“My facility has become extremely unsafe,” says Meghan King. She has been injured twice while working at Amazon’s GSP1 warehouse in Spartanburg, South Carolina.

Meghan King, working at a gas station

Meghan King, working at a gas station

In 2018, a fellow worker at her facility committed suicide. “She got pushed and bullied by management until she literally could not take it anymore,” Meghan says. The worker took paid time off, saying she needed time to cope with the stress. At home, she slit her wrists. Her body was discovered after she stopped answering her phone.

Meghan is one of a number of workers from GSP1 who contacted the World Socialist Web Site to expose the brutal work environment at the warehouse. They described dangerous conditions, psychological stress and the failure to provide compensation and treatment for injuries.

While shocking, their stories are common among Amazon warehouse workers throughout the country. In 2018, the World Socialist Web Site first published the story of Shannon Allen, a former Texas Amazon worker who became homeless after Amazon refused to pay for a workplace injury. After Shannon became widely known as an Amazon whistleblower, many other workers contacted the World Socialist Web Site to share their own stories about working at Amazon.

Meghan, 35, has worked on and off for the trillion-dollar multinational technology company since 2012. In 2017 and 2018, she worked as a security officer at the nearby BMW Spartanburg plant, which employs 8,800 workers. “That’s a country in and of itself,” she says. She is also licensed as a pharmacy technician. At Amazon, she served on the associate safety committee, where her role included trying to help other workers do their jobs safely.

Her first injury was in September of last year. Driving a pallet jack and racing to make rate, she turned her head suddenly to make sure an approaching vehicle would stop and felt a sharp pain in her neck.

“That happened at 7:20 a.m. and they made me wait until 2:30 p.m. to see a worker’s compensation doctor. They told me that if I left work I would not get paid. They forced me to stay at my job in pain.

“When I got there at 2:45, or whenever they let me see the doctor, I sat in the doctor’s office until almost 5:00.” The workers’ compensation doctor said she had strained a muscle in her neck and that there was nothing they could do for her. She ended up going to a private walk-in clinic later that evening, where she received treatment and medication. After just one day of rest, she went back to work on her next scheduled shift.

Meghan submitted a workers’ compensation claim, which would have covered her medications and treatment, but it was denied on the false grounds that she had not submitted the proper paperwork.

On December 18, she was injured a second time, slipping and falling on a wet floor in a bathroom. The floor had just been mopped but no wet floor sign had been put up. Two days later, she was diagnosed with a displaced coccyx and fractured sacrum.

Amazon again disputed the injury, first alleging that she was she was not working that day. When Meghan submitted proof that she was working on the day of the injury, Amazon announced that she must have been engaged in “horseplay” in the bathroom, ignoring witnesses who saw Meghan fall.

Today Meghan is on short-term disability. Every two weeks, she receives roughly $300, less than one-half of minimum wage. How does she get by? “I don’t. That does not even cover my car insurance.”

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) forms filed by Amazon for the Spartanburg warehouse indicate that there were 41 injuries at GSP1 in 2018, including 23 injuries serious enough to result in job transfers or restrictions. In 2019, there were 57 injuries, with 35 resulting in job transfers or restrictions.

Over a two year period, according to these forms, a total of 2,334 working days were lost on account of injuries, in addition to 3,516 days workers spent on job transfers or restrictions as a result of injuries.

While these figures are alarming in themselves, Meghan believes that these forms, which Amazon is required by law to submit to the federal authorities, understate the true number of injuries. She recalls the case of one worker who had been run over: “They fired the person driving the machine and the person who got run over.” However, she says, the name of the worker who had been run over does not appear on the OSHA forms filed by Amazon.

Anger and frustration about working conditions have mounting over a long period in the warehouse. Meghan says that many workers are “at the point of fed up.” In one recent incident, tensions flared over management insisting on blasting music over the loudspeakers in one area of the warehouse, making it difficult for workers to hear warning alarms or vehicles approaching.

It is not easy for workers to speak publicly about what happens inside Amazon warehouses. One worker who is currently working at GSP1 declined to be interviewed by the World Socialist Web Site, citing management threats that “speaking to the press” constitutes grounds for termination.

Another worker, identified in this article as “Alice,” agreed to be interviewed but did not want to use her real name out of fear of management retaliation. If Alice loses her job, she will not be able to pay her utility bill and her power will be shut off at home.

Alice was injured at Amazon over the summer of last year. She is concerned that publishing a description of exactly how she was injured would help management identify her. But she says she continued to work after the injury.

In this photo shared on social media, heavy objects perched precariously on high shelves at GSP1 pose a danger to workers.

In this photo shared on social media, heavy objects perched precariously on high shelves at GSP1 pose a danger to workers.

Her injury continues to cause her pain. “I’m having a hard time,” Alice says. She never received any medical care for the injury and never received any compensation.

“I go in there and I do my job to the best of my ability,” she says. “Some people get away with murder. You are taking a risk. It is so dangerous.”

Alice also describes Amcare, Amazon’s in-house medical care, as inadequate, a system in place for no reason other than to help Amazon deny injured workers’ claims. “You would think they would have to have licensed people in there to treat people,” Alice says. “It’s a very dangerous place to work.”

“Management needs to stop pushing us so hard,” Alice says. “They are pushing too hard, which is causing the injuries.”

“John,” who also requested to be identified by a pseudonym, is eager to discuss “the shithole that I have been trying to stay alive in for five years.”

John started out at Amazon working as a temp. Out of his temp group, which originally numbered from 20 to 40 workers, only 10 lasted through the first year. Now there are only two others left.

“Warehouse work is different,” John said. Younger workers do not realize that it is much more demanding work than bagging groceries or working at a gas station, he explains. Meanwhile, older workers are eventually exhausted. “It’s the burnout. It’s constantly fighting the bureaucracy above the warehouse, management inside warehouse. Constantly having this, that and the other taken away from you.”

He says that workers stay because they are “between a rock and a hard place.”

Workers think to themselves: “How much of this can I put up with? Pay and benefits are slightly better than other jobs. At what point does this go too far?” Many workers, he says, stay for the education assistance program, which workers view as a “ticket out of here.”

Like many Amazon workers the World Socialist Web Site has interviewed, John talks about psychological stress. “It affected me, too,” he says. Amazon has perfected a broad range of techniques designed to crank up the pressure on workers to work faster and harder without additional pay, which John describes as treating workers like “hamsters.”

John describes work-related stress as affecting his health and relationships. “There was a point in my life where it got into a spiraling pattern of destructive tendencies. I should probably have been dead about three times after working there. I was not handling the stress of working there very well.”

John explains that GSP1 workers make less than other warehouse workers who work in the area, such as at warehouses for Dollar General and Walmart. Amazon workers make $15.50 per hour. Meanwhile, he says, cashiers at the Chick-fil-A fast food chain start out at $17.00 per hour.

John confirms what many workers have told the WSWS about the so-called “raise” to $15 per hour at Amazon. This “raise” was accompanied by the elimination of variable compensation pay (VCP) and a stock vesting program. “I made $40,000 gross this past year. If you look at what I lost in VCP and lost in stock options, I got screwed.”

When asked about safety issues at the warehouse, John immediately interjects—“Roof leaks.”

“There was a point where it was difficult to drive PIT [powered industrial trucks],” he says. “They legit had big commercial trash cans that they were letting water drip into. There were dozens of plastic trash cans, each fifty gallons or so. It was hell to drive around those bins. They were all over the damn place.”

Asked about the loud music, John said: “That location is already loud, with the conveyors,” he says. “It’s metal on metal. You can’t hear the alarm anyway. You can’t tell if the alarm is going off unless the light is blinking. Unless you are looking at a 45-degree angle up” to see the alarm light, “it does not mean anything to you.”

John described workers as being incensed upon learning that they had been required to work through a bomb threat last summer. Workers should have been told, he says. Instead, Amazon kept them working, unaware of the danger. As it turns out, Alice was working during that shift. “That ticked me off,” she says. “They should have evacuated us.”

John also describes working through tornadoes. One tornado touched down “two miles down the interstate.” Workers could see “50 and 60 year old oaks swaying behind the warehouse.” A safety representative told them, “Oh don’t worry, it’s just wind shear.” After that, a bit of gallows humor: the ongoing joke about safety issues in the warehouse became: “Oh don’t worry, it’s just wind shear.”

Asked about injuries, John recalls one day walking into the warehouse and seeing around a dozen other workers walking by, each with plastic boots on one foot, indicating ankle injuries. John has a term for this all-too-common plastic-boot limp: “the Thriller shuffle,” after the Michael Jackson music video.

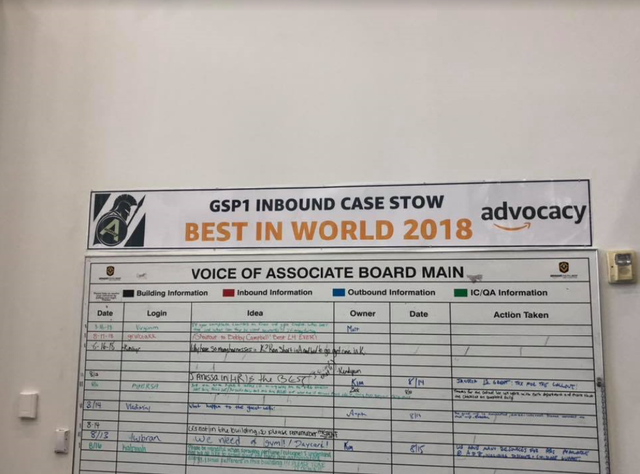

On the Voice of the Associate Board, workers can “voice our concerns to management,” Meghan says, “and we usually get a cookie cutter response and the issues still don’t usually get resolved at all.”

On the Voice of the Associate Board, workers can “voice our concerns to management,” Meghan says, “and we usually get a cookie cutter response and the issues still don’t usually get resolved at all.”

John tells a story of an older Amazon worker who had chronic emphysema and asthma. Many workers respected and looked up to him. When management would not listen, workers would go to him for advice.

One day, ten minutes before the end of the shift, the older worker told John that he could not breathe. When the worker arrived at the hospital, he was diagnosed with pneumonia in both lungs. He had been trying to make it until the end of the shift. “He kept on trucking,” John said. “He put himself far over what he could be expected to.”

After being treated, the older worker wanted to return to work at the warehouse. But he now needed to work with an oxygen tank, and management said they would not accommodate him. After paper-pushers gave him the run-around, management terminated his benefits. “The guy was out of work for almost a year.” He spiraled into depression and alcoholism. “That guy went through hell,” John says.

John was affected when he saw that the older worker, in desperate straits, had put up one of his prized possessions, an Apple watch, for sale online.

On social media, John has been encouraged by finding other Amazon workers who can relate to the experiences he has had. He calls this phenomenon, linking up with other Amazon workers on social media, the “Underground Railroad.”

Meghan spoke about the need for collective resistance by workers. “It’s like A Bug’s Life ,” Meghan says, referring to a 1998 computer-animated film that depicts a revolt of ants against larger, tyrannical insects. Individually, she says, workers are replaceable, but collectively: “We outnumber them.”

No comments:

Post a Comment