies had ripple effects on incomes into following generations, the pre–World War II industrial economy offered a “range of blue collar opportunities” for immigrant children, as sociologists Roger Waldinger and Joel Perlman observe, and it required “only modest educations to move a notch or two above their parents.” It may have taken more than one generation, but most immigrant families could expect, if not Horatio Alger–style ascents, at least middle-class stability over time.

America’s economy has transformed in ways that have blocked many of the avenues to upward mobility available to the immigrant families of the past. The kind of middle-skilled jobs that once fed the aspirations of low-income strivers are withering. “Modest educations” will no longer raise poor immigrant children above their parents’ station. Drop out of high school, and you’ll be lucky to be making sandwiches at a local deli or cleaning rooms at a Motel 6. Even a high school diploma can be a dead end, unless supplemented by the right kind of technical training. Get a college degree, however, and it is a different, happier, story.

Yes, some immigrant groups known for their obsessional devotion to their children’s educational attainment (Chinese and Vietnamese immigrants come to mind) still have a good shot at middle-class stability, even though the parents typically arrive in America with little skill or education and, working in low-wage occupations, add to poverty numbers in the short term. But researchers have followed several generations of Hispanics—again, by far the largest immigrant group—and what they’ve found is much less encouraging. Hispanic immigrants start off okay. Raised in the U.S., the second generation graduates high school and goes to college at higher rates than its parents, and it also earns more, though it continues to lag significantly behind native-born and other immigrant groups in these outcomes. Unfortunately, the third generation either stalls, or worse, takes what the Urban Institute calls a “U-turn.” Between the second and third generation, Hispanic high school dropout rates go up and college-going declines. The third generation is more often disconnected—that is, neither attending school nor employed. Its income declines; its health, including obesity levels, looks worse. Most disturbing, as we look to the future, a third-generation Hispanic is more likely to be born to a single mother than were his first- or second-generation predecessors. The children of single mothers not only have high poverty rates, regardless of ethnic or racial background; they’re also less likely to experience upward mobility, as a mountain of data shows.

The Hispanic “U-turn” probably has many causes. Like most parents these days, Hispanics say that they believe that education is essential for their children’s success. Cultural norms that prize family and tradition over achievement and independence often stand in the way. According to a study in the Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, Hispanic parents don’t talk and read to their young children as much as typical middle-class parents, who tend to applaud their children’s attempts at self-expression, do; differences in verbal ability show up as early as age two. Hispanic parents of low-achieving students, most of whom also voiced high academic hopes for their kids, were still “happy with their children’s test scores even when the children performed poorly.” Their children tended to be similarly satisfied. Unlike many other aspiring parents, Hispanics are more reluctant to see their children travel to magnet schools and to college. They also become parents at younger ages. Though Hispanic teen birthrates have fallen—as they have for all groups, apart from American Indians—they remain the highest in the nation.

The sheer size of the Hispanic population hinders the assimilation that might moderate some of these preferences. Immigrants have always moved into ethnic enclaves in the United States when they could, but schools and workplaces and street life inevitably meant mixing with other kinds, even when they couldn’t speak the same language. In many parts of the country, though, Hispanics are easily able to stick to their own. In fact, Generations of Exclusion, a longitudinal study of several generations of Mexican-Americans, found that a majority of fourth-generation Mexican-Americans live in Hispanic neighborhoods and marry other Hispanics.

Other affluent countries have lots of immigrants struggling to make it in a postindustrial economy. Those countries have lower child-poverty rates than we do—some much lower. But the background of the immigrants they accept is very different. Canada, New Zealand, and Australia are probably the best points of comparison. Like the United States, they are part of the Anglosphere and historically multicultural, with large numbers of foreign-born residents. However, unlike the U.S., they all use a points system that considers education levels and English ability, among other skills, to determine who gets immigration visas. The Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project calculates that, while 30 percent of American immigrants have a low level of education—meaning less than a high school diploma—and 35 percent have a college degree or higher, only 22 percent of Canadian immigrants lack a high school diploma, while more than 46 percent have gone to college. (Canada tightened its points system after a government study found that a rise in poverty and inequality during the 1980s and 1990s could be almost entirely attributed to an influx of poorer immigrants.) Australia and New Zealand also have a considerably more favorable ratio of college-educated immigrants than does the United States. The same goes for the U.K.

The immigration ecosystem of the famously egalitarian Nordic countries also differs from the U.S.’s in ways that have kept their poverty numbers low. Historically, the Nordics didn’t welcome large numbers of greenhorns. As of 1940, for instance, only 1 percent of Sweden’s population was foreign-born, compared with almost 8.8 percent of Americans. After World War II, Nordic immigration numbers began rising, with most of the newcomers arriving from developed countries, as was the case in the U.S. until 1965. In Finland and Iceland, for instance, the plurality of immigrants today is Swedish and Polish, respectively. In Norway, the majority of immigrants come from Poland and Lithuania. Note that these groups have low poverty rates in the U.S., too.

Sweden presents the most interesting case, since it has been the most welcoming of the Nordic countries—and it has one of the most generous welfare states, providing numerous benefits for its immigrants. For a long time, the large majority of Sweden’s immigrants were from Finland, a country with a similar culture and economy. By the 1990s, the immigrant population began to change, though, as refugees arrived from the former Yugoslavia, Iran, and Iraq—populations with little in common culturally with Sweden and far more likely to be unskilled than immigrants from the European Union. By 2011, Sweden, like other European countries, was seeing an explosion in the number of asylum applicants from Syria, Afghanistan, and Africa; in 2015 and 2016, there was another spike. Sweden’s percentage of foreign-born has swelled to 17 percent—higher than the approximately 13 percent in the United States.

How has Sweden handled its growing diversity? We don’t have much reliable data from the most recent surge, but numbers from earlier this decade suggest the limits of relying on copious state benefits to acclimate cultural outsiders. In the U.S., immigrants are still more likely to be employed than are the native-born. In Sweden, the opposite holds. More than 26 percent of Swedish newcomers have remained unemployed long-term (for more than a year). Immigrants tend to be poorer than natives and more likely to fall back into poverty if they do surmount it. In fact, Sweden has one of the highest poverty rates among immigrants relative to native-born in the European Union. Most strikingly, a majority of children living in Sweden classified as poor in 2010 were immigrants.

Despite its resolute antipoverty efforts, Sweden has, if anything, been less successful than the U.S. at bringing its second-generation immigrants up to speed. According to the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) survey, Sweden has “declined over the past decade [between 2005 and 2015] from around average to significantly below average . . . . No other country taking part in PISA has seen a steeper fall.” The Swedish Education Agency reports that immigrant kids were responsible for 85 percent of a decline in school performance.

Outcomes like these suggest that immigration optimists have underestimated the difficulty of integrating the less-educated from undeveloped countries, and their children, into advanced economies. A more honest accounting raises tough questions. Should the United States, as the Trump administration is proposing, and as is already the case in Canada and Australia, pursue a policy favoring higher-skilled immigration? Or do we accept higher levels of child poverty and lower social mobility as a cost of giving refuge and opportunity to people with none? If we accept such costs, does it even make sense to compare our child-poverty numbers with those of countries like Denmark or Sweden, which have only recently begun to take in large numbers of low-skilled immigrants?

Recent events in Denmark and Sweden put another question in stark relief. How many newcomers—especially from very different cultures—can a country successfully absorb, and on what timetable? A surge of asylum seekers beginning in 2015 forced both countries to introduce controls at their borders and limits to asylum acceptances. Their existing social services proved unable to cope with the swelling ranks of the needy; there was not enough housing, and, well, citizens weren’t always as welcoming as political leaders might have wished. The growing power of anti-immigrant political parties has shocked these legendarily tolerant cultures.

And yet one more question: How long can generous welfare policies survive large-scale low-skilled immigration? The beneficent Nordic countries are not the only ones that need to wonder. The National Academies of Sciences finds that immigration to America has an overall positive impact on the fiscal health of the federal government, but not so for the states and localities that must pay for education, libraries, some social services, and a good chunk of Medicaid. Fifty-five percent of California’s immigrant families use some kind of means-tested benefits; for natives, it’s 30 percent. The centrist Hamilton Project observes that high-immigrant states—California, New York, New Jersey, among others—“may be burdened with costs that will only be recouped over a number of years, or, if children move elsewhere within the United States, may never fully be recovered.”

In short, confronting honestly the question of child-poverty rates in the United States—and, increasingly, such rates in other advanced countries—means acknowledging the reality that a newcomer’s background plays a vital role in immigrant success. Alternatively, of course, one can always fall back on damning worries about our current immigration system as evidence of racism. Remember November 8, 2016, if you want to know how that will play out.

A young girl eats at a Salvation Army Thanksgiving dinner in Santa Ana, California. (ALLEN J. SCHABEN/LOS ANGELES TIMES/GETTY IMAGES)

Immigrant children from El Salvador and Guatemala who entered the country illegally board a bus after they were released from a family detention center in San Antonio, Texas on July 7, 2015. (Eric Gay / Associated Press)

Articles about America’s high levels of child poverty are a media evergreen. Here’s a typical entry, courtesy of the New York Times’s Eduardo Porter: “The percentage of children who are poor is more than three times as high in the United States as it is in Norway or the Netherlands. America has a larger proportion of poor children than Russia.” That’s right: Russia.

Outrageous as they seem, the assertions are true — at least in the sense that they line up with official statistics. Comparisons of the sort that Porter makes, though, should be accompanied by an asterisk pointing to a very American reality. Before Europe’s recent migration crisis, the United States was the only developed country to routinely import millions of very poor, low-skilled families, from some of the most destitute places on Earth — especially from undeveloped areas of Latin America — into its communities, schools and hospitals. Let’s just say that Russia doesn’t care to do this — and, until recently, Norway and the Netherlands didn’t, either.

Pundits prefer silence on the relationship between America’s immigration system and poverty, and it’s easy to see why. The subject pushes us into the sort of wrenching trade-offs that politicians and advocates prefer to avoid. Here’s the problem in a nutshell: You can allow mass low-skilled immigration, which many consider humane. But if you do, it becomes a lot harder to pursue the equally humane goal of reducing child poverty in this country.

::

In 1964, the federal government settled on a standard definition of poverty: an annual income less than three times the amount required to feed a family (size dependent) over that period of time. Back then, close to 23% of American kids were poor. Today, about 18% of kids are below the poverty line, amounting to 13,250,000 children.

A large majority of America’s poor immigrant children — and, at this point, a large fraction of all its poor children — are Latino.

At first, immigration did not affect child-poverty figures. The 1924 Immigration Act sharply reduced the number of immigrants from poorer Eastern European and southern countries, and it altogether banned Asians. The relatively small number of immigrants settling in the United States tended to be from affluent nations. According to the Migration Policy Institute, in 1970, immigrant children were less likely to be poor than were the children of native-born Americans.

By 1980, the situation had reversed: immigrant kids were now poorer than native-born ones. Why? The 1965 Immigration and Naturalization Act overturned the 1924 restrictions and made “family preference” a cornerstone of immigration policy. In consequence of that move, as well as large-scale illegal immigration, a growing number of new Americans hailed from less-developed countries. As of 1990, immigrant kids had poverty rates 50% higher than their native counterparts. At the turn of the millennium, more than one-fifth of immigrant children were classified as poor.

Perhaps the most uncomfortable truth about these statistics is that a large majority of America’s poor immigrant children — and, at this point, a large fraction of all its poor children — are Latino.

The United States started collecting separate poverty data on Latinos in 1972. That year, 22.8% of those originally from Spanish-language countries of Latin America were poor. The percentage hasn’t risen dramatically since then; it’s now at 25.6%. But because the Latino population in America quintupled during those years, these immigrants substantially expanded the nation’s poverty rolls. Latinos are now the largest U.S. immigrant group by far — and the lowest-skilled. Pew estimates that Latinos accounted for more than half the 22-million-person rise in the official poverty numbers between 1972 and 2012.

At the same time, then, that America’s War on Poverty was putting a spotlight on poor children, the immigration system was steadily making the problem worse. Between 1999 and 2008 alone, the United States added 1.8 million children to the poverty total; the Center for Immigration Studies reports that immigrants accounted for 45% of them.

Latino immigration is of course not the only reason that the United States has such troubling child-poverty rates. Other immigrant groups, such as North Africans and Laotians, add to the ranks of the under-18 poor. And even if we were following the immigration quotas set in 1924, the United States would be something of an outlier. Perhaps the nation’s biggest embarrassment is the alarming number of black children living in impoverished homes, about 3.7 million (compared to 5.1 million poor Latino kids).

But immigrant poverty belongs in a different category from black poverty. After all, immigrants voluntarily come to the United States, usually seeking opportunity. These days, they don’t always find it.

Yes, some immigrant groups known for their devotion to their children’s educational attainment (Chinese immigrants come to mind) have a good shot at middle-class stability, even if the parents arrive in America with little skill or education. Researchers, however, have followed several generations of Latinos — again, by far the largest immigrant group — and what they’ve discovered is not encouraging.

Latino immigrants start off OK. Raised in the United States, second-generation Latinos go to college at higher rates than their parents, and they also earn more. Unfortunately, the third generation either stalls or takes what the Urban Institute calls a “U-turn.” Between the second and third generation, Latino high school dropout rates go up and college-going declines. Third-generation Latinos are more often disconnected — that is, they neither attend school nor find employment.

::

Other affluent countries have lots of immigrants struggling to make it in a postindustrial economy. Those countries have lower child-poverty rates than we do — some much lower. But the background of the immigrants they accept is very different. Canada is probably the best comparison. Like the United States, it’s part of the Anglosphere and is historically multicultural. Unlike the United States, it uses a points system that considers education levels and English ability, among other skills, to determine who gets a visa. The Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project calculates that 30% of American immigrants have less than a high school diploma, while 35% have a college degree or higher. Only 22% of Canadian immigrants lack a high school diploma, while more than 46% have gone to college.

Sweden presents another illuminating case. For a long time, the large majority of Sweden’s immigrants were from Finland, a country with a similar culture and economy. By the 1990s, the immigrant population began to change as refugees arrived from the former Yugoslavia, Iran and Iraq — populations far more likely to be unskilled than immigrants from the European Union. By 2011, Sweden was seeing an explosion in the number of asylum applicants from Syria, Afghanistan and Africa; in 2015 and 2016, there was another spike. Sweden’s percentage of foreign-born has swelled to 17% — higher than the approximately 13% in the United States.

How has Sweden handled its growing diversity? Numbers from earlier this decade suggest that immigrants tend to be poorer than natives and more likely to fall back into poverty if they do surmount it. In fact, Sweden has one of the highest poverty rates among immigrants relative to native-born in the European Union. Most striking, a majority of children living in Sweden classified as poor in 2010 were immigrants.

Outcomes like these suggest that immigration optimists have underestimated the difficulty of integrating the less-educated from undeveloped countries, and their children, into advanced economies. A more honest accounting raises tough questions. Should the United States favor higher-skilled immigration? Or do we accept higher levels of child poverty and lower social mobility as a cost of giving opportunity to people with none? If we accept such costs, does it make sense to compare our child-poverty numbers with those of countries such as Sweden, which have only recently begun to take in large numbers of low-skilled immigrants?

Alternatively, we can fall back on shouting “racism” every time someone expresses concern about our immigration system. Remember Nov. 8, 2016, if you want to know how that will play out.

Kay S. Hymowitz is the William E. Simon Fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a contributing editor of City Journal, from which this essay was adapted.

More than 52 million Americans live in economically distressed communities

By Sandy English

28 September 2017

A new analysis of Census data shows that the so-called economic recovery under the Obama administration was an unmitigated catastrophe for the 20 percent of the American population that live in the poorest areas of the United States and that gains of jobs and income have gone overwhelming to the top 20 percent richest areas.

“The 2017 Distressed Communities Report,” published by the Economic Innovation Group (EIG), analyzes the census data for 2011-2015 for people living in each of the nearly 7,500 American zip codes according to several criteria.

The EIG’s Distressed Communities Index (DCI) considers the percentage of the population without a high school diploma, the percentage of housing vacancies, the percentage of adults working, the percentage of the population in poverty, the median income ratio (the percentage of median income that a zip code has for its state), the change in employment from 2011 to 2015, and the change in the number of businesses in the same period.

The report divides the findings for zip codes into five quintiles based on these indicators, rated from worst- to best-performing: distressed, at risk, mid-tier, comfortable, and prosperous.

The results show that distressed communities—52.3 million people or 17 percent of the American population—experienced an average 6 percent drop in the number of adults working and a 6.3 percent average drop in the number of business establishments.

“Far from achieving even anemic growth from 2011 to 2015,” the report notes, “distressed communities instead experienced what amounts to a deep ongoing recession.”

Further, “fully one third of the approximately 44 million Americans receiving SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or food stamps) and other cash public assistance benefits (such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)) live in distressed communities.” The report notes that most distressed communities have seen zero net job growth since 2000.

Residents in these zip codes are five times more likely to die than those in prosperous zip codes. Deaths from cancer, pregnancy complications, suicide, and violence are even higher. “Mental and substance abuse disorders are 64 percent higher in distressed counties than prosperous ones, with major clusters in Appalachia and Native American communities where rates exceed four or five times the national average,” the report continues.

One other important and alarming fact which the report highlights is that over a third of the distressed zip codes contain so-called “brownfield” sites—areas which are polluted or contaminated in some way. Not only do these have impacts on real estate and business development, they present a whole array of health hazards to the very poorest Americans.

Distressed communities can be found all over the United States but are concentrated in the South: 43 percent of Mississippi’s zip codes are distressed, followed by Alabama, West Virginia, Arkansas and Louisiana. According to the report, [the South] “is home to a staggering 52 percent of all Americans living in distressed zip codes—far above its 37.5 percent share of the country’s total population.”

After this, the Southwest and Great Lakes region have the largest share. In the Northeast, most distressed communities tend to be found in urban areas and in the South, primarily in rural areas.

The biggest cities with the largest numbers of distressed zip codes are Cleveland, Ohio, Newark, New Jersey, Buffalo, New York, Detroit, Michigan and Toledo, Ohio. Mid-sized cities with the highest number of distressed zip codes include Youngstown, Ohio, Trenton, New Jersey, Camden, New Jersey, Gary, Indiana, Hartford, Connecticut and Flint, Michigan.

Urban counties with the highest number of distressed zip codes include Cook County in Illinois, with Chicago at its center, Los Angeles County in California, Harris County in Texas, with Houston at its center, and Wayne County in Michigan, encompassing Detroit. Most of these urban areas were once industrial centers and home to the industrial working class.

Distressed zip codes that have a majority of minorities living in them are more than twice as likely to be distressed as zip codes that are majority white. “In total,” the report notes, “45 percent of the country’s majority-minority zip codes are distressed and only 7 percent of them are prosperous.” At the same time there are numerous distressed communities that are almost completely white. A quarter of the total distressed population is under 18.

The report found that the economic benefits of the recovery after the 2008 recessions have gone to the top quintile of zip codes, where the wealthier layers of the population live, including not only the very rich but also the upper middle class.

These areas, which the DCI terms prosperous, and make up roughly 85 million Americans or 27 percent of the US population, have for the most part the economic wherewithal to finance higher levels of education, have the lowest housing vacancy, highest percentage of working adults, and have had the lion’s share of job and business expansion.

“The job growth rate in the top quintile was 2.6 times higher than nationally from 2011 to 2015, and business establishments proliferated three times faster than they did at the national level,” the report notes. “Prosperous zip codes stand worlds apart from their distressed counterparts, seemingly insulated from many of the challenges with which other communities must grapple. The poverty rate is more than 20 points lower in the average prosperous community than it is in the average distressed one.”

The report makes much less of an analysis of the other three, middle quintiles, the at risk, mid-tier, and comfortable categories, but it does note some trends that address the overall trends nation-wide. “A remarkably small proportion of places fuel national increases in jobs and businesses in today’s economy. High growth in these local economic powerhouses buoys national numbers while obscuring stagnant or declining economic activity in other parts of the country.”

One of the more telling aspects of the report is that extreme poverty in the US is presided over by both capitalist parties: Democratic and Republic politicians have equal numbers of distressed communities in their constituencies. Democrats, in fact, “represent six of the 10 most distressed congressional districts.”

Another observation from the voting data, and one of the few that looks at conditions beyond the bottom and top quintiles, is worth quoting in full:

“President Trump accumulated a 3.5 million vote lead in counties that fell into the bottom three quintiles of well-being (equivalent to 9.4 percent of all votes cast in these counties). A vast array of factors determined voting patterns in the 2016 election, but it stands that the ‘continuity’ candidate performed better in the places benefiting most from the status quo, while the ‘change’ candidate performed better in the places one would expect to find more dissatisfaction.”

Broader figures and the historical view of wealth distribution in the US—that one percent of the population control 40 percent of the wealth or the decades-long decline in the percentage of the national income that goes to the working class—is not brought out in the report but the data add to a complete picture of social conditions across the United States, the character and geographical distribution of social and economic conditions in a country of more than 320 million.

The portrait provided by the EIG report is not simply one of increasing misery and poverty for the bottom 20 percent, and not only one in which only a minority of Americans are achieving anything like “prosperity,” but of growing and explosive dissent among tens of millions.

It exposes as a bold-faced lie the claim that President Obama made at the end of his second term, that “things have never been better” in America.

September 20, 2017

The Awful Future that Looms for a Majority of Today’s Americans

When it comes to the future, an overwhelming majority of Americans have adopted a mindset that is a variation of Isiah 22:12: “Let us eat, drink and be merry for tomorrow does not matter.” Recently, federal debt surpassed the $20 Trillion mark (additional state and local debt amount to another $2.9 Trillion). That milestone was greeted by the Ruling Class and a vast preponderance of the citizenry with a yawn and a shrug of the shoulder. As the ongoing determination to promote new entitlement spending and the refusal to rein in, but instead to expand, existing programs continues unabated.

Any attempt to seriously discuss the financial fate of the nation is ignored and dismissed with the proviso that its someone else’s problem for another day down the road. In reality, this dilemma is not someone else’s problem. The average life expectancy in the United States today is 79. That means that over 225 million citizens and non-citizens in the country today will still be alive in 30 years.

And what will this nation be facing 30 years hence? Recently, the Government Accountability Office as well as a number of experts such as Price Waterhouse have projected what that scenario will be if the country remains on its present course (with no new entitlements such as single payer health care and government mandated and paid maternity leave.) Note: All dollar amounts are in 2017 Dollars.

A.  Federal, State and local government spending currently amounts to $7 Trillion per year or 37% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). By 2048 these entities combined will be spending in excess of $17 Trillion per year, or over 50% of GDP. As interest costs on the overall debt will increase from $0.4 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, healthcare spending (includes Obamacare subsidies) will vault from $1.6 Trillion to $3.7 Trillion, Social Security and pension payments will grow from $1.4 Trillion to $3.5 Trillion, education spending from $1 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, and welfare programs from $0.5 Trillion to $1.3 Trillion.

Federal, State and local government spending currently amounts to $7 Trillion per year or 37% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). By 2048 these entities combined will be spending in excess of $17 Trillion per year, or over 50% of GDP. As interest costs on the overall debt will increase from $0.4 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, healthcare spending (includes Obamacare subsidies) will vault from $1.6 Trillion to $3.7 Trillion, Social Security and pension payments will grow from $1.4 Trillion to $3.5 Trillion, education spending from $1 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, and welfare programs from $0.5 Trillion to $1.3 Trillion.

Federal, State and local government spending currently amounts to $7 Trillion per year or 37% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). By 2048 these entities combined will be spending in excess of $17 Trillion per year, or over 50% of GDP. As interest costs on the overall debt will increase from $0.4 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, healthcare spending (includes Obamacare subsidies) will vault from $1.6 Trillion to $3.7 Trillion, Social Security and pension payments will grow from $1.4 Trillion to $3.5 Trillion, education spending from $1 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, and welfare programs from $0.5 Trillion to $1.3 Trillion.

Federal, State and local government spending currently amounts to $7 Trillion per year or 37% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). By 2048 these entities combined will be spending in excess of $17 Trillion per year, or over 50% of GDP. As interest costs on the overall debt will increase from $0.4 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, healthcare spending (includes Obamacare subsidies) will vault from $1.6 Trillion to $3.7 Trillion, Social Security and pension payments will grow from $1.4 Trillion to $3.5 Trillion, education spending from $1 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, and welfare programs from $0.5 Trillion to $1.3 Trillion.

B. The dramatic increase in spending and borrowing combined with the inevitable necessity of increased tax rates will crowd out private and public investment thereby slowing the growth of productivity, worker’s wages and the GDP. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that by 2040 the average annual real income per person will fall by $6,000.00. Thus, by 2048 the GDP of the United States will lag significantly behind China and India, as it falls to third place among the nations of the world. The U.S. GDP will increase only 76% by 2048 while government spending increases by 142%.

C. Concurrent with and because of the spending, stagnant growth and reduced personal income, the overall government debt will increase significantly as tax proceeds (despite eventual higher rates) will not generate anything close to the revenue necessary to offset spending, as tax revenues to the Federal, State and local governments will not exceed 30% of the GDP, whereas spending will absorb 51% of the GDP. By 2048 the overall government debt (Federal, State and local may well exceed $68 Trillion as compared to $23 Trillion today. Thus, the interest costs will increase fivefold, as not only does the debt swell, but the United States will have to appeal to lenders willing to underwrite a nearly bankrupt nation. Today this country, with 5% of the world’s population, accounts for over 32% of Global debt, but by 2048 it will account for 49% of Global debt. In essence, America will be at the mercy of the rest of the world and a second-tier economy.

D. Over the next 30 years there will be inevitable recessions, global financial crises and international military encounters. The United States will, with this level of debt and spending, find itself in an increasingly precarious position, as it may not be able to successfully weather any serious economic downturn or global conflict.

E. The above statistics do not include the current Democratic Party’s love affair with single-payer healthcare or “Medicare for all.” If that program were included, the annual government expenditures in 2048 (over and above current healthcare spending and interest costs) would balloon from $17 Trillion to $20 Trillion (60% of annual GDP) (and the debt would grow from $68 Trillion to over $86 Trillion.

The tsunami that will inundate this nation is inevitable as there is no willingness, regardless of party, to confront these issues.

The Democrats and their mind-numbed followers, now fully wedded to socialism, have convinced each other, and unfortunately much of the citizenry, that there is a bottomless pit of money to be siphoned from the so-called rich and the golden goose that is Capitalism, the engine of the nation’s GDP, will continue in perpetuity to lay the gold eggs regardless of any abuse or restraint. The one-time confiscation of the wealth of all the billionaires in the U.S. would amount to $2.2 Trillion (less than 31% of all government spending in 2017). Further, Capitalism cannot thrive without capital and profit, both of which the Democrats would severely restrict and control, thus, exacerbating the scenario outlined above.

The Republicans, while cognizant of the dire future ahead, prefer to hide their heads in the sand and defer matters to another day and another Congress and another President, as they are fearful of telling the people the truth and risk losing political power. Thus, their pre-determined inability and lack of fortitude in addressing Obamacare or any long-term spending programs.

Donald Trump continues to tout new programs (such as paid maternity leave), adamantly refuses to address the out of control entitlement spending, and is content with modified single-payer health care. He claims that economic growth will take care of all the problems; however, unless he and his successors find a way to grow the economy at an annual 5-7% per year for the next 20 to 30 years, that platitude is meaningless (the highest ten-year period of GDP growth -- 6.7% -- in the past 100 years took place in 1939-1948, which included massive war production for World War II). President Trump, has no plan or desire to mitigate the disaster looming on the horizon preferring to kick the can down the road while mouthing the usual banalities about reining in spending.

Thus, the populace, instead of being aware of the disaster ahead, is taking its lead from the Ruling Class. Alternatively, the American people are blithely swimming in a sea of banalities and faux causes. Whether it is promoting transgenderism, drowning in cults of personality, defacing and tearing down statues, feverously looking for supposed racism under every rock, asserting hypothetical compassion in the promotion of open borders and amnesty for untold millions, breathlessly endorsing the false God of climate change, cheering for their side of the political spectrum to humiliate the other, or demanding that government make their lives better.

I will not be among the 225 million Americans living today that will be alive in 2048. I have been fortunate to live throughout the golden age of America’s power and influence, but regrettably to also see the impending end of this glorious and short-lived era. The true tragedy is that those 225 million refuse to understand that for them there is no tomorrow to disregard.

When it comes to the future, an overwhelming majority of Americans have adopted a mindset that is a variation of Isiah 22:12: “Let us eat, drink and be merry for tomorrow does not matter.” Recently, federal debt surpassed the $20 Trillion mark (additional state and local debt amount to another $2.9 Trillion). That milestone was greeted by the Ruling Class and a vast preponderance of the citizenry with a yawn and a shrug of the shoulder. As the ongoing determination to promote new entitlement spending and the refusal to rein in, but instead to expand, existing programs continues unabated.

Any attempt to seriously discuss the financial fate of the nation is ignored and dismissed with the proviso that its someone else’s problem for another day down the road. In reality, this dilemma is not someone else’s problem. The average life expectancy in the United States today is 79. That means that over 225 million citizens and non-citizens in the country today will still be alive in 30 years.

And what will this nation be facing 30 years hence? Recently, the Government Accountability Office as well as a number of experts such as Price Waterhouse have projected what that scenario will be if the country remains on its present course (with no new entitlements such as single payer health care and government mandated and paid maternity leave.) Note: All dollar amounts are in 2017 Dollars.

A.  Federal, State and local government spending currently amounts to $7 Trillion per year or 37% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). By 2048 these entities combined will be spending in excess of $17 Trillion per year, or over 50% of GDP. As interest costs on the overall debt will increase from $0.4 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, healthcare spending (includes Obamacare subsidies) will vault from $1.6 Trillion to $3.7 Trillion, Social Security and pension payments will grow from $1.4 Trillion to $3.5 Trillion, education spending from $1 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, and welfare programs from $0.5 Trillion to $1.3 Trillion.

Federal, State and local government spending currently amounts to $7 Trillion per year or 37% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). By 2048 these entities combined will be spending in excess of $17 Trillion per year, or over 50% of GDP. As interest costs on the overall debt will increase from $0.4 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, healthcare spending (includes Obamacare subsidies) will vault from $1.6 Trillion to $3.7 Trillion, Social Security and pension payments will grow from $1.4 Trillion to $3.5 Trillion, education spending from $1 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, and welfare programs from $0.5 Trillion to $1.3 Trillion.

Federal, State and local government spending currently amounts to $7 Trillion per year or 37% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). By 2048 these entities combined will be spending in excess of $17 Trillion per year, or over 50% of GDP. As interest costs on the overall debt will increase from $0.4 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, healthcare spending (includes Obamacare subsidies) will vault from $1.6 Trillion to $3.7 Trillion, Social Security and pension payments will grow from $1.4 Trillion to $3.5 Trillion, education spending from $1 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, and welfare programs from $0.5 Trillion to $1.3 Trillion.

Federal, State and local government spending currently amounts to $7 Trillion per year or 37% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). By 2048 these entities combined will be spending in excess of $17 Trillion per year, or over 50% of GDP. As interest costs on the overall debt will increase from $0.4 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, healthcare spending (includes Obamacare subsidies) will vault from $1.6 Trillion to $3.7 Trillion, Social Security and pension payments will grow from $1.4 Trillion to $3.5 Trillion, education spending from $1 Trillion to $2.4 Trillion, and welfare programs from $0.5 Trillion to $1.3 Trillion.

B. The dramatic increase in spending and borrowing combined with the inevitable necessity of increased tax rates will crowd out private and public investment thereby slowing the growth of productivity, worker’s wages and the GDP. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that by 2040 the average annual real income per person will fall by $6,000.00. Thus, by 2048 the GDP of the United States will lag significantly behind China and India, as it falls to third place among the nations of the world. The U.S. GDP will increase only 76% by 2048 while government spending increases by 142%.

C. Concurrent with and because of the spending, stagnant growth and reduced personal income, the overall government debt will increase significantly as tax proceeds (despite eventual higher rates) will not generate anything close to the revenue necessary to offset spending, as tax revenues to the Federal, State and local governments will not exceed 30% of the GDP, whereas spending will absorb 51% of the GDP. By 2048 the overall government debt (Federal, State and local may well exceed $68 Trillion as compared to $23 Trillion today. Thus, the interest costs will increase fivefold, as not only does the debt swell, but the United States will have to appeal to lenders willing to underwrite a nearly bankrupt nation. Today this country, with 5% of the world’s population, accounts for over 32% of Global debt, but by 2048 it will account for 49% of Global debt. In essence, America will be at the mercy of the rest of the world and a second-tier economy.

D. Over the next 30 years there will be inevitable recessions, global financial crises and international military encounters. The United States will, with this level of debt and spending, find itself in an increasingly precarious position, as it may not be able to successfully weather any serious economic downturn or global conflict.

E. The above statistics do not include the current Democratic Party’s love affair with single-payer healthcare or “Medicare for all.” If that program were included, the annual government expenditures in 2048 (over and above current healthcare spending and interest costs) would balloon from $17 Trillion to $20 Trillion (60% of annual GDP) (and the debt would grow from $68 Trillion to over $86 Trillion.

The tsunami that will inundate this nation is inevitable as there is no willingness, regardless of party, to confront these issues.

The Democrats and their mind-numbed followers, now fully wedded to socialism, have convinced each other, and unfortunately much of the citizenry, that there is a bottomless pit of money to be siphoned from the so-called rich and the golden goose that is Capitalism, the engine of the nation’s GDP, will continue in perpetuity to lay the gold eggs regardless of any abuse or restraint. The one-time confiscation of the wealth of all the billionaires in the U.S. would amount to $2.2 Trillion (less than 31% of all government spending in 2017). Further, Capitalism cannot thrive without capital and profit, both of which the Democrats would severely restrict and control, thus, exacerbating the scenario outlined above.

The Republicans, while cognizant of the dire future ahead, prefer to hide their heads in the sand and defer matters to another day and another Congress and another President, as they are fearful of telling the people the truth and risk losing political power. Thus, their pre-determined inability and lack of fortitude in addressing Obamacare or any long-term spending programs.

Donald Trump continues to tout new programs (such as paid maternity leave), adamantly refuses to address the out of control entitlement spending, and is content with modified single-payer health care. He claims that economic growth will take care of all the problems; however, unless he and his successors find a way to grow the economy at an annual 5-7% per year for the next 20 to 30 years, that platitude is meaningless (the highest ten-year period of GDP growth -- 6.7% -- in the past 100 years took place in 1939-1948, which included massive war production for World War II). President Trump, has no plan or desire to mitigate the disaster looming on the horizon preferring to kick the can down the road while mouthing the usual banalities about reining in spending.

Thus, the populace, instead of being aware of the disaster ahead, is taking its lead from the Ruling Class. Alternatively, the American people are blithely swimming in a sea of banalities and faux causes. Whether it is promoting transgenderism, drowning in cults of personality, defacing and tearing down statues, feverously looking for supposed racism under every rock, asserting hypothetical compassion in the promotion of open borders and amnesty for untold millions, breathlessly endorsing the false God of climate change, cheering for their side of the political spectrum to humiliate the other, or demanding that government make their lives better.

I will not be among the 225 million Americans living today that will be alive in 2048. I have been fortunate to live throughout the golden age of America’s power and influence, but regrettably to also see the impending end of this glorious and short-lived era. The true tragedy is that those 225 million refuse to understand that for them there is no tomorrow to disregard.

Read more: http://www.americanthinker.com/articles/2017/09/the_awful_future_that_looms_for_a_majority_of_todays_americans_.html#ixzz4tEUApC4L

Follow us: @AmericanThinker on Twitter | AmericanThinker on Facebook

Rural New York schools grapple with declining population, increasing poverty

By Jason Melanovski

20 September 2017

A recent report has highlighted the dire development of increasing poverty and declining enrollment many rural school districts are facing across New York state, forcing these districts to choose between making onerous cuts, combining with other districts, or closing schools within the district, thus forcing students to travel longer distances.

According to a report titled “Demographic Challenges Facing Rural Schools: Declining Enrollment and Growing Poverty” by the New York State Association of School Business Officials, the dual phenomena of increased poverty and lower enrollment are wreaking havoc on local school budgets, which are primarily funded by local property taxes.

Calling enrollment declines “omnipresent,” the report states that “96.7 percent of rural school districts had declining enrollment and 84.9 percent had drops of at least ten percent.”

While the rate and overall population in poverty is still higher in New York’s suburban and urban school districts, the poverty rate in rural areas is increasing at a noticeably faster pace.

From 2003 to 2015, the poverty rate for school-age children increased from 14 percent to 18 percent for children in rural school districts and from 19 percent to 21 percent for children in non-rural school districts. For both rural and non-rural school districts the greatest jump in poverty rates occurred between 2009 and 2011 following the 2008 financial crisis.

Another measure of the economic plight of school children is the percentage of children receiving free or reduced priced lunches. In rural school districts 48.3 percent of students receive free or reduced priced lunches, and that number rises to 53.2 percent of students in non-rural districts. A student is eligible for free or reduced priced lunch when his or her family makes less than 185 percent of the poverty level.

Although the report was released to shed light on the challenges facing rural school districts, it made clear that poverty among the state’s school children has no geographic limits. According the report, “The combination of poverty and Free- and Reduced-Price Lunch (FRPL) data show that a little more than one in every five schoolchildren in New York lives in poverty, while a little more than half of all school children face significant economic constraints at home.”

The report compiled data from the 340 rural school districts, which make up about half of those in New York State, but serve only a little more than 11 percent of the students.

The report noted that the population losses and increases in poverty cannot be separated from the financial crisis of 2008, stating “for a few years prior to the onset of the Great Recession, growth rates in urban and rural counties were closely related. Beginning in 2008, rural populations entered a period of sustained decline, while urban populations continued to grow, though their pace of growth slowed after 2011.”

According to United States Census data, the emptying of much of rural America can be directly connected to the shrinking number of jobs in non-metro areas, as the rural job market is now 4.26 percent smaller than it was in 2008.

Speaking to the Daily Star of Oneonta, NY, the rural Delaware Academy School District’s Superintendent Jason Thomson stated that the current 47 percent of students who qualify for free or reduced price meals is the “highest we’ve ever seen.”

In addition, many of the rural counties mentioned in the report have also been hit hard by the opioid epidemic, claiming the lives of young workers and reducing an already declining population. Tioga County, for instance, lost up to 10 percent of its population between 2002 and 2016 and averaged 16.7 opioid deaths from 2013 to 2015 according to New York state.

With rapidly declining enrollment, rural schools are forced to count on smaller and smaller budgets with each succeeding school year, resulting in cuts to classes, teachers, programs and extracurricular activities and an overall sense of living in a world with scant opportunities for future life.

As the report states, rural “schools may have to cut back on valuable academic and enrichment opportunities, from Advanced Placement courses to music and sports programs, when they no longer have the student numbers needed for viability. Any potential reductions in college readiness preparation are incredibly serious. Decreasing enrollment can also increase students’ sense of isolation as there are literally fewer peers for them to interact with.”

To add to an already dire state of morale in rural schools, despite the fact that poor rural schools often have significantly higher graduation rates than poor urban schools, diplomas from rural schools are often seen as “worthless” according to David Little, executive director of the New York State Rural Schools Association. Poor rural schools in New York are simply unable to afford the cost of offering advanced placement (AP) and college-level coursework that is seen as necessary by college admissions officers.

For its part, the New York state government and the Andrew Cuomo administration have failed to respond to the demographic and social declines in rural school districts and increase state aid. The state continues to use a formula created in 2008, prior to the financial crisis, which categorizes the majority of rural schools as “average need.” If current demographic and poverty data were used, the majority of rural schools would now be considered “high-need,” requiring increased state aid.

Increasing rural poverty is not unique to New York. It has been rising across the country after falling sharply over many decades to a record low rate in 2000 of 13.4 percent. 16.7 percent of rural Americans lived in poverty in 2015, compared to 13 percent in poverty within metropolitan areas, according to the United States Census Bureau.

By Eric London

15 September 2017

US Census data from 2016 released on Tuesday shows increasing social inequality amid a small gain in household income that is offset by a massive growth of personal debt and rising living costs.

The data tracks the ongoing redistribution of wealth from the working class to the wealthy as a result of the pro-Wall Street policies of both the Republican and Democratic parties. It substantiates the oligarchic character of the United States.

Social inequality

The Gini index, used to measure social inequality, with higher figures indicating a wider economic divide, rose slightly from 2015 (.479) to 2016 (.481). The 2016 figure, according to rankings in the CIA World Factbook, makes the US slightly more equal than Madagascar and less equal than Mexico.

In terms of aggregate income share, the shift from 2015 to 2016 is as follows:

The growth in inequality is even starker when traced from 2007, the year before the Wall Street crisis.

The data reflects income and not wealth, thereby providing an incomplete and conservative indication of the scale of inequality. Even within the highest quintile, the income share increased only for the top 10 percent, and, in particular, the top 5 percent.

Household income

The corporate media has portrayed the report as a sign of positive income growth, since it shows a slight rise in median income of 3.2 percent from 2015 to 2016.

But according to the Census data, the earnings of “full-time, year-round workers” remained stagnant. For men in this category, a total of 63.9 million people, earnings declined by 0.4 percent, from $51,859 in 2015 to $51,640 in 2016. For women in this category, 47.2 million people, there was a minor increase, 0.7 percent, from $41,257 in 2015 to $41,554 in 2016. In other words, families with 2 adults working full-time saw a paltry $78 increase in their yearly earnings from 2015 to 2016.

Claims of rising incomes mask the growth of inequality. The Census data shows that the household income of the 90th percentile (the 100th being the highest) was 12.53 times higher than the household income of the 10th percentile in 2016, up from 12.23 times higher in 2015 and 11.18 times higher in 2007. The degree to which income is concentrated in the richest 10 percent of the population is exemplified by the fact that the 5th percentile boasted a household income 3.82 times higher than the 50th percentile in 2016, up from 3.79 times in 2015 and 3.52 in 2007.

As Bloomberg News reported Wednesday, “Since 2007, average inflation-adjusted income has climbed more than 10 percent for households in the highest fifth of the earnings distribution, and it’s fallen 3.2 percent for the bottom quintile. Incomes of the top 5 percent jumped 12.8 percent over the period.”

For the working class, any income increase was transferred to the corporate elite in the form of rising debt payments and increasing living expenses, especially for health care.

According to figures from eHealth, a large private health exchange, average deductibles for families rose 5 percent from 2016 to 2017 (a year after the period covered by the Census report) and average individual premiums rose 22 percent over the same period.

The rising cost of student debt alone largely erases income increases seen by some young people. According to the Census, those aged 15 to 24 saw an income increase of 13.9 percent, from $36,564 in 2015 to $41,655 in 2016, while incomes for young people aged 25 to 34 rose 4.9 percent, from $58,091 to $60,932, nearly double the percentage increase for older age groups.

However, in 2016, student debt rose to an average of $30,000 per young person, up 4 percent from 2015, eliminating over 80 percent of the income rise for 25-34 year olds. For 15 to 24 year olds, the $4,000 increase in median income would hardly cover one sixth of the average debt payment, let alone make up for the fact that young people face a future in which they are unlikely to receive a pension, Social Security or Medicare.

Rising debt levels are not a phenomenon limited to young people. A Bloomberg report from August 10 notes that credit card defaults increased from the beginning of 2015—when roughly 2.5 percent of debt holders defaulted—to the end of 2016, when the total hit 3 percent. This figure subsequently climbed in 2017 to reach 3.49 percent.

Bloomberg notes: “After deleveraging in the aftermath of the last US recession, Americans have once again taken on record debt loads that risk holding back the world’s largest economy... Household debt outstanding--everything from mortgages to credit cards to car loans--reached $12.7 trillion in the first quarter [2017], surpassing the previous peak in 2008 before the effect of the housing market collapse took its toll, Federal Reserve Bank of New York data show.”

“For most Americans,” the report continues, “whose median household income, adjusted for inflation, is lower than it was at its peak in 1999, borrowing has been the answer to maintaining their standard of living. The increase in debt helps explain why the economy’s main source of fuel is providing less of a boost than in the past. Personal spending growth has averaged 2.4 percent since the recession ended in 2009, less than the 3 percent of the previous expansion and 4.3 percent from 1982-90.”