THE MEXICAN DRUG CARTELS HAVE OWNED THE LAST THREE MEX PRESIDENTS. BUT NO ONE WORKS HARDER FOR THEM THAN JOE BIDEN!

Mexican President Sends ‘Good Wishes’ to Jailed

Drug Lord, Discusses Release - WHY???

ILDEFONSO ORTIZ and BRANDON DARBY

Mexico’s president sent friendly greetings to an imprisoned drug lord who has been singled out by the U.S. as the mastermind behind the 1985 murder of DEA Agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena. The politician also said he is not opposed to releasing him from jail.

The powerful statements came during a morning news conference by Mexico’s President Andres Manuel Lopes Obrador where he spoke on the case of jailed Guadalajara Cartel Kingpin Miguel Angel Felix Gallardo also known as El Jefe de Jefes or the Boss of Bosses. The jailed drug lord once led the Guadalajara Cartel and recently granted a jailhouse interview to Telemundo. During that interview, a wheelchair-bound Felix Gallardo sent his support and blessings to Lopez Obrador.

“I thank him very much for his good wishes and I want him to understand my situation,” Lopez Obrador said. “I don’t want anyone to suffer, I don’t want anyone to be in jail.”

Lopez Obrador said that if Mexico’s Attorney General’s Office determined that he had no pending cases, he would be in favor of releasing Felix Gallardo due to his age and him having already spent time in prison. During the statement, Lopez Obrador did not make any mention of having the drug lord extradited to the U.S. to face prosecution for Camarena’s murder.

During the interview with Telemundo, the once-powerful drug lord denied having been a kingpin and claimed that he had spent 32 years in prison for crimes he did not commit. Felix Gallardo also claimed that he did not know why he is related to the case of Camarena, claiming that he never met the agent or had any connection to the leadership of the Guadalajara Cartel.

Felix Gallardo along with Rafael Caro Quintero are two of the living leaders of the Guadalajara Cartel and are believed to be the masterminds behind the kidnapping, torture, and murder of Camarena. As Breitbart Texas reported, a Mexican federal judge released Caro Quintero in 2013 in a sudden move before the U.S. government could extradite him. Since then the drug lord claimed that he wanted to retire but has since become one of the leaders of the Sinaloa Cartel.

Ildefonso Ortiz is an award-winning journalist with Breitbart Texas. He co-founded Breitbart Texas’ Cartel Chronicles project with Brandon Darby and senior Breitbart management. You can follow him on Twitter and on Facebook. He can be contacted at Iortiz@breitbart.com.

Brandon Darby is the managing director and editor-in-chief of Breitbart Texas. He co-founded Breitbart Texas’ Cartel Chronicles project with Ildefonso Ortiz and senior Breitbart management. Follow him on Twitter and Facebook. He can be contacted at bdarby@breitbart.com.

Sure-fire winner Obrador calls mass immigration to the United States a “human right” and says migrants “must leave their towns and find a life in the United States.” This razaista wants his lebensraum and he wants it right now.

If Obrador wins, President Trump might get him up to speed on America’s experience with regimes like that. And he might broach the subject of the $26.1 billion in remittances, an amount impossible without the bilking of American taxpayers on a massive scale.

“The Biden Immigration Agenda sacrifices the interests of the American People in order to serve the interests of foreign citizens, criminal cartels, and ultra-wealthy multinational corporations,” says the April 12 memo from Rep. Jim Banks (R-IN).

ProPublica misses the point of its own scoop on Mexican drug cartels funneling millions to AMLO's aides

ProPublica, the left-leaning investigative outfit, got itself a big scoop: That Mexico's president, Andres Manuel Lopez-Obrador, on the other side of Joe Biden's open border, has had close government aides apparently on the take from Mexican drug cartels in his climb to power.

In a long, long, engrossing story by longtime investigative reporter Tim Golden:

According to more than a dozen interviews with U.S. and Mexican officials and government documents reviewed by ProPublica, the money was provided to campaign aides in 2006 in return for a promise that a López Obrador administration would facilitate the traffickers’ criminal operations.

The investigation did not establish whether López Obrador sanctioned or even knew of the traffickers’ reported donations. But officials said the inquiry — which was built on the extensive cooperation of a former campaign operative and a key drug informant — did produce evidence that one of López Obrador’s closest aides had agreed to the proposed arrangement.

While the story is interesting, the obvious thing, lo obvio, sin embargo, is that the news outlet doesn't underline the significance of its own story.

Here is what in the news trade is known as the "nut graf," the sentence near the top that tells the readers why they need to keep reading:

The case raised difficult questions about how far the United States should go to confront the official corruption that has been essential to the emergence of Mexican drug traffickers as a global criminal force. While some officials argue that it is not the United States’ job to root out endemic corruption in Mexico, others say that efforts to fight organized crime and build the rule of law will be futile unless officials who protect the traffickers are held to account.

Democracy? Doing nothing? I would argue that that's not what this is about. That horse left the barn years ago.

What matters is that there's a border surge going on. Cities in the U.S. are being bankrupted, kids are being thrown out of their parks and schools, crime is skyrocketing, and fentanyl is pouring across the border, killing 109,000 Americans in the last year. It's the number one issue in the U.S. for voters and now we learn we're dealing with a Mexican president who's part of the problem.

The report found that government operatives very close to the sitting Mexican president found pretty conclusive evidence that AMLO's operatives were on the take from drug cartel leaders associated with the Sinaloa cartel, including the Beltran-Leyva group, and the now-Supermaxxed drug lord, Edgar Valdez Villareal, otherwise known as "La Barbie," who was busted in 2010 and extradited to the U.S. A former bagman of La Barbie's had come forward around 2008 after La Barbie, a notoriously ruthless killer, took out his brother and told the DEA what he knew about the AMLO camp's corruption dating from 2006. The DEA actually busted La Barbie based on the prospect of getting him to cooperate for a new operation to take out corrupt Mexican officials such as those associated with AMLO.

While this story is worth attention all by itself, it's the crisis now that draws attention. Were the cartels not so fat and happy on AMLO's watch, it's doubtful ten million illegals would have crossed so easily into the U.S.

.So while much of the story focuses on activity more than a decade ago, the eventual election of AMLO to Mexico's presidency in 2018 did have consequences, starting with an end to drug cooperation between the two countries which is to say, against the people-smuggling cartels.

First he sidelined the Mexican commando teams that had been the most trusted partner of U.S. law-enforcement and intelligence agencies. He then shut down a federal police unit that the DEA had trained and vetted to work with the Americans on big drug cases.

When DEA agents arrested a former Mexican defense minister, Gen. Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda, on drug-corruption charges in October 2020, López Obrador turned on the agency even more forcefully. With the military high command pressing the president to act in Cienfuegos’ defense, Mexican officials made clear that counter-drug cooperation was at risk. After U.S. Attorney General William Barr dropped the case and repatriated the general, López Obrador declared the Mérida accord “dead” and pushed through strict new limits on how U.S. agents could operate inside Mexico.

López Obrador’s long-standing promises to carry out a crusade against political corruption have produced almost no meaningful results.

So what's that again about why this should matter to us? A contest between doing nothing and Mexican democracy? Not exactly. Right now there's a border surge unlike any ever seen on this planet going on. That's why we pay attention to cartels and Mexican governments.

As Golden notes, the cartels have grown big and powerful on AMLO's watch as president, controlling about a quarter of the country. His cartel-fighting policy is "hugs, not bullets."

And more to the point, the millions of illegals entering the U.S. from our Southern border involveds the cartels, combined with the optimal-for-them situation of Joe Biden's open borders.

The cartels control who crosses the border, and illegal border crossers pay cartels "taxes" and "crossing fees" to get across.

Was AMLO involved here? Was Joe Biden involved here? Did money change hands at their levels, too?

With ten million illegals now in the U.S., that's a lot of money going to cartels with a Mexican government on the take and a Biden administration inviting them in.

It's known that corrupt Colombian officials and the entire Nicaraguan government have been enriching themselves from the border surge. Scattershot information indicates that Mexican officials benefit, too.

But this ProPublica report indicates that the corruption goes all the way to the top, with the Mexican government fully protecting its cartel buddies so they can exploit the migrants and themselves get rich. It certainly does explain AMLO's refusal to condemn Nicaragua or Venezuela, both likely narcostates, the way other countries in the hemisphere have, over various bad behaviors.

If AMLO is cartel'ed up, that changes the equation on the border surge going on right now.

If the Mexican government is a narcostate no different from Venezuela, then a hard hand, not negotiations, and not that secret agreement that Joe Biden and AMLO supposedly pulled off to damp down the surge until after elections, as reported by Todd Bensmann, is the only way to handle the surge.

Close the border. Sanction Mexican officials. Drop the free trade agreement. Threaten to reveal all that is known about public corruption, unless AMLO plays ball on the border surge. That we don't is a mystery. We don't have to overthrow their government, we just need to send them the kind of message they'll understand, being drug dealers and all. The law of the drug world is the law of the jungle. Strength, not concessions, is what is going to get their attention.

And while we are at it, Joe Biden would have known these things, being at the top of the U.S. intelligence pyramid. So is he, too, implicated? If drug dealers can buy off Mexican top officials, is it farfetched to wonder if maybe they bought off a few Americans on the other side? Funny how there is so little reporting, and so few arrests on this front, yet we have the perfect storm of cartel payoffs in Mexico and an open border in the states.

Wonder why.

Image: Screen shot from Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador video, via YouTube

Mexican President Calls U.S. Government Immoral After Media Reports Point to Cartel Funding His Campaign

Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador lashed out at the U.S. government, calling its agencies immoral for allowing three news outlets to publish a series of exposés detailing how the Sinaloa Cartel funneled millions into his 2006 failed presidential campaign.

In separate but connected news articles, Pro-Publica, Insight Crime, and the German news outlet GW.com published separate stories by Tim Golden and Anabel Hernandez, where each reported on a DEA investigation into how the Sinaloa Cartel had funneled millions into Lopez Obrador’s failed presidential bid. The criminal organization funneled cash to all of the candidates to hedge their bets and have friends in power regardless of the outcome.

In their report, both Golden and Hernandez explain in detail how, through their top lieutenants with the Beltran Leyva organization, including Edgar “La Barbie” Villarreal, the Sinaloa Cartel sent between $2-5 million in cash to Lopez Obrador’s campaign. The information in the publication matches witness testimony from the 2019 trial of Sinaloa Cartel boss Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, where top witnesses stated that money had been funded into presidential campaigns, including AMLO’s, Breitbart Texas reported.

In the story by Hernandez, she claimed that Lopez Obrador spoke on the phone directly with La Barbie to thank him for a donation and asked for his help in reducing violence once elected.

Lopez Obrador ran for president a total of three times, failing in the first two bids until he was successful in 2018 for a six-year term. This summer, Mexico will hold its 2024 presidential elections, where the Morena party founded by Lopez Obrador is one of the favorites.

On Tuesday, a furious Lopez Obrador used his morning news conference to respond to the claims — calling the stories slanderous.

“I don’t denounce the journalists, I don’t denounce the outlets,” Lopez Obrador said. “I denounce the United States Government for allowing these immoral practices.”

In dismissing the stories, Lopez Obrador said they were timed and coordinated as attacks on himself by those opposed to his government at a time when political campaigns are in full swing in Mexico.

Lopez Obrador’s press secretary, Jesus Ramirez Cuevas, pointed to the coordination of the stories and the timing, adding that there was no proof that implicated the president.

Ildefonso Ortiz is an award-winning journalist with Breitbart Texas. He co-founded Breitbart Texas’ Cartel Chronicles project with Brandon Darby and senior Breitbart management. You can follow him on Twitter and on Facebook. He can be contacted at Iortiz@breitbart.com.

Brandon Darby is the managing director and editor-in-chief of Breitbart Texas. He co-founded Breitbart Texas’ Cartel Chronicles project with Ildefonso Ortiz and senior Breitbart management. Follow him on Twitter and Facebook. He can be contacted at bdarby@breitbart.com.

Did Drug Traffickers Funnel Millions of Dollars to Mexican President López Obrador’s First Campaign?

Witnesses told the DEA that the money was provided in return for a promise that a future López Obrador government would tolerate the cartel’s operations.

https://www.propublica.org/article/mexico-amlo-lopez-obrador-campaign-drug-cartels?

Years before Andrés Manuel López Obrador was elected as Mexico’s leader in 2018, U.S. drug-enforcement agents uncovered what they believed was substantial evidence that major cocaine traffickers had funneled some $2 million to his first presidential campaign.

According to more than a dozen interviews with U.S. and Mexican officials and government documents reviewed by ProPublica, the money was provided to campaign aides in 2006 in return for a promise that a López Obrador administration would facilitate the traffickers’ criminal operations.

The investigation did not establish whether López Obrador sanctioned or even knew of the traffickers’ reported donations. But officials said the inquiry — which was built on the extensive cooperation of a former campaign operative and a key drug informant — did produce evidence that one of López Obrador’s closest aides had agreed to the proposed arrangement.

The allegation that representatives of Mexico’s future president negotiated with notorious criminals has continued to reverberate among U.S. law-enforcement and foreign policy officials, who have long been skeptical of López Obrador’s commitment to take on drug traffickers.

The case raised difficult questions about how far the United States should go to confront the official corruption that has been essential to the emergence of Mexican drug traffickers as a global criminal force. While some officials argue that it is not the United States’ job to root out endemic corruption in Mexico, others say that efforts to fight organized crime and build the rule of law will be futile unless officials who protect the traffickers are held to account.

“The corruption is so much a part of the fabric of drug trafficking in Mexico that there’s no way you can pursue the drug traffickers without going after the politicians and the military and police officials who support them,” Raymond Donovan, who recently retired as the Drug Enforcement Administration’s operations chief, said in an interview.

In their investigation, DEA agents developed what they considered an extraordinary inside source after they arrested the former campaign operative on drug charges in 2010. To avoid federal prison, the operative gave a detailed account of the traffickers’ cash donations, which he said he helped deliver. He also surreptitiously recorded conversations with Nicolás Mollinedo Bastar, the close López Obrador aide who the operative said had participated in the scheme.

Along with the sworn statements of other witnesses, the taped conversations indicated that Mollinedo was aware of and involved in the donations by one of the country’s biggest drug mafias, current and former officials familiar with the case said.

But some officials felt the evidence was not strong enough to justify the risks of an extensive undercover operation inside Mexico. In late 2011, DEA agents proposed a sting in which they would offer $5 million in supposed drug money to operatives working on López Obrador’s second presidential campaign. Instead, Justice Department officials closed the investigation, in part over concerns that even a successful prosecution would be viewed by Mexicans as egregious American meddling in their politics.

“Nobody was trying to influence the election,” one official familiar with the investigation said. “But there was always a fear that López Obrador might back away on the drug fight — that if this guy becomes president, he could shut us down.”

Since taking office in December 2018, López Obrador has led a striking retreat in the drug fight. His approach, which he summarized in the campaign slogan “Hugs, not bullets,” has concentrated on social programs to attack the sources of criminality, rather than confrontation with the criminals.

Yet with police and military forces generally avoiding confrontation with the biggest drug gangs, those mafias have extended their influence across Mexico. By some estimates, criminal gangs dominate more than a quarter of the national territory — operating openly, imposing their will on local governments and often forcing the state and federal authorities to keep their distance. The violence has hovered near historic levels, while the gangs’ extortion rackets and other criminal enterprises have metastasized into every layer of the economy.

The Mexican president’s chief spokesperson, Jesús Ramírez Cuevas, did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

The drug trade’s toll on Americans has never been more devastating. Fentanyl — most of which is produced in or smuggled through Mexico — is fueling the most lethal illegal-drug problem in American history. The estimated 109,000 overdose deaths recorded in 2022, most of them fentanyl-related, surpassed the fatalities from gun violence and automobile accidents combined.

The administration of President Joe Biden has been steadfast in its refusal to criticize López Obrador’s security policies, avoiding confrontation even when the Mexican president has publicly attacked U.S. law-enforcement agencies as mendacious and corrupt. The fentanyl explosion, while a growing political concern in Washington, remains less critical to Biden’s reelection prospects than blocking immigrants at the southern border — a challenge in which López Obrador’s cooperation is essential.

After asserting repeatedly that Mexico had nothing to do with fentanyl, López Obrador has recently taken a few modest steps to renew anti-drug cooperation. His government, though, continues to ignore U.S. requests for the capture and extradition of major traffickers, while Washington officials portray the relationship in rosy terms. At the end of a meeting with López Obrador in November, Biden turned to him and said, “I couldn’t have a better partner than you.”

A Justice Department spokesperson declined to comment on details of the DEA investigation into López Obrador’s political campaigns, citing a long-standing policy. But she added that the department “fully respects Mexico’s sovereignty, and we are committed to working shoulder to shoulder with our Mexican partners to combat the drug cartels responsible for so much death and destruction in both our countries.”

For decades, U.S. law-enforcement officials have shied away from investigating Mexican officials suspected of protecting the drug mafias, saying that pursuing such cases is fraught in a country that is uniquely sensitive to American interference. U.S. agencies have been even more hesitant to dig into the gangs’ involvement in electoral politics, even as they have become a primary source of funding for Mexican campaigns and have murdered scores of municipal, state and national candidates.

In the case of López Obrador, the DEA was slow to act on information about his 2006 campaign’s possible collusion with traffickers, several officials said. When the agency finally began to investigate in 2010, it was largely at the initiative of a small group of Mexico-based agents working with federal prosecutors in New York.

The Americans’ initial source was Roberto López Nájera, a tightly wound 28-year-old lawyer who turned up at the United States Embassy in 2008 and asked to speak to someone from the DEA. The two agents who came down from their fourth-floor offices heard a compelling story: For the previous few years, López Nájera told them, he had been a sort of in-house counsel to one of Mexico’s more notorious traffickers, Edgar Valdéz Villarreal.

The Texas-born gangster had been nicknamed “Ken” and then “Barbie” when he was a square-jawed high school linebacker with dirty-blond hair. By the mid-2000s, he had become one of the Mexican underworld’s more brutal enforcers. He was also a major trafficker, working with a larger mafia run by the Beltrán Leyva brothers, who in turn were part of the alliance known as the Sinaloa Cartel. On the Mexican side of the border, he was known as “La Barbie.”

According to López Nájera, La Barbie insisted that he start at the bottom, washing the traffickers’ cars and doing other menial chores before he was entrusted with more important tasks. He eventually managed some political contacts, paying bribes to police commanders and politicians, and oversaw cocaine shipments through the Cancún airport. After several years, however, López Nájera began to have differences with his boss, who thought him something of a slacker, officials said. In 2007, he returned from a long vacation in Cuba to find that his brother had disappeared, an apparent victim of La Barbie’s wrath. Going underground, López Nájera began plotting his revenge.

López Nájera quickly established his bona fides with the Americans, telling them the Beltrán Leyva gang had planted a mole inside the embassy. The man turned out to be an employee of the U.S. Marshals Service who had wide access to intelligence about the Mexican criminals being sought by the United States. Lured to the Washington, D.C., area on the pretense of a training junket, he was arrested and charged with federal drug crimes before agreeing to cooperate, officials said.

The DEA moved López Nájera to the United States and debriefed him extensively. In keeping with the new law-enforcement partnership known as the Mérida accord, U.S. officials then invited their Mexican counterparts to interview their prized source.

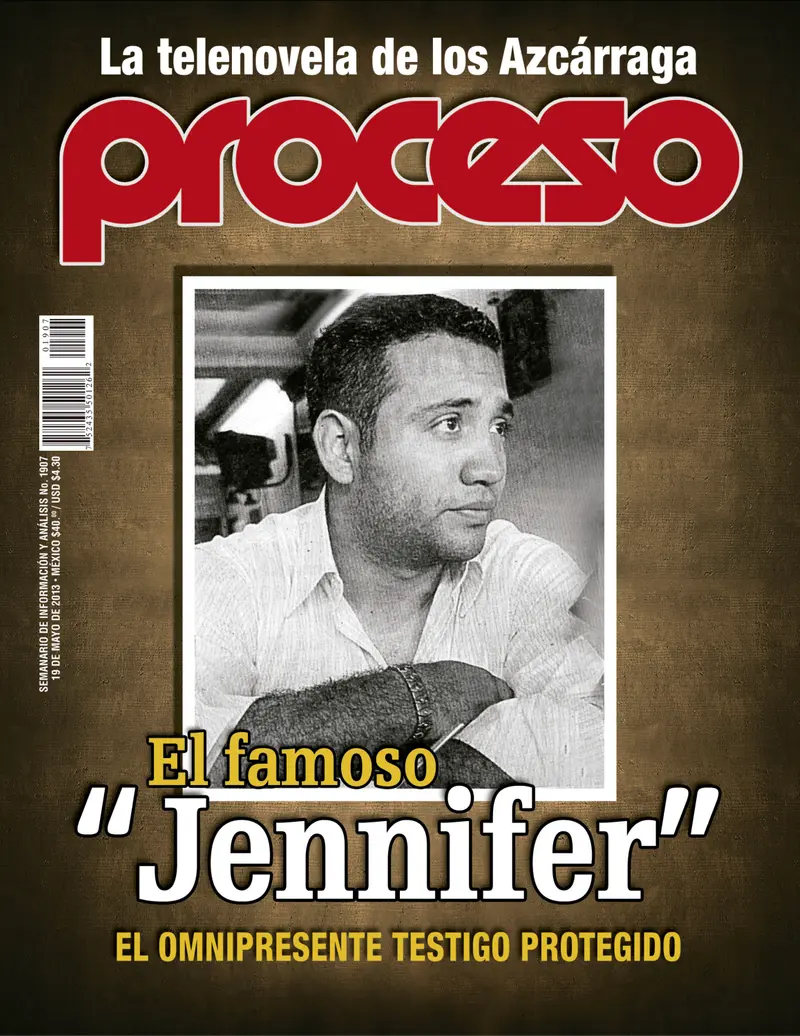

The Mexican court filings that resulted would identify López Nájera only by the code name “Jennifer.” His revelations would become the primary engine of “Operation Clean-up,” a headline-grabbing effort by the government of President Felipe Calderón to purge corrupt officials from federal law-enforcement agencies and the military.

The DEA was somewhat slower to take full advantage of its informer. It was only in the spring of 2010, more than two years after López Nájera had begun cooperating with the agency, that it began to focus on one of his more striking disclosures. In an interview in San Diego that DEA agents set up for a senior Mexican prosecutor, López Nájera described how La Barbie had summoned him to a January 2006 meeting at a hotel in the Pacific Coast resort of Nuevo Vallarta.

The man who had arranged the gathering was Francisco León García, the 38-year-old son of a mining entrepreneur from the northern state of Durango. Known as “Pancho” León, he was launching his candidacy for the Mexican Senate as a representative of López Obrador’s leftist alliance. He was friendly with one of La Barbie’s lieutenants, Sergio Villarreal Barragán, a towering former state police officer known as “El Grande,” and the two men thought they might be able to help each other, the agents were told.

Another businessman joined León at the meeting. The two said they were there with López Obrador’s knowledge and support, López Nájera recounted. In return for an injection of cash, León said, the campaign promised that a future López Obrador government would select law-enforcement officials helpful to the traffickers.

According to accounts of the negotiation that U.S. investigators eventually pieced together from several informants, the traffickers were told they could help to choose police commanders in some key cities along the border. More importantly, U.S. officials said, the traffickers were also told that López Obrador would not name an attorney general whom they viewed as hostile to their interests — seemingly granting them a veto over the appointment.

La Barbie agreed to the bargain and assigned López Nájera to meet with campaign officials in Mexico City and arrange the payoffs. (López Nájera did not respond to numerous attempts to contact him.) Soon after, officials said, he was introduced to Mauricio Soto Caballero, a businessman and political operative who was heading up an advance team under the campaign’s logistics chief, Nicolás Mollinedo.

In three deliveries over the next several months, the DEA was told, La Barbie’s organization gave Soto and others in the campaign about $2 million in cash. As the trafficker became more invested, López Nájera said, he provided support in other ways, too: Over the final weeks of the race, López Obrador traveled twice to the state of Durango for big, boisterous rallies organized by Pancho León, to which the gang donated heavily. One was so lavish — with a big-name band and thousands of partisans bused in from outlying towns and villages — that rival politicians demanded an investigation into León’s campaign funding.

The 2006 presidential race was a dead heat. When Mexico’s electoral tribunal declared Calderón the victor by half a percentage point, La Barbie was furious, López Nájera said. The drug boss came up with an impromptu plan to kidnap the president of the tribunal and force him to reverse the decision. A convoy of gunmen was dispatched to storm the court, turning back only when they discovered army troops guarding the area.

Having insisted he was the rightful winner, López Obrador rallied thousands of his supporters to Mexico City for a monthslong sit-in that covered a swath of the capital’s colonial center. According to López Nájera, La Barbie donated funds to help feed the protesters.

The DEA agents who heard López Nájera’s account understood that it would not be easy to build a criminal case, several officials said. Even if they could verify the allegations, high-level corruption cases were almost always hard to prove. Mexican officials used middlemen to insulate themselves from the traffickers who paid them. Politicians and criminals often protected one another; corroborating witnesses were usually reluctant to testify.

Most drug-related crimes also had a five-year statute of limitations. By the time the investigation got underway in earnest, some of the key events that López Nájera described had happened four years earlier.

The Mexican prosecutor who sat in on the López Nájera interview forwarded the allegations to more senior officials in Mexico City. But the Calderón government thought such a case would be too politically charged ahead of the 2012 election, former officials said.

DEA agents had better luck with the Southern District of New York, the powerful federal prosecutor’s office based in Manhattan. The head of the office’s international narcotics unit, Jocelyn Strauber, told them she thought the case was very much worth pursuing, current and former officials said. Strauber, who now leads the New York City Department of Investigations, declined to comment.

While the Southern District had rarely done Mexican drug-corruption cases, Calderón’s determination to work more closely with the United States gave the investigators some hope. U.S. agents had greater freedom to operate in Mexico than ever before; joint operations against traffickers had become commonplace. U.S. law-enforcement and intelligence agencies had helped the Mexican authorities arrest or kill leading figures of some big drug mafias, including the Beltrán Leyva organization. In May 2010, Mexico finally extradited Mario Villanueva, a former governor of Quintana Roo state, who eventually pleaded guilty in New York to funneling more than $19 million in traffickers’ bribes through U.S. accounts.

The investigators also recognized that López Nájera presented an unusual opportunity. Although he had been out of Mexico for more than two years, they thought he might be able to connect them to Soto, the former López Obrador campaign operative to whom he had delivered donations in 2006.

Soto was a gregarious, hustling business consultant with political ambitions of his own. He had worked in and out of government, finding angles and fixing problems with the bureaucracy. López Nájera said they had become friendly and that Soto had helped him with tasks unrelated to the campaign — acting as a front man for his purchase of an apartment in Mexico City’s tony Polanco neighborhood and helping him lease an office and renting a second apartment that La Barbie sometimes used on visits to the capital.

According to López Nájera, Soto had also introduced him to members of the 2006 campaign security team, connections that later proved useful when some of the men moved on to government security jobs. At one point, López Nájera recalled, Soto told him he might be interested in making money in the drug trade if the right opportunity arose.

With López Obrador preparing his second run for the presidency, Soto remained close to Mollinedo, who was still among the candidate’s most-trusted aides, officials said.

“Nico,” as Mollinedo was known, was something of a Mexican celebrity. Wherever López Obrador had gone during his five years as Mexico City’s mayor, Mollinedo had been beside him, at the wheel of the white Nissan sedan that López Obrador made a symbol of his contempt for the traditional excesses of Mexican politics. Mollinedo’s father had been a close friend and supporter of López Obrador’s since his days as a young activist in their native state of Tabasco.

Mollinedo had also been the subject of one of López Obrador’s first big political scandals, which erupted in 2004 with reports that the mayor’s driver earned the salary of a deputy secretary in the municipal cabinet. López Obrador brushed off “Nicogate,” as the newspapers called it, but made it clear that Mollinedo was much more than a chauffeur. He was the mayor’s personal aide and logistics coordinator and worked with his security team. Mollinedo acted as a sometime gatekeeper as well, filtering the people and proposals that clamored for the mayor’s attention.

By early 2010, a raft of Mexican officials had been arrested on López Nájera’s testimony, including a former top drug prosecutor and several senior police and military officials. His identity, though, remained a well-guarded secret, and he was confident that Soto believed he was still working for the narcos. They had last met in San Diego in late 2009, with DEA agents recording their conversation about whether Soto might want to get in on one of the drug deals López Nájera said he was putting together.

It made sense that López Nájera might be branching out on his own. La Barbie had stuck with the Beltrán Leyva brothers in what had been a two-year war with other factions of the Sinaloa Cartel. But now, as the Sinaloans gained the upper hand, La Barbie and the Beltrán Leyvas were fighting each other. The violence made headlines almost every day.

With the agents scripting his messages, López Nájera began texting Soto, officials familiar with the case said. In July 2010, they met at a hotel in Hollywood, Florida. Accompanied by an undercover DEA agent who posed as a Colombian cocaine supplier, López Nájera laid out his pitch: They had some deals in the works. They might need investors. The payoff would be big.

Soto said he was interested.

Weeks after the meeting in Florida, Soto flew to the Mexican-U.S. border to discuss a possible deal with the supposed Colombian trafficker and another undercover agent in McAllen, Texas. When he returned to McAllen in October, the two undercover agents told him they had 10 kilos of cocaine ready for him. But Soto balked, people familiar with the case said, insisting that he wasn’t ready to sell the drugs in the United States.

Needing some way to draw Soto back into their scheme, the undercover agents pressed him to safeguard the cocaine for several days until they could ship it to another buyer. As a reward, they would give him a kilo, worth about $20,000. The drugs were in a car parked nearby, one of the agents said, handing Soto a set of car keys. (There was no actual cocaine.) The conversation was recorded in its entirety.

Sometime after 2 o’clock the next morning, Soto returned to his room at a Courtyard Marriott. DEA agents were waiting.

On the wrong side of the border, without a lawyer or political connections, Soto did not take long to agree to cooperate. “He wasn’t the kind of guy who was ready to go to jail,” one official familiar with the case said. Later that day, after Soto waived his right to be prosecuted in Texas, he was flown to New York City on a commercial jet, sandwiched between a couple of agents in the back row.

Soto would thereafter become a confidential DEA source, known in the case file as CS-1. At the request of the DEA, ProPublica agreed not to identify him and other sources in the case. However, Soto was named in a Spanish-language article about the case published by DW News, the German state broadcast network.

After initially acknowledging messages from a ProPublica reporter, Soto did not respond to detailed questions about his role in the U.S. investigation.

Over several interviews with prosecutors from the Southern District, Soto confirmed that he had taken two deliveries of cash from López Nájera for the 2006 campaign and that a third delivery had been made by another envoy of La Barbie. Soto said the three contributions amounted to somewhat less than the $2 million that López Nájera had claimed, a discrepancy the agents attributed to customary skimming. Soto said he turned the money over to Mollinedo, people familiar with the case said.

In New York, Soto conferred with a court-appointed lawyer before agreeing to the government’s terms: If he continued to work secretly and speak truthfully with the investigators, he would be allowed to return to Mexico. His criminal conviction would remain sealed, and he would eventually be sentenced to the time he had “served” in federal custody — the several days he spent in McAllen and New York. Soto was brought before a federal judge and pleaded guilty to a single count of conspiracy to distribute cocaine.

U.S. officials understood that the arrangement posed serious risks. If Soto informed his colleagues in Mexico that he was being asked to set them up — or even if he just stopped returning phone calls — the Americans’ only leverage would be to expose his guilty plea and perhaps put out an international warrant for his arrest. But Soto would be able to expose their investigation.

The agents’ plan was to confirm the evidence they had gathered about the traffickers’ donations in 2006 and then to reenact a version of that scheme with López Obrador's incipient 2012 campaign — this time with recording devices in place. They called the investigation “Operation Polanco.”

To deploy Soto abroad as a covert or “protected-name source,” in the agency’s lexicon, the DEA had to submit its investigative plan to a group of Justice and DEA officials known as a Sensitive Activity Review Committee. A SARC (pronounced “sark”) is a screening process akin to a legal bomb squad. The panels examine undercover operations that involve the delivery of drugs or money to traffickers or the targeting of corrupt foreign officials; the lawyers try to deactivate the plans that might blow up on the department.

Although targeting the López Obrador campaign was an especially high-risk proposition, the SARC provisionally approved the plan in late 2010, officials said. The agents and prosecutors would have to return to the committee at least every six months for further review, and the scrutiny would intensify as they moved ahead.

The agents wanted to go big. They proposed offering the campaign $5 million in cash in return for promises that a López Obrador government would leave the traffickers alone. If Mollinedo or others in the campaign agreed, the agents would offer a down payment, maybe $100,000. They would then deliver the money to obtain hard evidence of the campaign’s complicity.

Some U.S. officials thought it was an auspicious moment for such a case. In August 2010, Mexican marines had captured La Barbie. Two weeks later, they took down El Grande, his lieutenant, who had attended the 2006 meeting in Nuevo Vallarta. Both men had been indicted on federal charges in the United States and, if extradited, might be enticed to cooperate in return for a reduction of their sentences. In a brief conversation after his capture, El Grande told a DEA agent he was willing to share information about corrupt Mexican officials, but only after he was moved to the United States, documents reviewed by ProPublica show.

But even as new pieces of the investigation came together, the Obama administration was growing concerned about the fallout from another undercover operation, what became known as “Fast and Furious.” Without informing Mexican officials, agents of the Justice Department’s Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives allowed hundreds of high-powered weapons to be shipped illegally into Mexico so they could track them into the hands of drug gangs. The tracking failed, however, and the weapons were later tied to shootings that killed or wounded more than 150 Mexicans as well as the murder of a U.S. Border Patrol agent. The Calderón government was outraged, and the tensions seemed to threaten bilateral cooperation once again.

“Things just came under a different level of scrutiny after Fast and Furious,” a former Justice Department official said. “At that point, everybody was in self-preservation mode.”

Still, American officials had some reason to hope that Mexico’s leaders might countenance — and keep secret — their investigation. Their ultimate target, López Obrador, was Calderón’s hated political rival. The DEA chief in Mexico City would inform the president’s intelligence chief, who was considered particularly trustworthy, and ask him to discuss the case only with Calderón.

The next phase of the investigation began well. DEA agents learned that the businessman who had accompanied Pancho León to the 2006 Nuevo Vallarta meeting was traveling to Las Vegas. When confronted by agents at the Bellagio Hotel & Casino, the businessman confirmed much of what Soto and López Nájera had said. He even mentioned a striking detail that López Nájera had noted: At the 2006 meeting in Nuevo Vallarta, León had given La Barbie a gift. Having heard that the trafficker collected watches, he brought a $20,000 Patek Philippe as a token of his respect.

The prosecutors initially thought they did not have enough evidence to arrest the man, so the agents let him return home after he promised to testify as a witness in any future criminal trial. The investigators had no hope of getting to León: In February 2007, months after losing his Senate race, he disappeared — the rumored victim of a drug-mafia murder.

In Mexico City, DEA agents rehearsed Soto, fitted him with a recording device and, in April 2011, sent him to talk with Mollinedo. It was a disaster. “He was terrified,” a former official recalled. Whether Soto mishandled the equipment or deliberately turned it off wasn’t clear, but he returned with a truncated recording that was often unintelligible because of background noise.

A second attempt the following month yielded about an hour of tape. It was clear from that conversation that Mollinedo knew about the 2006 transaction, people familiar with the case said. He seemed worried about two former members of the campaign security team, who had recently been jailed and might be pressured to reveal what they knew about the traffickers’ contributions. The officials said Mollinedo also mentioned friends in the Mexican attorney general’s office who might help protect him and Soto.

Although it was clear the two men were talking about the 2006 donations, Soto did not press Mollinedo to be more explicit or to incriminate himself more directly. “He never said, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about’ or ‘I don’t know any of those people.’ There wasn’t anything said that cleared him,” one former official said of Mollinedo. “But the tape did not freshen up the conspiracy as much as was needed.”

In an interview, Mollinedo denied that he had ever received donations from drug traffickers and disputed the idea that López Obrador would ever tolerate such corruption. “We didn’t manage money,” he said, referring to his logistics team, adding that it only handled funds it was given to spend on transportation and other campaign expenses.

After going over the recordings, the New York prosecutors were underwhelmed, former officials said. For such a sensitive and risky case, they felt the evidence needed to be nearly irrefutable. The agents nonetheless proposed to move ahead with the sting operation directed at Mollinedo and other López Obrador aides. How they proceeded from there — and whether they went after López Obrador and other politicians in his orbit — would depend on what the agents learned.

When the SARC met to review the case again, just before Thanksgiving 2011, Justice and DEA officials in Washington, D.C., were joined by video link with senior DEA agents in Mexico City and New York. This time, however, the questions were sharper, several people familiar with the meeting said. Even if U.S. Embassy officials informed only trusted Mexican officials, the information could easily leak out, some officials said, and it could be explosive.

DEA representatives at the meeting emphasized that they were not seeking to affect the Mexican election, officials familiar with the meeting said. But they also made the point that if Mexico elected a president who came to office in debt to powerful drug traffickers, the consequences could be catastrophic for the two countries’ law-enforcement partnership.

Not long into the meeting, the video link to Mexico City went down — a common occurrence with the technology of the time. Without the main DEA group working on the case, the tone of the discussion shifted, two people present said. Justice Department lawyers talked about the huge risks of the operation, the uncertain evidence and the still-volatile aftermath of the Fast and Furious scandal, which had prompted some Republicans in Congress to call for the resignation of Attorney General Eric Holder.

The agents and prosecutors got word of the SARC decision days later — the operation was being shut down.

In May 2012, the Mexican government extradited El Grande. When agents were able to ask him on U.S. soil about the donations to the López Obrador campaign, he confirmed that La Barbie had made them after the meeting in Nuevo Vallarta, two officials said.

López Nájera’s star turn as Jennifer in Operation Clean-up was short-lived.

When the Calderón government was replaced in December 2012, it was not by López Obrador and his leftist alliance but by the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, the political party that had held the country in a corrupt, authoritarian grip for more than 60 years until 2000. The new president, Enrique Peña Nieto, quickly pulled back from his predecessor’s close law-enforcement cooperation with the United States. Part of that shift was an effort by Peña’s attorney general, Jesús Murillo Karam, to disparage and reverse the previous administration’s prosecutions of corrupt officials.

According to three officials familiar with the events, Mexican prosecutors continued to interview López Nájera in the United States, but now they sought to exploit gaps and contradictions in his testimony. They asked him to corroborate new details of events he had described, sometimes suggesting specific dates, only to have other witnesses produce alibis for the dates López Nájera had confirmed.

A flurry of Mexican news stories, many of them driven by apparent government leaks, assailed López Nájera as a well-paid liar for the previous regime. Proceso, the country’s leading investigative magazine, revealed his identity with a cover photograph that U.S. officials said came from the Mexican attorney general’s office. Virtually all the officials jailed in Operation Clean-up were released after the charges against them were dropped.

What did not become public was that U.S. law-enforcement officials took the opposite view. While they noted that López Nájera had been inconsistent or mistaken on some points in his statements, almost everything else he had told them held up. So even as López Nájera became a symbol in Mexico of the justice system’s failures, the DEA judged him credible and continued to work with him.

Even before López Obrador took office in December 2018, U.S. officials began to review information from the DEA investigation as part of their effort to assess the new president’s willingness to work with them against the mafias, people briefed on the effort said. But the new Mexican leader soon answered that question himself.

First he sidelined the Mexican commando teams that had been the most trusted partner of U.S. law-enforcement and intelligence agencies. He then shut down a federal police unit that the DEA had trained and vetted to work with the Americans on big drug cases.

When DEA agents arrested a former Mexican defense minister, Gen. Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda, on drug-corruption charges in October 2020, López Obrador turned on the agency even more forcefully. With the military high command pressing the president to act in Cienfuegos’ defense, Mexican officials made clear that counter-drug cooperation was at risk. After U.S. Attorney General William Barr dropped the case and repatriated the general, López Obrador declared the Mérida accord “dead” and pushed through strict new limits on how U.S. agents could operate inside Mexico.

López Obrador’s long-standing promises to carry out a crusade against political corruption have produced almost no meaningful results. Although a smattering of corruption charges were announced early in the administration — nearly all against the president’s political adversaries — almost none were successfully prosecuted.

However, López Obrador did call into question the previous administration’s discrediting of Operation Clean-up. In August 2022, his government arrested Murillo Karam on charges of helping cover up the 2014 disappearances of 43 students in the state of Guerrero. Months later, the government announced that the former attorney general would also face corruption charges in connection with more than $1.3 million in hidden income and illicit contracts from which he was said to have profited during his time in office. Murillo Karam has denied the charges.

The president’s former close aide, Mollinedo, left López Obrador’s side after the 2012 campaign to go into business. He later joined Soto in trying to establish a new political party focused on the environment. The effort fizzled out within a year.

Mollinedo told ProPublica that he remains deeply loyal to the president. Although he and his family have been accused of growing wealthy from their political connections, he said his business endeavors have been entirely aboveboard.

Update, Jan. 31, 2024: At his regular morning news conference following the publication of ProPublica’s article, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador denounced the story as “completely false.” He added, “There is not a shred of evidence.”

He suggested that ProPublica’s story was a product of “management of the media” by the U.S. State Department and other powerful government agencies. “The DEA must say if this is true, not true, what was the investigation, what proof does it have.”

“Joe Biden is great on immigration. I guess depends on your perspective. If you’re a human trafficker, or drug dealer, you’d give him an A-plus, but theAmerican people would give him an F. The crisis at our border was not only entirely predictable, it was predicted. I predicted that if you campaign all year long on open borders, amnesty, and health care for illegals, you’re going to get more migrants at the border. That’s what’s happened since the election.” SEN. TOM COTTON

JUDICIAL WATCH:

“The greatest criminal threat to the daily lives of American citizens are the Mexican drug cartels.”

http://mexicanoccupation.blogspot.com/2016/12/the-american-border-with-narcomex.html

“Mexican drug cartels are the “other” terrorist threat to America. Militant Islamists have the goal of destroying the United States. Mexican drug cartels are now accomplishing that mission – from within, every day, in virtually every community across this country.” JUDICIAL WATCH

CUT AND PASTE YOUTUBE LINKS

How Cartels Took Over California's Desert and Turned It to Lawless Land | Dawn Rowe

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CX21ldNfefA

For starters, let's define the "fentanyl crises" for what it really is: Chemical warfare, effectively perpetrated on the American people by the Chinese communist government and their Mexican-cartel allies. This administration's open border, which is clearly an intentional policy, marks Biden and Harris as co-conspirators in what's arguably the CCP's chemical-weapons assault on U.S. citizens. RICHARD MORSE

State Department to U.S. citizens: Stay out of Mexico

How's this for buried news among the side effects and unintended consequences of Joe Biden's open borders?

The State Department has issued a bone-chilling warning to U.S. citizens to stay the hell out of Mexico.

It was a "top-tier" admonishment to not set foot in six Mexican states that tourists love to go to, and to be very careful in all of the remaining ones.

According to local San Diego indy news station KUSI:

SAN DIEGO (KUSI) – The State Department issued the strongest possible ‘do no travel’ warning to six states in Mexico due to threats of crime and kidnapping in the country.

All other regions in Mexico are on watch by the U.S. government. As Spring Break approaches, the State Dept. warned that even in resort towns, cartels have established close ties with local businesses.

Immigration Attorney Esther Valdes Clayton went live with KUSI’s Lauren Phinney to discuss the crisis South of U.S. borders.

The story features an embedded video with Valdes Clayton, speaking in bone-chilling terms about what is happening to Americans as they head on out to tourist hotspots in Mexico for vacation, noting that Spring Break, which is a rite of passage for college students, is around the corner.

Valdes Clayton described the horrific story of what happened to a 33-year-old Orange County public defender celebrating his first wedding anniversary in Rosarito Beach, a lovely resort town on the Pacific best known for its fish tacos that's just a short driving distance south of the O.C., San Diego and Tijuana. The media reported the story of Elliot Blair here.

What she described, with firsthand information, was not what was reported in the press -- that he died in "an unfortunate accident" as Mexican officials claimed, falling off his hotel balcony or getting drunk and getting knocked out. That was what got reported in the news, at ago, along with a few disclaimers that Blair's family was suspicious that he was killed, but few details were laid out and little else came of the story until a few days ago.

Valdes Clayton said that the family investigated what it could and found that Blair's body numerous significant broken bones as if he had been beaten to death, along with rug burns as if he or his body had been dragged through the hotel before being dumped under his balcony window. Blair and his wife had resisted an extortion attempt earlier, which is a significant detail.

It's an outrageous attack on Americans and there are a lot of these incidents for the State Department to raise Cain with the Mexicans about, because apparently the Mexicans are in denial, or well, quite likely cartel'ed up and doing nothing. That explains why warnings like this go out and why they are quite likely perfectly plausible. They can't do a thing about these killings and kidnappings and they know the Mexican officials won't, either.

Which rather raises more questions about Joe Biden's open borders policies and why there's such a sudden upsurge in attacks and assaults on Americans.

Border surges, such as Joe Biden's, are a cash bonanza to Mexico's cartel members. They have made billions off these border surges as migrants pay the "crossing free" if not the human smuggling fee, which can run in the thousands and even tens of thousands of dollars per head. With 2,500 crossing each day into just the El Paso corridor (the San Diego one is said to be even busier) a lot of money is rolling in, and this explains why cartels have grown in size with recruiting, and why they are shutting down border cities in places such as Tijuana, as well as fighting with each other for control of the spoils. It's created a boomtime atmosphere in these areas controlled by the cartels, and activated the remaining criminal element to try to scarf up more for themselves, too. This is not to say that the cartels are not responsible or the killings and kidnappings, too -- most likely, they are. Big money is at stake, and crime is now paying. Valdes Clayton makes this point about money, too.

The cartels also know that Joe Biden won't protect Americans through their own border, so they're pretty certain that he's not going to do much to worry them if they shake down visiting Americans for every penny they have, if not kidnap them for ransom, or simply beat them to death as seems to have happened to Blair.

A border warning, such as the State Department has issued, is a last-resort measure, given the major trade and tourist ties the U.S. has with Mexico, a throwing up of the hands with a warning to Americans that Biden's influence is nil in Mexico and there is nothing they can do to help if they become targets of cartels.

That's a high price for Americans to pay for open-borders based on a president who won't do his sworn job. Here's the scary part: It's not going to get better, and no one should be surprised if it starts spilling over here in more visible cases against Americans completely unconnected to cartels and their activity. It's a chilling prospect, and this lawyer's warning is a bellwether of what's ahead.

Image: Screen shot from ABC Good Morning America video, via YouTube

El Chapo’s Wife Arrested in Virginia on Drug Conspiracy Charge

ILDEFONSO ORTIZ and BRANDON DARBY

22 Feb 202140

2:05

The wife of notorious Mexican kingpin Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman faces drug trafficking charges after U.S. agents arrested her in Virginia. She is expected to appear before a judge Tuesday, February 23.

The arrest took place Monday at Dulles International Airport where authorities arrested 31-year-old Emma Coronel Aispuro, a prepared statement from the U.S. Attorney’s Office revealed. Prosecutors claim Coronel took part in drug trafficking conspiracies and helped plan her husband’s second prison escape in 2015 from the Altiplano facility in Mexico. According to the U.S. Attorney’s Office, Coronel is charged with one count of drug trafficking conspiracy.

El Chapo is serving a life sentence in a U.S. prison after a widely publicized trial where Mexico’s highest levels of government were named as having worked with the Sinaloa Cartel. Witness testimony points to current Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador and his predecessor as having received money from El Chapo’s associates.

In October 2019, Lopez Obrador received significant criticism after he ordered authorities to release one of El Chapo’s sons in Sinaloa. Lopez Obrador claimed that the move was done to avoid bloodshed since the cartel gunmen threatened acts of extreme violence.

Ildefonso Ortiz is an award-winning journalist with Breitbart Texas. He co-founded Breitbart Texas’ Cartel Chronicles project with Brandon Darby and senior Breitbart management. You can follow him on Twitter and on Facebook. He can be contacted at Iortiz@breitbart.com.

Brandon Darby is the managing director and editor-in-chief of Breitbart Texas. He co-founded Breitbart Texas’ Cartel Chronicles project with Ildefonso Ortiz and senior Breitbart management. Follow him on Twitter and Facebook. He can be contacted at bdarby@breitbart.com.

GRAPHIC EXCLUSIVE: Mexican Authorities Probe Alliance Between Cartels to Hold Turf near Texas

Photo: Breitbart Texas/Cartel Chronicles

Photo: Breitbart Texas/Cartel Chronicles

ILDEFONSO ORTIZ, BRANDON DARBY and GERALD TONY ARANDA

22 Feb 2021178

2:48

Authorities are investigating the inner workings of a new alliance between two of the most violent cartels in Mexico. Information exclusively confirmed to Breitbart Texas by top security officials suggests Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generacion (CJNG) and La Linea are joining forces against the Sinaloa Cartel.

Breitbart Texas consulted top Mexican federal law enforcement sources who revealed meetings at the highest levels over concerns that an alliance was appearing to be forged. The allied goal is to stop the spread of factions from the Sinaloa Cartel as they make inroads in the border state of Chihuahua–putting La Linea’s interests near Texas at risk. Preliminary information does not yet specify if the alliance will lead to additional gunmen, weapons, or financial assistance from Jalisco. The turf war in Chihuahua has already led to more than 200 high-impact crimes since the beginning of 2021.

Chihuahua is home to Ciudad Juarez, a border city that once was known as the murder capital of the world after the long history of disputes between the Juarez Cartel (aka La Linea) and the Sinaloa Cartel. In a similar fashion, CJNG is currently considered the biggest rival to the Sinaloa Cartel as the two fight throughout Mexico for turf.

Last week, a fierce shootout between a faction of the Sinaloa Cartel known as Gente Nueva and La Linea led to a gory scene that sparked controversy after gunmen left three severed heads on an SUV. The Gente Nueva faction is currently led by Antonio Leonel “El 300” or “Bin Laden” Camacho Mendoza.

Mexican Presidents Deny They Took Bribes from El Chapo

https://www.breitbart.com/border/2018/11/14/mexican-presidents-deny-they-took-bribes-from-el-chapo/

Two former Mexican presidents publicly denied taking bribes from the Sinaloa Cartel. The statements came after the legal defense for Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera made contrary claims this week.

The drug lord is facing several money laundering and drug trafficking charges at a federal trial in New York. In his opening statement, defense attorney Jeffrey Lichtman spoke of bribes “including the very top, the current president of Mexico and the former.”

Soon after the statements became public, Mexico’s government issued a statement denying the allegations. Eduardo Sanchez, the spokesman for current Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto said the statements were false and “defamatory.”

El gobierno de @EPN persiguió, capturó y extraditó al criminal Joaquín Guzmán Loera. Las afirmaciones atribuidas a su abogado son completamente falsas y difamatorias

— Eduardo Sánchez H. (@ESanchezHdz) November 13, 2018

Former Mexican President Felipe Calderon took to social media to personally deny the allegations, claiming that neither El Chapo or the Sinaloa Cartel paid him bribes.

Son absolutamente falsas y temerarias las afirmaciones que se dice realizó el abogado de Joaquín “el Chapo” Guzmán. Ni él, ni el cártel de Sinaloa ni ningún otro realizó pagos a mi persona.

— Felipe Calderón (@FelipeCalderon) November 13, 2018

Under Guzman’s leadership, the Sinaloa Cartel became the largest drug trafficking organization in the world with influence in every major U.S. city.

The allegations against Pena Nieto are not new. In 2016, Breitbart News reported on an investigation by Mexican journalists which revealed how Juarez Cartel operators funneled money into the 2012 presidential campaign. The investigation was carried out by Mexican award-winning journalist Carmen Aristegui and her team. The subsequent scandal became known as “Monexgate” for the cash cards that were given out during Peña Nieto’s campaign. The allegations against Pena Nieto went largely unreported by U.S. news outlets.

Ildefonso Ortiz is an award-winning journalist with Breitbart Texas. He co-founded the Cartel Chronicles project with Brandon Darby and Stephen K. Bannon. You can follow him on Twitter and on Facebook. He can be contacted at Iortiz@breitbart.com.

Brandon Darby is the managing director and editor-in-chief of Breitbart Texas. He co-founded the Cartel Chronicles project with Ildefonso Ortiz and Stephen K. Bannon. Follow him on Twitter and Facebook. He can be contacted at bdarby@breitbart.com.

Should We Invade Mexico?

https://townhall.com/columnists/kurtschlichter/2018/07/05/should-we-invade-mexico-n2497140?utm_campaign=rightrailsticky2

One fact a lot of Americans forget is that our country is located right up against a socialist failed state that is promising to descend even further into chaos – not California, the other one. And the Mexicans, having reached the bottom of the hole they have dug for themselves, just chose to keep digging by electing a new leftist presidente who wants to surrender to the cartels and who thinks that Mexicans have some sort of hitherto unknown “human right” to sneak into the United States and demographically reconquer it. There’s a Spanish phrase that describes his ideology, and one of the words is toro.

Mexico is already a failed state, crippled by a poisoned, stratified culture and a corrupt government that have somehow managed to turn a nation so blessed with resources and hardworking people into such a basket case that millions of its citizens see their best option as putting themselves in the hands of gangsters to cross a burning desert to get cut-rate jobs in el Norte. It is a country dominated by bloody drug/human trafficking cartels that like to circulate videos of their members carving up living people. They hang mutilated corpses from overpasses and hijack busloads of citizens to rape and slaughter for fun. Whole police agencies are owned by the cartels. Political candidates live in fear of murder. The people are scared. And this chaos will inevitably grow and spread north.

The gangs are already here, importing the meth and fentanyl that are slaughtering tens of thousands of Americans a year after coming across the border the Democrats refuse to defend. Let’s not even think about the other foreigners, like Islamic terrorists, who might exploit this vulnerability. “Abolish ICE,” the liberals screech, yet what they really mean is “Erase that line on the map.” But that line is all that is keeping the bloodshed in Mexico at bay for now. You can stand on US soil, look south, and see places where the rates of killing dwarf those of the Middle Eastern killing fields you see on TV.

The chaos in Mexico will spill over the theoretical border. It is just a matter of time. Normal Americans know it. As my book upcoming book Militant Normals explains, the establishment willfully ignoring their legitimate concerns about border security is a big part of why Normals are getting militant. The Democrats, and the GOP donor class stooges, have a vested interest in ignoring the issue, and they will insure that both the political class and the hack media will continue to play ostrich. Already there are Americans, on American soil, living near the border who cannot venture outside at night on their own property for fear of being murdered because of foreigners invading out territory. This is intolerable for any sovereign country. Yet there is a huge liberal constituency, abetted by GOPe fellow travelers, not merely willing to tolerate the invasion but who actively want to increase the flow.

When the 125-million-man criminal conspiracy that is Mexico falls apart completely, as it will, we are going to have to deal with the consequences. Watch the flood of illegals become a tsunami, a real refugee crisis instead of today’s fake one. Watch the criminal gangs and pathologies of the Third World socialist culture they bring along turn our country into Mexico II: Gringo Boogaloo. And importing a huge mass of foreigners, loyal to a foreign country and potentially susceptible to the reconquista de Aztlan rhetoric of leftists, both among them and among our treacherous liberal elite, would create a cauldron for brewing up violent civil upheaval right here at home.

So, what do we do? We defend ourselves, obviously. But how?

Should we be reactive? Should we continue the fake defense of our border we’re pretending to conduct today? Or should we seriously defend ourselves by building a wall and truly guarding it, and by deporting all illegals we catch inside. But would that even be enough when Mexico collapses?

It’s time to ask: Should we be proactive?

Should we invade Mexico? Should we send our military across the Rio Grande to secure the unstable territory, annihilate the criminal infestation that suppurates there, and impose something resembling order? One thing is certain. The border charade we tolerate today can’t be an option – it’s an open door to the fallout from the failing state next door.

Militarily, there are three obvious courses of action (I had input on this by several people familiar with the issue; none of this reflects any actual operational planning that I or anyone I spoke to is aware of).

One is the Buffer Zone option. We move in and secure a zone perhaps 50-100 miles inside the country, aggressively targeting and annihilating criminal gangs – we know where these bastards are – and thereby seal off the threat until Mexico is secure again and then return the territory once we are assured America is safe.

This is doable, but it would take a huge chunk of our military forces (we would need to call up most of our reserves). The conventional Mexican forces that fought would last for about un momento before being vaporized, but it would spark at a minimum a low-intensity insurgency by cartel hardliners and, at worst, a large one by Mexican patriots, probably using guns left over from when the Obama cartel was shipping them south. Regardless, it would be expensive. There is the “You break it, you buy it” rule. We would end up administering a long strip of territory full of people living, largely, in what Americans consider abject poverty. They would become our problem. Moreover, there is the giving back part – millions of Mexicans might find they like being nieces and nephews of Tio Sam.

The second is Operation Mexican Freedom, a much more ambitious campaign that would recognize what liberals already think – that Mexico and America are one country. Our forces would conquer the nation by driving all the way south, perhaps with an amphibious landing at Veracruz for old times sake and because the Marines would insist, then seal the Mexican-Guatemalan border. We would annex the whole country, making it a colony like Puerto Rico (A dozen new senators from Old Mexico? Nogracias). We would kill every terrorist drug gang member and take or torch everything they own, while simultaneously deporting every illegal from the US-Canada border to the Mexican-Guatemalan border.

Of course, that would take up pretty much our entire military and certainly spark some sort of endless guerilla conflict. We would be stuck in another bloody, expensive fight to make a Third World country cease sucking despite itself. It would make the Iraq War seem cheap. But, on the plus side, Bill Kristol and his bombs away pals would probably be excited.

Oh, in both cases the Europeans would be outraged, which is a powerful argument for these options.

Still, no. Invading Mexico is a bad idea. It would convert the problems of Mexico, created and perpetuated by Mexicans, into our problems. We tried that in the Middle East. It doesn’t work. Making Mexico better for Mexicans is not worth the life of one First Infantry Division grenadier.

But the consequences in America are our problem, and we must solve it. That brings us to the third option – Forward Defense. Think Syria in Sinaloa. We secure the border, with a wall of concrete and a wall of troops, perhaps imposing a no-fly/no-sail zone (excepting our surveillance and attack aircraft), and then conduct operations inside Mexico using special operations forces combined with airpower to target and eliminate the cartels. We would also identify friendly local Mexican police and military officials and support their counter-cartel operations outside of our relationship with the central government – they would be the face of the fight. We would channel Hernán Cortés and, in essence, we would allow friendly Mexican allies, with our substantial direct and indirect support, to create our buffer zone for us.

This avoids the problem of buying Mexico’s problems and making them ours. It’s somewhat deniable; everyone could save face by denying the Yankees have intervened. But the cartels would not just sit there and take it. They would target Americans and probably do so inside the United States. Yet that’s going to happen anyway eventually. This course of action risks the lowest number of US casualties, but perhaps the highest number of Mexican losses.

So no, we should not invade Mexico. There are no good military options, and none are necessary or wise today, but we may eventually have to choose between bad options. Mexico is failing more and more every day. We are not yet at the point of a military solution, but anyone who says that day can never come is lying to himself and to you. We need a wall, but more than that, we need the commitment to American security and sovereignty that a wall would physically represent. The issue is very clear, and we need to be very, very clear about it when we are campaigning in November. Border security. Period.

Are we going to prioritize the interests of liberals who want to replace our militant Normal voters with pliable foreigners and establishment stooges who want to please rich donors by importing countless cheap foreign laborers, or are we going to prioritize the economic security and the physical safety of American citizens by securing our border no matter what it takes?

Come on, open borders mafia, let’s have that discussion. Bueno suerte with that at the ballot box.

THE NARCOMEX INVASION OF AMERICA…. By invitation of the Democrat Party

https://mexicanoccupation.blogspot.com/2018/11/trump-seeks-deal-with-narcomex-as.html

There are many reasons why, for the first time, the government of Mexico would agree to work cooperatively with the United States over an extremely serious immigration-related issue. It is likely, of course that President Trump was not just posturing when he said he would cut off aid to Mexico and other countries who permit the United States to be invaded by illegal aliens.

Under Guzman’s leadership, the Sinaloa Cartel became the largest drug trafficking organization in the world with influence in every major U.S. city.

The allegations against Pena Nieto are not new. In 2016, Breitbart News reported on an investigation by Mexican journalists which revealed how Juarez Cartel operators funneled money into the 2012 presidential campaign. The investigation was carried out by Mexican award-winning journalist Carmen Aristegui and her team….The subsequent scandal became known as “Monexgate” for the cash cards that were given out during Peña Nieto’s campaign. The allegations against Pena Nieto went largely unreported by U.S. news outlets.

Former Mexican military chief pleads not guilty to US drug trafficking charges

Retired Gen. Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda, the Mexican defense secretary from 2012 to 2018, appeared in a US federal court in Brooklyn last Thursday, following his Oct. 15 arrest at Los Angeles International Airport.

Cienfuegos, referred to as “The Godfather” in the indictment, pleaded “not guilty” to charges of conspiracy, drug trafficking to the United States and money laundering. Between December 2015 and February 2017, according to the court filing, “in exchange for bribe payments, he permitted the H-2 Cartel—a cartel that routinely engaged in wholesale violence, including torture and murder—to operate with impunity in Mexico.”

The prosecutors claim to have thousands of incriminating BlackBerry Messenger exchanges with the H-2 Cartel, a remnant of the Beltrán Leyva Cartel, they obtained through US phone-tapping operations against Cienfuegos and cartel members. One message allegedly indicates that he provided assistance for far longer to another organization, which is widely believed to be the Sinaloa Cartel.

![]()

General Cienfuegos in 2018 receiving award at Pentagon's Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies (Credit: NDU Audio Visual)

The trial of Cienfuegos is the latest in a string of cases pursued by the Eastern District of New York in Brooklyn since it handed down a life sentence against Sinaloa Cartel leader Joaquín “Chapo” Guzmán last year.

Currently, the two main overseers of the so-called “war on drugs” during the administration of Mexico’s President Enrique Peña Nieto are being charged for working with the drug cartels. Genaro García Luna, former secretary of public security, arrested last year in Texas, has also pleaded not guilty to charges of receiving millions to protect the Sinaloa Cartel. The case also involves charges against his closest underlings Luis Cárdenas Palomino and Ramón Pequeño García.

The Cienfuegos arrest sent shockwaves through the Mexican ruling elite, with nervous press commentaries calling it “irresponsible” and warning that it “shatters trust in Mexico’s armed forces.”

Cienfuegos was not under any investigation in Mexico, raising suspicions about the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who claims to be leading a campaign against corruption. He has responded to the charges in the US by claiming that “We won’t cover for anybody,” while refusing to remove any of the officials appointed by Cienfuegos, or even those in his circle of confidence like the current chief officer of the secretary of defense, Agustín Radilla.

“I don’t see anyone in the Army happy about this detention,” wrote Mexican reporter Eunice Rendón, who added, “They are the same then and now under [López Obrador’s] ‘Fourth Transformation.’”

The recent cases have gravely tarnished all institutions involved in the “war on drugs,” from the presidencies of Felipe Calderón (2006–2012) and Peña Nieto (2012–2018), to the military and police leaderships, as well as the US administrations that backed the war through the $3.1 billion Merida Initiative since 2007.

As in other countries in the region, chiefly Colombia, drug trafficking has long been exploited by US governments to further Washington’s influence over the region’s security forces and, through this, over domestic politics. “Prior to FY2008,” explains a 2020 report by the US Congress Research Service, “Mexico did not receive large amounts of U.S. security assistance, partially due to Mexican sensitivity about U.S. involvement in the country’s internal affairs.”

The corporate media has largely avoided commenting on the questions the cases raise about the role of the US government itself. García Luna, especially, played a key role in setting up and selling the Merida Initiative to the US and Mexican public.

A December 2007 diplomatic cable released by WikiLeaks indicates that then Deputy Secretary of State John Negroponte was a personal handler of García Luna, helping him “fill in the blanks in preparation for future questioning regarding the Merida Initiative.”

García Luna was also allowed to personally “vet” officials in the Mexican police, a cover used by US agencies to assuage fears of corruption in the Mexican state. An April 2008 cable explains that “unprecedented cooperation … would not be possible without our ability to work with vetted units [by García Luna] supported by USG agencies including DEA and ICE.”

After the killing of several of García Luna’s officials by rival drug cartels in 2008—officials eulogized by the US embassy for their “outstanding work” and “highest professional standards”— an embassy cable expressed “concerns about García Luna’s ability to manage his subordinates.” Nonetheless, in October 2009, the US ambassador said García Luna, who had just quintupled the size of the federal police with the help of US aid, would be a “key player” in reaching “new levels of practical cooperation in two of the country’s most important institutions.”