Senate Report: Biden Family Bought $100K of ‘Extravagant Items’ with China-Linked Credit Cards

Democrat presidential candidate Joe Biden’s family members bought more than $100,000 worth of “extravagant items” in 2017 using a line of credit linked to associates of the Chinese communist government.

A bombshell report by the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee and Senate Finance Committee details numerous cases in which Biden’s son, Hunter Biden, and family members have deep ties to the Chinese communist government, Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan.

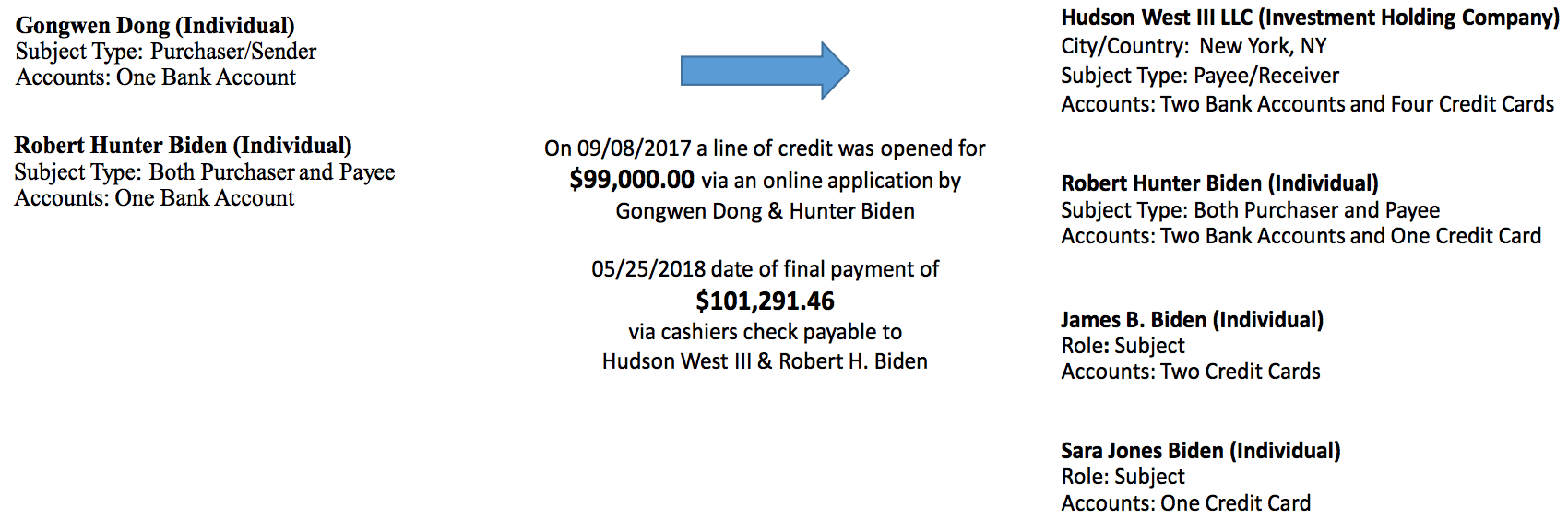

In one instance, the Senate report states that on September 8, 2017, Hunter Biden and Chinese national Gongwen Dong — with ties to the Chinese communist government — opened a bank account to fund a more than $100,000 “global spending spree” for members of the Biden family.

“Hunter Biden and Gongwen Dong, a Chinese national who has reportedly executed transactions for limited liability companies controlled by Ye Jianming, applied to a bank and opened a line of credit under the business name Hudson West III LLC (Hudson West III),” the Senate report states. The report continues:

Hunter Biden, James Biden, and James Biden’s wife, Sara Biden, were all authorized users of credit cards associated with the account. The Bidens subsequently used the credit cards they opened to purchase $101,291.46 worth of extravagant items, including airline tickets and multiple items at Apple Inc. stores, pharmacies, hotels, and restaurants. The cards were collateralized by transferring $99,000 from a Hudson West III account to a separate account, where the funds were held until the cards were closed. The transaction was identified for potential financial criminal activity. [Emphasis added]

According to the Senate report, Hunter Biden held one of the credit cards while James Biden and Sara Biden, Biden’s brother and sister-in-law, held three cards.

The Senate report states that Hudson West III LLC was first incorporated on April 19, 2016, more than a year before the China-linked line of credit was opened to fund purchases made by Hunter Biden, James Biden, and Sara Biden.

Hudson West III LLC had a number of business dealings with companies and Chinese nationals linked to the Chinese communist government, the Senate report states:

On Aug. 8, 2017, CEFC Infrastructure Investment wired $5 million to the bank account for Hudson West III. These funds may have originated from a loan issued from the account of a company called Northern International Capital Holdings, a Hong Kong-based investment company identified at one time as a “substantial shareholder” in CEFC International Limited along with Ye. It is unclear whether Hunter Biden was half-owner of Hudson West III at that time. However, starting on Aug. 8, the same day the $5 million was received, and continuing through Sept. 25, 2018, Hudson West III sent frequent payments to Owasco, Hunter Biden’s firm. These payments, which were described as consulting fees, reached $4,790,375.25 in just over a year. [Emphasis added]

The Senate report also accuses Hunter Biden of paying Russian and Eastern European women who are linked to prostitution or a human trafficking ring. Another detail reveals that one of Russia’s most powerful oligarchs paid Hunter Biden’s private equity firm $3.5 million in 2014.

John Binder is a reporter for Breitbart News. Follow him on Twitter at @JxhnBinder.

A Biden Ally and J Street

Vice Chair’s Company Offers Access to Senior Chinese Officials

And what it says about the

Democrat Party.

Wed Sep 16, 2020

Daniel Greenfield, a Shillman Journalism Fellow at the Freedom Center, is an investigative journalist and writer focusing on the radical Left and Islamic terrorism.

“Meet and build relationships

with China’s senior governmental and private sector leaders in your chosen area

of business,” the invitation on the site of Empire Global Ventures read. “Join

us for elite curated experiences with the people who decide the future of

China’s tech sector, craft and enforce its regulations, dominate its industries

and chart its path forward.”

The only thing more intriguing

than the invitation may be Empire Global Ventures whose CEO is also the Vice

Chair of the board of J Street and a prominent Democrat donor and fundraiser.

When Governor Andrew Cuomo

split up with his celebrity girlfriend after over a decade of shacking up

together, media accounts made sure to mention the role of Alexandra Stanto in

introducing the formerly happy couple.

As the CEO of Empire Global

Ventures, Stanton has come a long way since then. But the name of her company

closely echoes Empire State Development, an arm of the New York State

government, where Stanton had served as chief of staff from 2006 through 2008.

Stanton had worked for David

Patterson, back when he was in the State Senate. Then Eliot Spitzer, New York's

megalomaniacal Attorney General picked Patterson, the black and partly blind

Senate Majority Leader, as his running mate, to score with voters.

Patterson was never expected to

actually take the governor's office, but then Spitzer imploded, after

allegations of prostitution and thuggish behavior, and was forced to step down.

Stanton, who had been

Patterson’s deputy campaign manager for policy, and Sam Natapoff, her husband,

had scored six figure gigs with Empire State Development, with Sam earning the

grand title of, “Senior Advisor to the Governor of New York State for

International Commerce.” Today, Sam is the president of Empire Global Ventures

and writes editorials attacking President Trump over his work to help Americans

resist China’s abusive trade policies.

Stanton and her husband had

been pumping sizable amounts of money

into Paterson and Cuomo's war chests. Stanton alone had donated $10,000 to both

Paterson and Cuomo. But Stanton’s fundraising soon went national with an Obama

fundraiser running as much as $20,000 a ticket. And Obama named Stanton a

general trustee of the Kennedy Center.

The money has kept on rolling

out with Stanton donating thousands to Mayor Bill de Blasio and scoring an $8,000 per month consulting job

for City Hall.

By then, Stanton had become the

vice chair of J Street: a key anti-Israel lobby group.

Alexandra Stanton has spent the

last 12 years serving as Vice Chair of the anti-Israel group originally funded

by George Soros and has, in media accounts, been dubbed a “Jewish leader.”

Alexandra is the granddaughter

of Hellenic Lines shipping tycoon Pericles Callimanopulos. The Greek tycoon’s

funeral service was held at the Greek Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in

Manhattan.

Pericles' daughter and

Alexandra's mother, Domna Stanton, a feminist academic who is a longtime board

member of Human Rights Watch and had a prominent role at Planned Parenthood,

was named by De Blasio as one of New York City’s human rights commissioners.

Domna and her husband Frank, a

successful entrepreneur who had made his mark helping his brother Arthur import

the Volkswagen Beetle to America and trying to launch an early VCR, showed up

in Tom Wolfe's famously mocking profile of Leonard Bernstein's Black Panther

party.

The Stanton family has

connections by marriage to socialites from New York to D.C. and Domna’s Hamptons

garden parties are required attendance for celebrities and the smart set.

Alexandra Stanton has kept up

the tradition with cocktail parties attended by none

other than House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. She

was on the host committee for Hillary Clinton’s million dollar fundraiser for

Bill de Blasio, and, more recently, she took part in a Joe Biden fundraiser.

When Pelosi spoke at the

anti-Israel J Street’s gala, she thanked Stanton by name.

And when Obama descended into

ugly antisemitic attacks against Jewish opponents of the Iran Deal, Alexandra

Stanton was there to claim that he “has a right to combat what he thinks are

campaigns against him laden with non-facts and offensive statements.”

But Alexandra has a lot of

irons in the fire besides campaigning against the Jewish State.

These days, Stanton has also

been marketing Little Lives PPE face shields for children, scoring a FOX

profile, who described the politically connected Democrat, as a "mom".

The Wall Street

Journal mentioned Stanton's face shields for children in its

article on reopening schools alongside a quote from Randi Weingarten, the head

of the American Federation of Teachers.

The American Federation of

Teachers, the country's largest network of Democrat teachers' unions, had its

PPE purchases facilitated by Stanton and Empire Global Ventures.

Randi Weingarten, the AFT's

head, who recently faced criticism for claiming

that it's not safe for teachers to go back to school even while attending Al

Sharpton's 50,000 strong rally in D.C., was described as knowing "people

at Empire Global Ventures, a business development firm with experience in

China, where much of the world’s PPE is manufactured."

This wasn't the only strange

intersection between Empire, Democrats, and the coronavirus.

The sister-in-law of Chris

Cuomo, a CNN anchor and Governor Cuomo's brother, works for Empire Global

Ventures, and has been touting hypochlorous acid from Y2X Life Sciences as an

answer to the coronavirus. Cuomo's sister-in-law claimed that spraying

hypochlorous acid could keep businesses safe from the virus. Alexandra Stanton

and her husband are listed as Y2X Life Sciences advisers, along with Matt

Kennedy, RFK’s grandson and Joe Kennedy III’s brother, who sits on the boards

of Kennedy institutions, and had held down various positions in the Obama

administration, along with Dick Gephardt, the former Democrat House Majority

Leader.

In July, a job posting for

Empire Global Ventures described it as a medical products company.

What does Empire Global

Ventures actually do and whom does it know in China?

An invitation on the company's

site offers the opportunity to meet with "China’s senior governmental and

private sector leaders" and "China’s key decision makers".

Who are these senior government

officials and how does Empire have access to them?

These are all questions that

the media might be asking considering Alexandra Stanton’s long history of

access to top Democrat officials, including Obama and Biden, the large checks,

and Stanton’s key role at J Street, a domestic group whose funding came from

George Soros and, allegedly, Bill Benter, a

gambler operating out of Hong

Kong. They choose not to ask them.

Alexandra Stanton’s career

shows why people join the Democrats, not because they want a fairer world, but

because family and political connections pave the path to success, not for the

poor, but for wealthy families that are already exceedingly well connected in

that world.

The granddaughter of a Greek

shipping tycoon became a Democrat operative and fundraiser (and Jewish leader),

and while her company claims close access to the officials of a foreign

government, she has a powerful position in a foreign policy lobby giving her

access to Biden.

Considering Biden’s own

longstanding and problematic connections to China, and the role that the

Communist dictatorship is allegedly playing in boosting his campaign, this is

troubling.

It’s a good thing that the

media isn’t interested in asking any tough questions.