ALL HIGH TECH BILLIONAIRES ARE DEMOCRAT. ALL HIGH TECH BILLIONIARES ARE FOR BIDEN'S AMNESTY AND NO LEGAL NEED APPLY!

The Republican Plan to Water Down Antitrust Reform

A sweeping package of legislation to take on Big Tech just moved forward in the House. There’s a trap waiting for it in the Senate.

On Thursday, after a marathon 29-hour mark-up session, the House Judiciary Committee advanced, with substantial bipartisan support, the most sweeping package of antitrust legislation in decades. The suite of six bills would funnel more funds into the government’s antitrust enforcement agencies, prevent tech giants from acquiring potential rivals, prohibit such firms from giving their own products and services preference over their competitors on their platforms, and give federal regulators the authority to sue to break up behemoths like Google and Amazon when their role as an operator platform creates an “irreconcilable” conflict of interest with their other lines of business.

That this phalanx of potent reform legislation moved forward at all would have been politically unthinkable as recently as a year ago. And it did so despite fierce opposition from an army of industry lobbyists and tech industry-funded research and advocacy groups—some left of center, like the Progressive Policy Institute, others right of center, like the Alliance on Antitrust. Apple sent letters to committee leaders warning that the bills, if turned into law, would thwart the company from offering privacy and security protections to users. CEO Tim Cook, according to the New

York Times, called House Speaker Nancy

Pelosi to try and sway her from backing

the effort.

While final passage is not assured—a number of House Democrats from tech-heavy California districts oppose the bills—Pelosi, who also represents such a district in San Francisco, has indicated a commitment to getting them through the chamber, and her track record of successfully shepherding legislation is legendary. “We are not going to ignore the consolidation that has happened and the concern that exists on both sides of the aisle,” she said.

As with most legislation nowadays, though, the biggest obstacle will be the Senate, where the filibuster, likely to continue in its present form, will mean that 60 votes will be needed for the legislation to make it to President Joe Biden’s desk. Still, several Senate Republicans, such as Josh Hawley of Missouri and Ted Cruz of Texas, have been leading the rhetorical fight against tech monopolies, which they accuse of shutting down conservative speech, among other sins. With anti-monopoly becoming a rallying point among the conservative base voters, more GOP senators might be tempted to jump on board.

In situations like this, a classic Washington maneuver is to offer up legislation that seems to address a problem, but actually doesn’t, in order to give on-the-fence lawmakers a way of looking like they are doing something about it when, in fact, they are not. Two GOP senators have already done precisely that. Mike Lee, of Utah, and Chuck Grassley, of Iowa, might have seemed to join the growing cohort of anti-monopoly lawmakers in Congress last week when they introduced the TEAM Act to Reform Antitrust Law. The TEAM acronym stands for “Tougher Enforcement Against Monopolies.” “Anticompetitive and monopolistic business practices hurt innovation and consumers,” Grassley said in a press release announcing the legislation. “This bill streamlines and strengthens antitrust enforcement and holds bad actors accountable for their actions while preserving a free market.”

But according to a number of antitrust experts, the measure would do the opposite. Under the Orwellian guise of claiming to ramp up antitrust enforcement, critics say, the bill would weaken America’s antitrust regime by taking away the Federal Trade Commission’s enforcement authority and enshrining into law the very approach that led to the crisis reformers are trying to address. “This is very much a pro-monopoly bill,” Sandeep Vaheesan, a former Federal Trade Commission official who is now the legal director for the Open Markets Institute, an anti-monopoly think tank, told me. “The Tougher Enforcement Against Monopolies title is false advertising.”

The Lee-Grassley legislation would primarily do two things. It would consolidate all antitrust enforcement to just one agency—the Department of Justice—and would codify into federal law the consumer welfare standard, the theory espoused by the late jurist Robert Bork in the 1970s that antitrust law should focus narrowly on the effects on consumers and not on the potential harm that a merger or a corporation’s conduct may have on competitors. In fact, before this theory was adopted by both the courts and the enforcement agencies in the 1980s, antitrust was widely understood as having a much broader design—to engineer a socially just economy by preventing dangerous concentrations of economic and political power.

Indeed, the hands-off approach initiated by the Reagan administration—and maintained by its successors—has induced a cascade of ever-increasing mergers and acquisitions, resulting in the economy becoming more consolidated than at any point since the original Gilded Age. Four airlines control more than 85 percent of all domestic air travel, three chains own 99 percent of all pharmacies, and one tech giant accounts for more than half of all e-commerce. And the fact that the national economy is now dominated by fewer and fewer companies, in fewer and fewer places, has led to a clustering of wealth and opportunity in just a handful of coastal cities while most of middle America has been hung out to dry, creating unprecedented new levels of regional inequality.

A Senate staffer who worked on the drafting of the bill told me that eliminating the dual-agency construct was “a way of making our antitrust enforcement system work better.” The frustration, the source said, was that, in recent years, there has been bureaucratic infighting between the agencies over who gets to do what case. At the same time, the FTC, they argued, has been unable to take on cases when there is turnover among commissioners. “At the end of the Obama administration, there were like two commissioners up there,” they said. “So, they are really hamstrung with reviewing different cases and mergers. We think this is a way to make it all work better, to put it under one roof at the DOJ.”

That provision is also supported by conservative policy advocates who are challenging the expanding appetite among lawmakers to ramp up antitrust. “I think it makes a lot of sense to consolidate agency enforcement. The overlapping agency enforcement has been a big problem, both for efficiency and for merger review and enforcement,” Ashley Baker, who runs the Alliance on Antitrust, told me.

Few people would argue that the current dual-agency system has worked smoothly, Vaheesan said. But turning the FTC strictly into a consumer protection agency, he added, would do little to confront the oligopolies that now dominate the American economy. In fact, it would eviscerate the original doctrine that guided the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914—that antitrust enforcement itself should never become concentrated by one government entity, lest it becomes captured, as often happens, by the people it is supposed to be regulating. Moreover, as Vaheesan has previously pointed out in these pages, the FTC has statutory power for fighting monopolies that go far beyond those of the Department of Justice or other antitrust regulators.

Lee, for his part, has been a skeptic of the dual-agency construct for years, long before Biden named the anti-monopoly crusader Lina Khan to chair the FTC. In 2019, the Utah Senator, whose father was the Solicitor General under Reagan, questioned the arrangement in which the FTC would investigate Facebook, and the DOJ would probe Google. “Given the similarity in competition issues involved, divvying up these investigations is sure to waste resources, split valuable expertise across the agencies, and likely result in divergent antitrust enforcement,” he said at the time.

Antitrust reformers also question the provision to codify the consumer welfare standard into law. “This is exactly the wrong direction,” Alex Harman, a competition policy advocate at Public Citizen, told me. “We are trying to make the case that the harm of monopoly power is more than just price. Sometimes, price isn’t an issue at all, like with the tech companies. There’s harm to communities, harm to small businesses, harm to workers, harm to consumers in the sense that there’s a lack of choice. Lack of innovation. Harm to democracy as these companies have become the richest companies on the planet. They’re able to spend huge quantities of money influencing the government through political contributions and lobbying expenditures. Amazon and Facebook are the two companies that spend the most amount of money on corporate lobbying, each. It’s craziness. To reaffirm that the only thing that matters here is consumer price is tone deaf.”

According to both the Senate staffer and Baker, the language of the bill “clarifies” that the consumer welfare standard applies to more than just price.

“When courts are looking at whether something is anticompetitive, they need to be looking at what are the effects on consumers,” the staffer told me. “But it’s also making clear that that’s not limited to price. It never really has been limited to price. That’s a misnomer that people pass around, largely, I think, because that makes it easier to argue against the consumer welfare standard. But this would put it into law that it is not limited to price. It includes quality, output, innovation, consumer choice, and that’s not an exhaustive list.”

Anti-monopoly advocates argue that even this articulation of the consumer welfare standard would not result in stronger antitrust enforcement.

“The Supreme Court has consistently defined the consumer welfare standard as involving price and output, with sometimes taking into account quality and innovation,” Vaheesan said. “But the problem is that what appears to be a scientific inquiry is actually based on an impossibly subjective standard.” In other words, even something as straightforward as what the effect of a merger will be on prices still relies on supposition and contending speculating experts. And there is also the discrepancy between what the effects on prices will be in the short-term and the long-term. Instead, Vaheesan argued for a return to the bright-line rules that traditionally governed antitrust prior to the 1980s, which strictly prohibited mergers and acquisitions that resulted in high degrees of concentration.

According to Bork’s formulation when he devised the standard, antitrust law was marked by a fundamental contradiction: It was meant to safeguard consumers from higher prices as well as small businesses from behemoths that can squash them. As a consequence, Bork argued, antitrust was allowing small businesses to charge higher prices, thereby hurting the very consumers it was intended to help. Hence the title of his famous tome, The Antitrust Paradox. The solution, then, he said, was to only look at the effect of a merger or acquisition on “consumer welfare” and not other factors. In fact, concentration, he would say, often led to efficiencies that led to lower prices and thus benefited consumers.

Bork’s view has been the modus operandi of both the courts and antitrust enforcement practitioners since—which has led to high levels of concentration and which is one of the reasons why critics of the bill say it would do little to fight monopolies. “The bill doubles down on the existing approach to antitrust,” Vaheesan said.

“[Senator] Lee’s a smart guy,” Vaheesan added. “He sees there’s a growing movement among Democrats and some Republicans to crack down on concentration. But he’s really committed to the status quo. He doesn’t want things to change. He’s savvy enough to realize he has to sing a somewhat different tune now. He can’t just say what he’s been saying for the last five years on antitrust. He needs to offer some concessions.”

Those concessions, presumably, are provisions in the bill to increase merger filing fees and implement a market-share merger presumption, both of which come out of legislation previously introduced by Minnesota Democrat Amy Klobuchar, the chair of the Senate’s antitrust subcommittee. It would also apply to all markets across the economy, not just the tech industry. But perhaps most importantly, it reveals a new strategy on the part of Republicans to dampen anti-monopoly sentiment in Congress and within the GOP base—proposing ideas claiming to crack down on corporate giants but that would, in effect, allow them to continue to monopolize the American economy.

“Our view is that antitrust law is not fundamentally broken,” the Senate staffer told me. “At the same time, obviously based on everything in our bill, we don’t think it’s perfect. We think there’s stuff that can be improved, but we’re not trying to radically upend the antitrust law framework in the country. We just want to make it work better for consumers.”

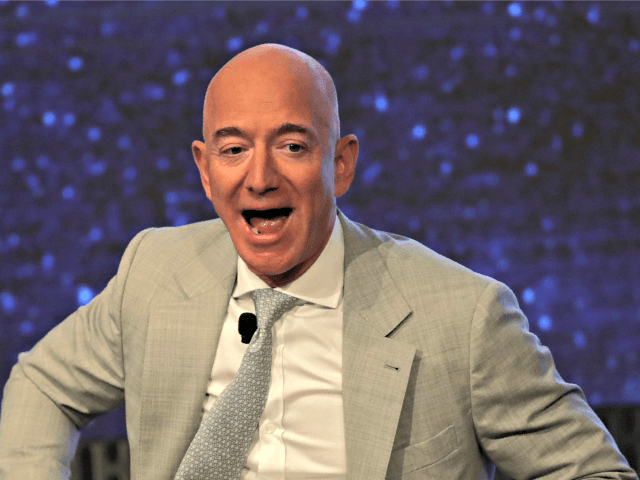

Amazon’s Message to Delivery Drivers: ‘Endorphins Are Your Friend’

Amazon’s Prime Day sale has ended but many delivery drivers are still working extended hours to deliver packages. Before its major annual sale, the internet giant gave drivers tips to “keep in top shape,” and assured them that “endorphins are your friend.”

Motherboard reports that although Amazon’s signature Prime Day sales event has finished, many of the orders placed during the sale are still being delivered. In the UK, Amazon gave delivery drivers a set of five tips for “keeping in top shape” while delivering Prime Day purchases.

The tips included eat breakfast, drink water, take breaks, stay positive, and stop for lunch. However, for many Amazon drivers, these tips are simply not possible. Amazon drivers face extreme pressure from their employers, known as Amazon Delivery Partners, who are in turn paid and evaluated by Amazon.

Essentially, they have to finish their delivery routes as quickly as possible and are often under pressure to break safety rules, traffic laws, and skip legally mandated breaks to hit delivery targets.

“Keep it positive: Endorphins are your friend! Keep them flowing by staying on the move, and striking up a conversation,” one of the driver tips states.

On Facebook forums where Amazon drivers regularly discuss their workdays, drivers joked about Amazon’s tips. “Take your lunch and breaks. Sure, if you want [your dispatcher] on your ass saying you’re 20 or so stops behind,” one Amazon delivery driver in Los Angeles wrote.

An Amazon delivery driver in London who received the flyer told Motherboard: “I don’t take a break. I eat and drink as I go, as I like to get back to see my kids before they go to bed.”

An Amazon delivery driver in Virginia told Motherboard: “As for striking up conversations, sometimes customers wanna chat, but we always kinda respond like, ‘Haha that’s great—anyway we gotta go.'”

An Amazon delivery driver in North Carolina who quit earlier this year told Motherboard: “I got a lot of routes in the mountains, so I opened a black trash bag in the back of the van and peed over that. I’m dehydrated and exhausted, and that’s led to my resignation. People are killing their bodies to keep up with the demand, and it has to stop.”

Read more at Motherboard here.

Lucas Nolan is a reporter for Breitbart News covering issues of free speech and online censorship. Follow him on Twitter @LucasNolan or contact via secure email at the address lucasnolan@protonmail.com

No comments:

Post a Comment