PAUL KRUGMAN

The disintegration of California,

a Mexican satellite welfare state of poverty, crime and high taxes

http://mexicanoccupation.blogspot.com/2013/04/paul-krugman-look-at-california-under.html

"Chairman of the DNC Keith Ellison was even

spotted wearing a

shirt stating, "I don't believe in borders" written in Spanish.

According to a new CBS news poll, 63

percent of Americans in competitive congressional districts think those

crossing illegally should be immediately deported or arrested. This

is undoubtedly contrary to the views expressed by the Democratic Party.

Their endgame is open borders, which has become evident over

the last eight years. Don't for one second let them convince you

otherwise." Evan Berryhill Twitter

@EvBerryhill.

OPEN BORDERS: IT’S ALL ABOUT KEEPING WAGES DEPRESSED!

"In the decade following the

financial crisis of 2007-2008, the capitalist class has delivered powerful

blows to the social position of the working class. As a result, the working class

in the US, the world’s “richest country,” faces levels of economic hardship not

seen since the 1930s."

"Inequality has reached unprecedented

levels: the wealth of America’s three richest people now equals the net

worth of the poorest half of the US population."

PELOSI,

FEINSTEIN, KAMALA HARRIS AND GAVIN NEWOMS’S MEXIFORNIA

Report:

California’s Middle-Class Wages Rise by 1 Percent in 40 Years

Justin

Sullivan/Getty Images

Middle-class wages in

progressive California have risen by 1 percent in the last 40 years, says a

study by the establishment California Budget and Policy Center.

“Earnings for California’s

workers at the low end and middle of the wage scale have generally declined or

stagnated for decades,” says the report, titled “California’s Workers Are

Increasingly Locked Out of the State’s Prosperity.” The report continued:

In

2018, the median hourly earnings for workers ages 25 to 64 was $21.79, just 1%

higher than in 1979, after adjusting for inflation ($21.50, in 2018 dollars)

(Figure 1). Inflation-adjusted hourly earnings for low-wage workers, those at

the 10th percentile, increased only slightly more, by 4%, from $10.71 in

1979 to $11.12 in 2018.

The report admits that the

state’s progressive economy is delivering more to investors and less to

wage-earners. “Since 2001, the share of state private-sector [annual new

income] that has gone to worker compensation has fallen by 5.6 percentage

points — from 52.9% to 47.3%.”

In 2016, California’s Gross

Domestic Product was $2.6 trillion, so the 5.6 percent drop shifted $146

billion away from wages. That is roughly $3,625 per person in 2016.

The report notes that wages

finally exceeded 1979 levels around 2017, and it splits the credit between the

Democrats’ minimum-wage boosts and President Donald Trump’s go-go economy.

The 40 years of flat wages are

partly hidden by a wave of new products and services. They include almost-free

entertainment and information on the Internet, cheap imported coffee in

supermarkets, and reliable, low-pollution autos in garages.

But the impact of California’s

flat wages is made worse by California’s rising housing costs, the report says,

even though it also ignores the rent-spiking impact of the establishment’s

pro-immigration policies:

In just the last decade

alone, the increase in the typical household’s rent far outpaced the rise in

the typical full-time worker’s annual earnings, suggesting that working

families and individuals are finding it increasingly difficult to make ends

meet. In fact, the basic cost of living in many parts of the state is more

than many single individuals or families can expect to earn, even if all adults

are working full-time

Specifically, inflation-adjusted

median household rent rose by 16% between 2006 and 2017, while

inflation-adjusted median annual earnings for individuals working at least 35

hours per week and 50 weeks per year rose by just 2%, according to a Budget

Center analysis of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey data.

Many workers are being paid

little more today than workers were in 1979 even as worker productivity has

risen. Fewer employees have access to retirement plans sponsored by their employers,

leaving individual workers on their own to stretch limited dollars and

resources to plan how they’ll spend their later years affording the high cost

of living and health care in California. And as union representation has

declined, most workers today cannot negotiate collectively for better working

conditions, higher pay, and benefits, such as retirement and health care, like

their parents and grandparents did. On top of all this, workers who take on

contingent and independent work (often referred to as “gig work”), which in

many cases appears to be motivated by the need to supplement their primary job

or fill gaps in their employment, are rarely granted the same rights and legal

protections as traditional employees.

The center’s report tries to blame

the four-decade stretch of flat wages on the declining clout of unions. But

unions’ decline was impacted by the bipartisan elites’ policy of mass-migration

and imposed diversity.

In

2018, Breitbart reported how Progressives for

Immigration Reform interviewed Blaine Taylor, a union carpenter, about the

economic impact of migration:

TAYLOR: If I hired a framer to do

a small addition [in 1988], his wage would have been $45 an hour. That was

the minimum for a framing contractor, a good carpenter. For a helper, it was

about $25 an hour, for a master who could run a complete job, it was about $45

an hour. That was the going wage for plumbers as well. His helpers typically

got $25 an hour.

Now, the average wage in Los

Angeles for construction workers is less than $11 an hour. They can’t go lower

than the minimum wage. And much of that, if they’re not being paid by the hour

at less than $11 an hour, they’re being paid per piece — per piece of plywood

that’s installed, per piece of drywall that’s installed. Now, the subcontractor

can circumvent paying them as an hourly wage and are now being paid by 1099,

which means that no taxes are being taken out. [Emphasis added]

Diversity

also damaged the unions by shredding California’s civic solidarity. In 2007,

the progressive Southern Poverty Law Center posted a report with the title

“Latino Gang Members in Southern California are Terrorizing and Killing

Blacks.” In the same year, an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times described another murder by Latino

gangs as “a manifestation of an increasingly common trend: Latino ethnic

cleansing of African Americans from multiracial neighborhoods.”

The center’s board members

include the executive director of the state’s SEIU union, a professor from the

Goldman School of Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley, and

the research director at the “Program for Environmental and Regional Equity” at

the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Outside

California, President Donald Trump’s low-immigration policies are pressuring

employers to raise Americans’ wages in a hot economy. The Wall Street Journal reportedAugust 29:

Overall, median weekly earnings

rose 5% from the fourth quarter of 2017 to the same quarter in 2018, according

to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. For workers between the ages of 25 and 34,

that increase was 7.6%.

Democrats Move Towards ‘Oligarchical Socialism,’ Says Forecaster Joel Kotkin

Associated Press

Left-wing

progressives are embracing a political alliance with Silicon Valley oligarchs

who would trap Americans in a cramped future without hope of upward

mobility for themselves or their children, says a left-wing political analyst

in California.

Historically, liberals advocated helping the middle class

achieve greater independence, notably by owning houses and starting companies.

But the tech oligarchy — the people who run the five most capitalized firms on

Wall Street — have a far less egalitarian vision. Greg Fehrenstein, who

interviewed 147 digital company founders, says most believe that “an

increasingly greater share of economic wealth will be generated by a smaller

slice of very talented or original people. Everyone else will increasingly

subsist on some combination of part-time entrepreneurial ’gig work‘ and

government aid.”

Numerous oligarchs — Mark Zuckerberg, Pierre Omidyar, founder of

eBay, Elon Musk and Sam Altman, founder of the Y Combinator — have embraced

this vision including a “guaranteed wage,” usually $500 or a $1,000 monthly.

Our new economic overlords are not typical anti-tax billionaires in the

traditional mode; they see government spending as a means of keeping the

populist pitchforks away. This may be the only politically sustainable way to

expand “the gig economy,” which grew to 7 million workers this year, 26 percent

above the year before.

Handouts, including housing subsidies, could guarantee for the

next generation a future not of owned houses, but rented small, modest

apartments. Unable to grow into property-owning adults, they will subsist while

playing with their phones, video games and virtual reality in what Google calls

“immersive computing.”

This plan, however, is being challenged by the return of

populism and nationalism when President Donald Trump defeated the GOP’s

corporatist candidates and the progressives’ candidate in 2016. In his 2017

inauguration, Trump declared:

For too long, a small group in our nation’s capital

has reaped the rewards of government while the people have borne the

cost. Washington flourished, but the people did not share in its wealth.

Politicians prospered, but the jobs left and the factories closed. The

establishment protected itself, but not the citizens of our country. Their

victories have not been your victories. Their triumphs have not been your

triumphs. And while they celebrated in our nation’s capital, there was little

to celebrate for struggling families all across our land.

That all changes starting right here and right now because this

moment is your moment, it belongs to you …

What truly matters is not which party controls our government,

but whether our government is controlled by the people.

For several years, Kotkin has been dissecting the Democrats’

shift from working-class politics toward a tacit alliance with the billionaires

in the new information-technology industries that are centralizing wealth and

power through the United States. In 2013, for example, he argued that

California’s politics were increasingly “feudal“:

As late as the 80s, California was democratic in a fundamental

sense, a place for outsiders and, increasingly, immigrants—roughly 60 percent

of the population was considered middle class. Now, instead of a land of

opportunity, California has become increasingly feudal. According to recent

census estimates, the state suffers some of the highest levels of inequality in the country. By some

estimates, the state’s level of inequality compares with that of such global models as the Dominican

Republic, Gambia, and the Republic of the Congo.

At the same time, the Golden State now suffers the highest level

of poverty in the country—23.5 percent compared to 16 percent nationally—worse

than long-term hard luck cases like Mississippi. It is also now home to

roughly one-third of the

nation’s welfare recipients, almost three times its proportion of the nation’s

population.

Like medieval serfs, increasing numbers of Californians are

downwardly mobile, and doing worse than their parents: native born Latinos

actually have shorter lifespans than their parents, according to one

recent report. Nor are things expected to get

better any time soon. According to a recent Hoover Institution survey, most Californians expect their

incomes to stagnate in the coming six months, a sense widely shared among the

young, whites, Latinos, females, and the less educated.

“Protecting

citizens from industrial capitalism’s giant corporations? Where were the

Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Reserve, the Office of Thrift

Supervision, and the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight as the

mortgage bubble blew up in 2008, nearly taking the whole financial system with

it and producing the worst economic bust since the Great Depression, which even

today has sunk the labor-force participation rate and hiked the suicide rate

among working-class men and women to record levels?”

Economist and Nobel-prize winner Paul Krugman speaks with journalists after meeting Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in Tokyo, Japan, on March 22, 2016. (Franck Robichon/AFP/Getty Images)

Krugman Admits He and Mainstream Economists Got Globalization Wrong

Paul Krugman, Nobel-prize winning economist and avowed champion of free trade, admits he and his colleagues got a few things seriously wrong about globalization, in particular around its downside impact on local labor markets.

“We missed a crucial part of the story,” Krugman wrote in a Bloomberg article in October, referring to members of the so-called “1990s consensus,” mainstream economists who worshipped at the altar of free trade.

According to his article, the consensus economists failed to measure adequately and properly account for the impact of globalization on specific communities, some of which were disproportionately hit hard. This despite the fact that models predicted, and figures later showed, that free trade was a net gain in terms of both jobs and wages in the broader American economy. Generalized gain but localized pain.

“Opening to trade increases the size of the economic pie by a few percent and yet shrinks some slices by 10 or 20 or 30 percent,” said David Autor, an MIT economics professor who wrote a groundbreaking paper on the disruptive impact of integrating China into the global economy and whom Krugman cites in his article.

“The benefits, in general, will be small and diffuse and broadly shared,” Autor said in an interview for the Institute for Fiscal Studies. “So lower prices of consumer goods, more variety of goods, perhaps a faster rate of product innovation.”

“However, the individuals who are in the sectors that become directly exposed to competition, they’re almost necessarily going to shrink,” he continued. “Those impacts tend to stay localized. Instead of wages falling just a little bit for people who have manual-dextrous skills, we see big job losses for individuals at those plants. Then the whole communities that surround them kind of—I don’t want to say implode, but they go into something of a state of decay.”

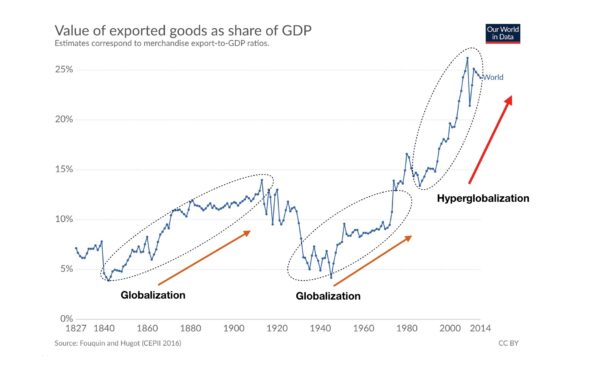

‘Hyperglobalization’

Aware of the pain of the working man and distressed by the backlash against globalization, Krugman, who now pens op-eds with tart titles like “The Roots of Regulation Rage,” is on a sojourn of shame.

Pit stops along the route include a February lecture in Australia headlined “What Did We Miss About Globalization?” and the October article mentioned above in Bloomberg titled “What Economists (Including Me) Got Wrong About Globalization.”

Those tuning in to Krugman’s proclamations of penitence will certainly hear mea culpa, but also caveats.

While admitting to errors, Krugman remains fundamentally pro-free trade and is loath to be seen as throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

“I frequently encounter people who have a story they’ve heard,” Krugman said in Australia. “They sorta kinda think they know what happened to economics. The story is ‘Well, economists used to think that trade is good for everybody and now they’ve learned that it actually has downsides and is much more problematic.’ It’s a good story, and it fits people’s desire to see the orthodoxy and the establishment receive its comeuppance. But it’s almost exactly wrong.”

The correct way to think about the issue, Krugman argues, is that the problem was less with globalization as with something far more nefarious that he calls “hyper globalization.”

Krugman says the out-sized downside impact of globalization-turned-hyper globalization is to regard the phenomenon as factors sparking a perfect storm.

The first factor: a paradigm shift of the international trading profile from “intra-industry trade among similar countries” to importing goods from countries with a massive labor-cost advantage.

The second factor was the acceleration of the process via technology, especially containerization. That coupled with an eager embrace of free trade by policymakers egged on by overconfident intellectuals who hadn’t thoroughly done their impact assessment homework.

Factor three, lack of policies in place to help people cope with massive displacement as entire industries disappeared, and whole communities were devastated.

“The hyper globalization is this changing environment that in some ways set the stage for the turmoil we’re now experiencing,” he explained during his lecture in Melbourne.

“Consensus economists didn’t turn much to analytic methods that focus on workers in particular industries and communities, which would have given a better picture of short-run trends,” Krugman wrote.

“This was, I now believe, a major mistake—one in which I shared a hand.”

Former labor secretary Richard Reich praised Krugman’s newfound humility, saying it’s high time the celebrated economist ate some crow.

“I’m glad he’s finally seen the light on trade,” Reich told Michael Hirsh of Foreign Policy.

“How rare is that?!” Autor echoed Reich’s praise of Krugman’s contrition.

‘The 1990s Consensus’

“It’s clear that the impact of developing-country exports grew much more between 1995 and 2010 than the 1990s consensus imagined possible,” Krugman wrote.

The consensus economists Krugman talks about posited in lockstep that when it comes to international trade, the freer the better.

This attitude is exemplified in his 1997 article in the Journal of Economic Literature, in which Krugman stated, “If economists ruled the world, there would be no need for a World Trade Organization. The economist’s case for free trade is essentially a unilateral case: a country serves its own interests by pursuing free trade regardless of what other countries may do.”

International trade redistributes incomes. It is a game with winners and losers, but—according to that consensus belief—the gains that accrue to the winners more than offset the losses borne by the losers. The idea is that the rising tide lifts all ships except for the least adaptive, which sink.

“This is a hugely good thing from a global perspective,” Krugman said at the Melbourne lecture, referring to the overall effects of free trade across the globe, “but not from the point of view of everybody.”

Low-skilled workers are hit hardest, and some stay down for the count.

In a 2005 college textbook on economics, Krugman and co-author Maurice Obstfeld wrote, “Owners of a country’s abundant factors gain from trade, but owners of a country’s scarce factors lose … [C]ompared with the rest of the world, the United States is abundantly endowed with highly skilled labor and … low-skilled labor is correspondingly scarce. Meaning international trade tends to make low-skilled workers in the United States worse off not just temporarily, but on a sustained basis.”

In his lecture, Krugman explains that bouts of globalization before “hyper globalization” were characterized by an exchange of similar goods between similar countries, with comparative advantage based on a range of factors, including specialized know-how and availability of primary inputs.

But the very nature of international trade underwent a sea change when low-labor cost countries like Bangladesh, China, and Mexico began to export manufactured goods to the West en masse.

‘China Shock’

David Autor’s paper “China Shock” (pdf) is widely hailed as having enlightened consensus economists to how egregiously disruptive aspects of globalization have been, both in terms of jobs lost and wages depressed.

Krugman, in his lecture, tipped his hat to Autor and quoted from “China Shock.”

“China Shock is a shorthand term for the very disruptive integration of China into Western trade,” Autor told the Institute for Fiscal Studies. “Specifically, in the context of the United States, it refers to China’s joining the World Trade Organization in 2001, and the surge of Chinese exports that this catalyzed. One way to see this is in 1991, about a quarter of one percent of all U.S. goods consumption was produced in China. By 2007, that was about 5 percent. So that’s a twenty-fold increase.”

Krugman said the explosion of trade between rich and emerging countries pulled down the wages of specific categories of workers.

“It’s clear that that kind of trade is a depressing factor on the wages of workers without lots of formal education,” Krugman said. “It’s just bad economics to deny that that’s a factor. The question has always been how important is it. And in the 1990s, many people, myself included, tried to estimate the impact of North-South trade on income distribution and came up with significant but modest numbers. Something like maybe a 3 percent decline in real wages of non-college educated workers caused by growth of international trade.”

Without specifying a number, he added that this figure later turned out to be higher, though not by much.

In regard to jobs lost, Krugman cited “China Shock,” saying that imports from China from the late 90s to the eve of the 2007 financial crisis, “displaced about a million jobs in the United States.”

He argued that over a million jobs were created over the same period, and the net effect on the economy in terms of employment was positive.

“No doubt a million jobs were created elsewhere,” Krugman said, “but they weren’t the same million jobs.”

“I keep on running into people who believe that economists think that free trade is good for everybody. That’s never been what models say. That’s never been what economic analysis says.”

He added that people in import-competing industries will be the hardest hit and that “if you have large imports of labor-intensive products, then workers without college degrees are likely to be hurt.”

“Growth in trade typically produces losers, perhaps substantial groups of losers.”

Autor said the pain to American communities from China-related trade came not just from slashed manufacturing jobs, but difficulty adapting and finding employment in different sectors.

“It turned out to have been much more disruptive than people had anticipated, both in terms of the amount of job loss in manufacturing; but also the difficulty people have had adjusting to that in terms of re-employment—in terms of re-employment and re-gaining jobs and prior earnings levels.”

Autor said when China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, “we saw very rapid decline in manufacturing in sectors in which China had rising comparative advantage, mostly labor-intensive production like shoes, textiles and other goods.”

He said workers who lost their jobs at the time not only were unable to find other work quickly, they “suffered sustained earnings losses.”

“In general, areas where manufacturing was going on, saw overall economic decline and malaise.”

While economists often resort to sterile-sounding terms like “disruption” and “malaise” to describe the impact on communities, it often takes politicians to give “hyper globalization” a human face.

‘American Carnage’

President Donald Trump, in his inaugural address, translated malaise into a searing buzzword.

“This American carnage stops right here and stops right now,” Trump said on July 20. “Mothers and children trapped in poverty in our inner cities; rusted-out factories scattered like tombstones across the landscape of our nation.”

Former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon, who had a hand in drafting Trump’s inaugural speech, used still another buzzword to refer to those Krugman labeled “losers.”

“It’s the Deplorables, who said ‘I don’t understand all this high finance, and I don’t understand all this mumbo jumbo, but here’s what I do understand,’” Bannon said in a speech at a meeting of the Committee on Clear and Present Danger. “The factories left, the jobs left with them, and the opioids came.”

“But the Deplorables found an instrument—Donald Trump. And that instrument,” Bannon argued, “in all its imperfections—is an armor-piecing shell.”

“We are one nation—and their pain is our pain,” Trump said at his inauguration. “Their dreams are our dreams, and their success will be our success. We share one heart, one home, and one glorious destiny.”

Steven Moore, a former White House pick for the Federal Reserve Board and author of “Trumponomics: Inside the America First Plan to Revive Our Economy,” told the Epoch Times of specific policy propositions that are meant to reforge the pain of those most hurt by hyper globalization into success.

‘Trumponomics’ Takes the Stage

“I believe we’re in a very abusive relationship with China right now,” Moore told The Epoch Times, adding that while the United States opened its market to China decades ago, China keeps its market closed.

He said Trump sought to correct that relationship by enacting a trade deal that would bring more balance. Still, China reneged on commitments made during the negotiations, and the process degenerated into tit-for-tat tariffs and, in effect, a trade war.

“I’m a free-trade guy,” Moore said, “I hate tariffs, I love free trade. But it’s hard to have free trade, frankly, with a country that is stealing, cheating, lying, involved in cyber-espionage against the United States, hacking into our computer systems.”

Moore called China “an increasingly menacing power,” and he hopes Trump’s policies will force them into a good and fair trading relationship with the United States.

“I do think China’s playing a dangerous game here. It’s going to hurt both of our countries,” Moore said, adding that consumers would be affected.

“China will be hit three or four times harder than we will, but it’s a mutually assured destruction strategy,” he said. “I do think Trump is using leverage. And I think at the end of the day, I’m actually fairly confident that Trump is going to get a victory here.”

Besides negotiating and renegotiating international trade deals, the domestic dimension of Trump’s policies has been to stimulate growth through tax cuts and deregulation.

Lawrence Kudlow, former financial analyst and current head of the National Economic Council under Trump, wrote in the foreword to Trumponomics that while he and the President don’t always see eye to eye, “Trump says we can get to 3, 4, or even 5 percent growth through tax reduction, deregulation, American energy production, and fairer trade deals, and he is exactly right.”

“He wanted tax cuts. He wanted to deregulate, he wanted to get the government out of the way,” is how Kudlow described Trump’s aims.

“What a contrast with the left—which was full of negativity,” Kudlow continued. “We can’t grow faster than 2 percent. We can’t get wages up. We have to live with secular stagnation. We can’t rebuild our coal industry. Climate change is going to bring the end of civilization. The inner cities cannot be hopeful and prosperous places again.”

‘The Case for Trump’

Historian Victor Davis Hanson wrote the book “The Case for Trump.” He echoes Kudlow’s perspective that, at the core of Trumponomics, are policies that seek to unlock the stifled potential of an under-performing U.S. economy.

Hanson told The Epoch Times that the results of Trump’s economic policies had defied the assumptions of naysayers.

“They said ‘the economy is stagnant: No 3 percent annualized GDP in ten years. No gain in real wages. They’ve written off the middle of the country. They’re losers. They’re not part of the globalized elite on the coast. They need to learn coding,” Hanson said of Obama-era policymakers and mainstream economists.

Trumponomics, Hanson said, accomplished “3 percent GDP, record-low unemployment, record-low minority unemployment, record energy production, the Iran deal is gone, those crazy Paris Accords finalized, Keystone, ANWAR.”

“Some of the best economic numbers our country has ever experienced are happening right now,” Trump tweeted earlier this month.

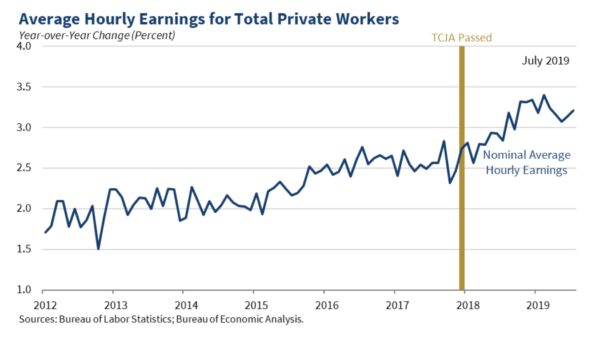

Wage growth is one of the standouts.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, from Sept. 2018 to Sept. 2019, real average hourly earnings increased 1.9 percent, seasonally

adjusted.

adjusted.

‘Economic Populist’

“Donald Trump is not an ideological conservative,” Moore explains in the book Trumponomics.

“Reagan was far more schooled in conservative thought and was more dedicated to the principles of limited government. Trump is for common sense. He is an economic populist in many ways—he believes in addressing the plight of ordinary people.”

“He’s authentic,” Hansen says of Trump. “He doesn’t play the game. If he goes to the Indiana State Fair, or he goes to Tulare, California, or the South, it’s the same Queens accent, same suit.”

“Hilary doesn’t do that,” Hansen says. “She’s got a Southern accent here and an inner-city accent here. John Kerry, when he ran, he had flannel at the State Fair. Trump is authentic; he is who he is. Unapologetic.”

“Hilary goes to West Virginia, and she says, ‘I’m sorry, you guys have to basically learn solar skills or something, I’m going to put you out of business.’

“Trump goes and says ‘I love big, beautiful coal.'”

No comments:

Post a Comment