The Price of a Bloomberg Nomination Is Too Damn High

This is what plutocracy looks like. Photo: Melissa Gerrits/Getty Images

In the wake of Donald Trump’s 2016 victory, Democrats made a concerted effort to fortify their party’s pro-democracy and anti-corruption bona fides. Their opening salvo in the 2018 midterm campaign was the “Better Deal Agenda,” a suite of policies aimed at combating concentrated corporate power and the “armies of lobbyists” that had given big money a “stranglehold on Washington.” The first bill Nancy Pelosi’s majority passed upon taking the House was a package of voting-rights expansions and campaign-finance reforms designed to ensure that our “government works for the public interest, the people’s interest, not the special interest.” And throughout the Trump era, Democrats have hammered the president for helping the superrich translate their economic power into the political variety.

But the party may let a megabillionaire openly purchase its 2020 nomination anyway.

Mike Bloomberg has offered blue America a Faustian bargain: Forfeit all credibility on the issues of money in politics and democratic reform, and he will spend whatever it takes to make the bad man in the White House go away. The market for what Bloomberg is selling is large and growing, thanks in no small part to the $300 million he’s already spent advertising it. Many rank-and-file Democrats — like so many disillusioned voters in democracies the world over — like the idea of hiring a no-nonsense, post-political businessman to fix their broken government (just, you know, a less ostentatiously racist one than America’s current CEO). Meanwhile, many Democratic elites see Bloomberg as a (slightly unsavory) savior who can single-handedly stop the party from nominating a supposedly unelectable socialist, provide its vulnerable first-term suburban House members with an ideal standard-bearer, and liberate the party from all resource constraints and fundraising headaches as it rides a rising tide of billionaire bucks back into power.

But Democrats would be fools to accept Bloomberg’s indecent proposal.

I’m not an anti-big-dollar-donor purist. Removing an increasingly lawless, openly racist president from power is more integral to realizing our nation’s democratic promise than keeping our side’s FEC records pristine (as even Bernie Sanders seems to understand). Bloomberg has said that he’s willing to put his well-heeled campaign operation behind the Democratic nominee this fall, even if that nominee proves to be a self-avowed socialist. If the former mayor is telling the truth — if he is truly willing to choose social democracy over barbarism, and bankroll a Democratic candidate who is openly hostile to the billionaire class — then Democrats should probably take his money and run.

But accepting a plutocrat’s patronage and letting your party serve as a vehicle for him to amass direct, personal power over our government are two very different propositions.

As a political matter, allowing a Wall Street tycoon to win the Democratic nomination by leveraging his personal fortune to outbid all of his rivals (and many state and local Democratic Party organizations) for top-shelf campaign staff, and inundate the airwaves with an unprecedentedly exorbitant blitzkrieg of paid messaging, would deprive Democrats of what has long been their chief electoral asset: the perception that their party is less beholden to the rich than the GOP.

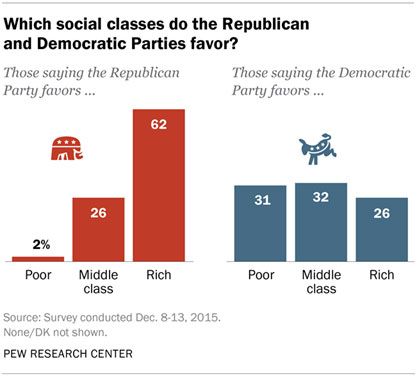

Every presidential election cycle, the American National Election Studies (ANES) survey offers respondents the opportunity to say, in their own words, what they like or dislike about the two major parties and their presidential candidates. When Boston University political scientist Spencer Piston examined the results the 2008 ANES, he found that one of voters’ most commonly cited reasons for liking Barack Obama — and disliking John McCain — was the belief that Democrats cared about the poor (who get less than they deserve from our government), while Republicans cared too much about the rich (who already get more than their fair share). Across the voters’ responses, Piston found 263 mentions of “the rich” or synonyms for the rich. Only six of those mentions were favorable.

In subsequent research, Piston found that this “resentment of the rich” played a key role in Obama’s 2012 reelection. Using data from the ANES 2013 “recontact survey,” he demonstrated that believing the wealthy have more than they deserve strongly correlated with support for Obama, even when controlling for partisanship, ideology, attitudes toward income inequality, and demographic characteristics. Which is to say, a white “moderate” swing voter who evinced strong resentment of the rich was significantly more likely to vote for the incumbent Democrat than one who lacked such class animosity. All told, resentment of the rich was “associated with an increase in the probability of voting for Obama of 11 percentage points.”

Many other surveys have confirmed that Republicans pay an electoral penalty for their perceived fealty to the wealthy. It is hard to believe that Democrats could nominate a Wall Street tycoon without eroding this vital source of partisan advantage. Hillary Clinton’s mere perceived coziness with such fat cats, combined with her decision to largely elide class-based appeals in paid messaging, was (ostensibly) sufficient to undermine the Democrats’ populist edge four years ago; according to Piston’s analysis, “resentment of the rich” ceased to be predictive of partisan preference in 2016.

Photo: PEW Research Center

Some may regard this as a price worth paying. Given the Democrats’ growing reliance on affluent suburbanites, and the GOP’s growing margins with white non-college-educated voters, you might regard the Donkey Party’s fading populist credibility as a fait accompli. But nominating Bloomberg wouldn’t just confirm the right’s caricature of liberal hypocrisy on the small matter of creeping plutocracy; it would also make Democrats look like raging hypocrites on just about every major article of the party’s putative faith.

In the Trump era, Democrats have mined grassroots activism and moral purpose from the Me Too movement. The party’s 2018 triumph owed a great deal to college-educated women who’d been radicalized by the pussy-grabber-in-chief’s election, and mobilized by the realization that the routine misogyny that had shadowed their working lives was a political problem with a political solution. What message would the Democratic Party be sending to that constituency if they nominated a man with this record:

From 1996 to 1997, four women filed sexual-harassment or discrimination suits against Bloomberg the company. One of the suits included the following allegation: When Sekiko Sakai Garrison, a sales representative at the company, told Mike Bloomberg she was pregnant, he replied, “Kill it!” (Bloomberg went on, she alleged, to mutter, “Great, No. 16”—a reference, her complaint said, to the 16 women at the company who were then pregnant.) To these allegations, Garrison added another one: Even prior to her pregnancy, she claimed, Bloomberg had antagonized her by making disparaging comments about her appearance and sexual desirability. “What, is the guy dumb and blind?” he is alleged to have said upon seeing her wearing an engagement ring. “What the hell is he marrying you for?”Bloomberg denied having made those comments, claiming that he passed a lie-detector test validating the denial but declining to release the results. (He also reportedly left Garrison a voicemail upon hearing that she’d been upset by the comments about her pregnancy: “I didn’t say it, but if I said it, I didn’t mean it.”) What Bloomberg reportedly did concede is that he had said of Garrison and other women, “I’d do her.” In making the concession, however, he insisted that he had believed that to “do” someone meant merely “to have a personal relationship” with them.That suit was settled in 2000; its terms were not disclosed. Other suits made similar claims. In a 1998 filing, Mary Ann Olszewski reported that “male employees from Mr. Bloomberg on down” routinely belittled women at the company—a pattern of harassment, she said, that culminated in her being raped in a Chicago hotel room by a Bloomberg executive who was also her direct superior. The case was dismissed (not, apparently, on its merits, but rather because Olszewski’s attorney had missed the deadlines to respond to a motion to end the case). Before it was, though, in a deposition relating to the suit, Bloomberg testified that he wouldn’t consider Olszewski’s rape allegation to be genuine unless there were “an unimpeachable third-party witness” to corroborate her claims. (Asked by a lawyer how such a person might happen to witness a rape, Bloomberg replied, “There are times when three people are together.”)

Some details of Bloomberg’s mistreatment of his female subordinates remain disputed, with the allegations sheltered from public view by nondisclosure agreements that the candidate refuses to waive. But there is no debate about whether Bloomberg routinely subjected the women at his companies to misogynistic “banter” (one of the mogul’s favorite workplace jokes: “If women wanted to be appreciated for their brains, they’d go to the library instead of Bloomingdale’s”). The billionaire acknowledged and apologized for this habit shortly after launching his campaign.

Democrats fancy themselves the party of civil rights and racial justice. Conservatives counter that liberals’ avowed anti-racism is largely opportunistic, rooted less in concern for the well-being of minority groups than the utility of the “race card” as a political weapon. How much harder will it be for Democrats to rebut that (mendacious) charge, if we decide to nominate a man who:

• Argued that the rollback of racially discriminatory housing policies was largely to blame for the 2008 financial crisis.

• Forthrightly championed a method of policing that he proudly described as racially discriminatory, and which a federal judge declared unconstitutional (a fact Trump’s reelection campaign is already eagerly spotlighting).

• Subjected entire Muslim communities to state surveillance on the basis of nothing beyond their religious faith.

If Bloomberg is telling the truth — if Democrats will have his financial backing no matter whom they nominate — why on Earth would the party accept these liabilities? Because they can’t win without Bloomberg’s raw animal magnetism?

Alternatively, if Bloomberg is bluffing to curry favor with Democratic primary voters and would withhold resources if the party nominates a candidate he dislikes, then Democrats cannot trust him with the presidency anyway. The same personal fortune that would free the Democratic Party from cash constraints this fall would also liberate a President Bloomberg from partisan constraints once in office. If the plutocratic president decides to find common ground with a Republican Senate on Social Security cuts, what leverage will the Democratic Party have over “their” White House? The party will always need Bloomberg’s fundraising prowess more than he will need theirs.

Pete Buttigieg, Joe Biden, and Amy Klobuchar are not on my wavelength ideologically. I find much of the former South Bend mayor’s rhetoric vacuous, the former vice-president’s oratory unnervingly incoherent, and the Minnesota senator’s history of abusing her staff unacceptable. But none of them are running campaigns that make an open mockery of our nation’s democratic aspirations, or the Democratic Party’s purported opposition to plutocracy. And none of them could substitute personal wealth for the support of the Democratic coalition upon taking power. The AFL-CIO will have influence over a Klobuchar administration’s labor regulations and NLRB appointments because Amy Klobuchar will need its support when she runs for reelection. The ACLU and Movement for Black Lives will have some voice in a Buttigieg White House because the former small-town mayor will not be able to afford forfeiting the backing of any part of his party’s base. The reason to “vote blue, no matter who” is that you are not just electing a candidate, but a coalition. A Bernie Sanders administration will surely do many important things differently than a Joe Biden one. But they would also do many things similarly, because they will be dependent on the support of almost all of the same constituencies. That won’t necessarily be true of President Bloomberg.

Michael Bloomberg is not a monster. By the standards set by other megabillionaires, he’s probably closer to a saint. While his fellow plutocrats have concentrated their political investments on accelerating the upward redistribution of wealth, Bloomberg has supplied ample resources to combating gun violence, checking Donald Trump’s power, and averting catastrophic climate change. His work on the latter issue has been especially valuable. If he would like to continue making recompense for the uglier aspects of his record by bankrolling the resistance to authoritarian ethno-nationalism in the U.S., Democrats should let him purchase their indulgences. But they must keep their party’s soul out of his price range.