SHE IS A LAWYER! THE TRUTH IS WHAT EVER SHE SAYS IT IS BUT ONLY FOR THAT DAY!

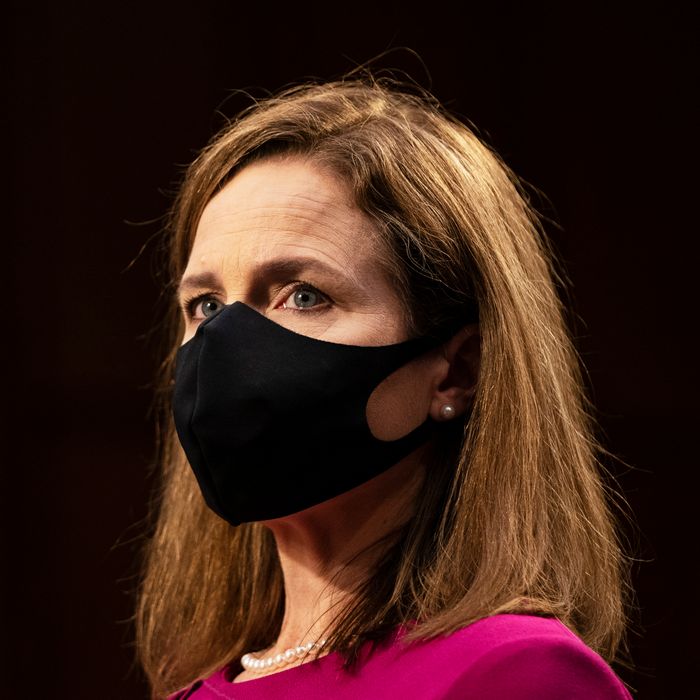

(CNSNews.com) – Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett told the Senate Judiciary Committee on Tuesday that she can and has set aside her Catholic beliefs regarding issues before her.

In an exchange with Chairman Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), Barrett was asked about her Catholic faith and whether she can set aside her religious beliefs when deciding on issues before her.

“I can. I have done that in my time on the 7th Circuit. If I stay on the 7th Circuit, I'll continue to do that. If I'm confirmed I to the Supreme Court, I will do that still,” she said.

Graham also asked her about the Supreme Court decisions that led to the legalization of abortion, same-sex marriage whether she owns a gun, and whether she can fairly decide gun cases, and the Citizens United case.

Barrett said she owns a gun and can fairly decide such cases.

On abortion, Graham asked Barrett if she would listen to both sides if litigation on his bill, which bans abortion on demand after 20 weeks of pregnancy.

Barrett answered: “Of course, I'll do that in every case.”

GRAHAM: Let's talk about the two Supreme Court cases regarding abortion. What are the two leading cases in America regarding abortion?

BARRETT: Most people think of Roe V. Wade, and Casey is the case after Roe that preserved Roe’s central holding but grounded it in a slightly different rationale.

GRAHAM: So what is that rationale?

BARRETT: Rationale is that the state cannot impose an undue burden on a woman's right to terminate a pregnancy.

GRAHAM: Unlike Brown, there are states challenging on the abortion front. There’re states that are going to a fetal heartbeat bill. I have a bill, Judge, that would disallow abortion on demand after 20 weeks, the fifth month of the pregnancy. We're one of seven nations in the entire world that allow abortion on demand at the fifth month. The construct of my bill is because a child is capable of feeling pain in the fifth month, doctors tell us to save the child's life, you have to provide anesthesia if you operate, because they can feel pain. The argument I’m making is if you have to provide anesthesia to save the child’s life, ‘cause they can feel pain, it must be a terrible death to be dismembered by an abortion. That's a theory to protect the unborn at the fifth month. If that litigation comes before you, will you listen to both sides?

BARRETT: Of course, I'll do that in every case.

GRAHAM: So I think 14 states have already passed a version of what I described. So there really is a debate in America still unlike Brown versus Board of Education about the rights of the unborn. That's just one example. So if there is a challenge coming from a state, if a state passes a law and it goes into court where people say this violates Casey, how do you decide that?

BARRETT: Well, it would begin in a district court in a trial court. The trial court would make a record. The parties would litigate and fully develop that record in the trial court. Then it would go up to an appeals court that would review that record looking for error, and then again, it would be the same process. Someone would have to seek certiorari at the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court would have to grant it, and at that point it would be the full judicial process. It would be briefs, oral argument, conversations with law clerks in chambers, consultation with colleagues, writing an opinion, really digging down into it. It's not just a vote. You all do that. You all have a policy, and you cast a vote. The judicial process is different.

GRAHAM: Okay. So when it comes to your personal views about this topic, do you own a gun?

BARRETT: We do own a gun.

GRAHAM: Okay. All right. Do you think you could fairly decide a case even though you own a gun?

BARRETT: Yes.

GRAHAM: You're Catholic.

BARRETT: I am.

GRAHAM: We've established that. The tenets of your faith mean a lot to you personally. Is that correct?

BARRETT: That is true.

GRAHAM: You've chosen to raise your family in the Catholic faith, is that correct?BARRETT: That's true.

GRAHAM: Can you set aside whatever Catholic beliefs you have regarding any issue before you?

BARRETT: I can. I have done that in my time on the 7th Circuit. If I stay on the 7th Circuit, I'll continue to do that. If I'm confirmed I to the Supreme Court, I will do that still.

GRAHAM: I would dare say there are personal thoughts on the Supreme Court, and nobody questions whether our liberal friends can set aside their beliefs. There’s No question -- no reason to question yours in my view. So the bottom line here is that there is a process. You fill in the blanks whether it's about guns and Heller, abortion rights. Let's go to Citizens United. To my good friend Senator Whitehouse. Me and you are going to come closer and closer about regulating money, ‘cause I don't know what's going on out there, but I can tell you there’s a lot of money being raised in this campaign. I’d like to know where the hell some of it is coming from, but that's not your problem. Citizens United says what?

BARRETT: Citizens United extends the protection of the First Amendment to corporations who are engaged in political speech.

GRAHAM: So if Congress wanted to revisit that and somebody challenged it under Citizens United that Congress went too far, what would you do? How would the process work?

BARRETT: Well, it would be the same process that I've been describing. First, somebody would have to challenge the law in a case - somebody who wanted to spend the money in a political campaign. It would wind its way up, and judges would decide it after briefs and oral argument and consultation with colleagues and the process of opinion writing.

GRAHAM: Same-sex marriage. What’s the case that established same-sex marriage as the law of the land.

BARRETT: Obergefell.

GRAHAM: Okay, if there is a state that tried to outlaw marriage, and there’s litigation, would it follow the same process?BARRETT: It would, and one thing I’ve neglected to say before that’s occurring to me now is that not only would someone have to challenge that statute, and somebody -- if they outlawed same-sex marriage, there would have to be a case challenging it. And for the Supreme Court to take it up, you’d have to have lower courts going along and saying we're going to flout Obergefell, and the most likely result would be that lower courts who are bound by Obergefell would shut such a lawsuit down, and it wouldn't make its way up to the Supreme Court, but If it did it would be the same process I’ve described.

Amy Coney Barrett’s Judicial Neutrality Is a Political Fiction

Shortly after Ruth Bader Ginsburg exited this mortal plane (and before her body entered the earth), Mitch McConnell announced that his party would nominate and confirm her replacement to the Supreme Court.

The Senate majority leader justified his hypocritical stance by citing the GOP’s obligation to the “American people” who “reelected our majority in 2016 and expanded it in 2018 because we pledged to work with President Trump and support his agenda, particularly his outstanding appointments to the federal judiciary.” Of course, the “American people” did not uniformly support Republicans in those elections, let alone for that reason. The people McConnell referenced are strong GOP partisans.

In the weeks since Ginsburg’s passing, Republicans have reiterated — through words and deeds — that they consider the appointment of Trump’s Supreme Court nominee, Amy Coney Barrett, to be a partisan goal of the highest importance. The GOP is so committed to her confirmation it has prioritized it over economic relief in the midst of a brutal recession. It’s so committed to it that Chuck Grassley and Lindsey Graham — 87 and 65 years old, respectively — have refused to take COVID-19 tests despite being exposed to infected individuals out of an apparent preference for risking the spread of a pandemic disease over risking positive tests that would force the GOP senators into quarantine, cost the GOP its majority on the Senate Judiciary Committee, and thus imperil Barrett’s nomination.

And yet: During the first day of her confirmation hearing, Barrett revealed that all of this was for naught. As the Supreme Court nominee explained to the Senate in her opening statement, her confirmation would have no predictable influence on public policy, nor would it advantage any particular ideological movement. If confirmed, all she would do is enforce existing law, nothing more, nothing less:

Courts have a vital responsibility to enforce the rule of law, which is critical to a free society. But courts are not designed to solve every problem or right every wrong in our public life. The policy decisions and value judgments of government must be made by the political branches elected by and accountable to the People. The public should not expect courts to do so, and courts should not try … I believe Americans of all backgrounds deserve an independent Supreme Court that interprets our Constitution and laws as they are written. And I believe I can serve my country by playing that role.

Of course, these words did not actually cause the committee’s conservatives to dissolve into spasms of despair. In the minds of Republicans, Barrett’s statement didn’t actually contradict the notion that her confirmation had profound ideological stakes. After all, honoring the objective meaning of the “Constitution and laws as they are written” will advance conservative goals — because the conservative movement is the one true upholder of our Republic’s founding principles.

If you read Barrett’s statement in this light — which is to say, if you presume that the entire Republican leadership and base are not fools who tragically mistook the significance of her nomination — then her claim to neutrality is actually more partisan than a frank admission of ideological commitment.

Barrett could acknowledge that a singular, objective interpretation of written language is beyond the capacity of the human mind and that — when in doubt — she errs on the side of a particular jurisprudential tradition that is closely affiliated with a particular ideological movement. Instead, she implicitly asserts something far more audacious: that her movement’s jurisprudence is tantamount to rule of law itself.

Barrett is hardly unique in selling herself as a disinterested umpire. Justices both left and right have offered the Senate similar avowals of judicial modesty. But as a self-described “originalist,” Trump’s nominee puts exceptional weight on her supposedly disinterested adherence to the “original public meaning” of the U.S. Constitution. Yet “originalism” is less a humble method for settling constitutional disputes than a parlor trick for recasting the conservative movement’s unpopular agenda as the minimum demanded by constitutionality.

Constitutional scholars have already made versions of this argument with a level of rigor I can’t approximate. But what I can do — in my throughly ideologically interested way — is give you three quick reasons why originalism is a sham:

(1) The meaning of constitutional language was ambiguous at the time of America’s founding (and even if it wasn’t, the Supreme Court is a collection of lawyers, not a panel of eminent 18th-century historians)

A former English major, Barrett knows that written language does not often have a single, unambiguous meaning. And the words of our founding document are no exception. The Constitution is replete with capacious abstractions like “the general welfare of the United States” and inherently subjective phrases like “necessary and proper” and “unreasonable.” In many instances, the ambiguity of these phrases was the apparent intention: The Founders effectively postponed the final settlement of their internal disputes by concealing their disagreements in imprecise diction. Thus, immediately after ratification, Hamilton informed Jefferson and Madison that their narrow interpretation of the “necessary and proper clause” depended on an ignorant reading of the word necessary, which “often means no more than needful, requisite, incidental, useful, or conducive to.”

The very concept of “original public meaning” — which posits that intelligent, involved members of a polity will have little trouble agreeing on the meaning of a given phrase at a specific point in time — is belied by the lived experience of our era, in which well-educated, highly engaged Democrats and Republicans get into heated semantic disputes on a near-daily basis. (Recently, such partisans have struggled to achieve consensus on the “original public meaning” of things Mitch McConnell said just four years ago.)

But even if we stipulate that there was a predominant, public interpretation of the Constitution’s thorniest phrases in 1788, why exactly would nine lawyers in robes have the authority to determine it? History is an academic discipline. The difficulty of deriving hard truths about a society from documentary evidence is so profound experts who devote decades of their lives to studying a single time and place can arrive at different answers to that period’s defining questions. When justices claim the authority to determine the unequivocal meaning of a phrase at a given point in history, they are not demonstrating judicial humility but supreme arrogance. The farcical nature of the originalist enterprise was made plain in the 2008 case District of Columbia v. Heller. Then, Justices Antonin Scalia and John Paul Stevens each produced their own historical monograph on the Second Amendment’s contemporary meaning, which arrived at antithetical conclusions that just so happened to line up perfectly with each jurist’s ideological tendency. The opinions nevertheless had one thing in common: Both were poorly regarded by actual historians.

(2) Originalism is not a neutral standard

Originalism isn’t bereft of intuitive appeal. Given the subjective nature of linguistic interpretation — and the natural inclination of human judges to resolve ambiguity in ideologically convenient ways — judicial review poses a clear threat to democracy unless it is bound by some external standard. And originalism purports to offer just that.

And yet beyond the inherent ambiguity of the Constitution’s original public meaning, and the unfitness of judges to ascertain it, there is another problem with the standard originalism offers: It is an arbitrary principle that plainly advantages conservatives over liberals.

There is no objective answer to the question of whether one should interpret legal texts on the basis of contemporary or historical meaning. And one cannot derive an answer to that fundamental question from the text of the Constitution itself. To the contrary, the fact that the founders littered their document with ambiguous phrases — without providing any glossary — suggests that they were none too concerned with ensuring that future generations would adhere to their precise, contemporary intentions. These people were not stupid. They understood that language evolves over time and that words can have multiple meanings. And yet they left their document ambiguous anyway. Further, some of the Founders forthrightly advocated for a kind of living constitutionalism, with Madison arguing by the 1790s that the meaning of the Constitution evolved with public opinion.

So originalism cannot justify itself as a neutral approach to jurisprudence on the basis of its own principles. And the doctrine has plainly pro-conservative implications. In contemporary constitutional disputes, defaulting to the intentions of 18th-century aristocrats will advantage reactionaries over progressives more often than not: A movement that prizes tradition and the economic prerogatives of private capital will find the Founders’ contemporary intentions more appealing than a movement that favors social progress and economic equality. This would be true even if originalist conservatives actually applied their methods with unerring consistency. Which they don’t:

(3) No one actually wants the U.S. government to adhere to the Constitution’s original meaning

Even Republicans don’t have the stomach to outsource judgment on all modern constitutional questions to the slaveholding elite of a preindustrial, post-colonial backwater. As Dean of Berkeley Law Erwin Chemerinsky has observed, a ruthless adherence to text and history would require forfeiting judicial protection of “liberties such as the right to marry, the right to procreate, the right to custody of one’s children, the right to keep the family together, the right of parents to control the upbringing of their children, the right to purchase and use contraceptives, the right to abortion, [and] the right to refuse medical care,” none of which are guaranteed by the Constitution.

Amy Coney Barrett herself has acknowledged the undesirability of applying originalism indiscriminately, noting in 2016, “Adherence to originalism arguably requires, for example, the dismantling of the administrative state, the invalidation of paper money, and the reversal of Brown v. Board of Education,” and other institutions that “no serious person would propose to undo,” even if they lack constitutional grounding. Barrett’s proposed solution to this conundrum is for courts to simply avoid ruling on cases where originalism would dictate socially unthinkable overturnings of precedent; she wrote in 2017 that “discretionary jurisdiction generally permits [the Court] to choose which questions it wants to answer.”

But this expedient degrades originalism’s claim to neutrality. If an originalist Supreme Court can apply its doctrine opportunistically — taking only those cases in which its “neutral” juridical method will yield outcomes acceptable to a “serious” person (as they define that adjective) — then originalism isn’t much of a binding restriction on judicial discretion.

What’s more, Barrett’s concession tacitly betrays awareness of a critical fact that originalists love to elide when speaking for a lay audience: Amending the Constitution has become so phenomenally difficult it’s not at all clear that the American people could promptly replace an overturned Brown v. Board of Education with an amendment forbidding school segregation, despite overwhelming popular support for that Supreme Court decision. Originalists like to portray their judicial approach as highly democratic, since they purport to defer to the letter of a democratically enacted Constitution. But once one stipulates that the demos is manifestly no longer capable of passing constitutional amendments with regularity, it becomes clear that the originalist practice of striking down democratically elected laws in deference to the letter of a centuries-old document is profoundly anti-democratic.

Of course, in real life, “originalist” Supreme Court justices haven’t just applied their method opportunistically by selecting cases in which originalism will produce a favored outcome; they’ve also simply declined to abide by their method when they feel like it. On Monday, Barrett named Antonin Scalia as her guiding light on judicial philosophy. But as Georgia State University Law professor Eric J. Segall notes, Scalia voted “for broad rules limiting congressional power to enact campaign finance reform, to commandeer state legislatures and executives to help implement federal law, and to allow lawsuits against the states for money damages by citizens of other states” without “justifying these broad rules from a textual or historical perspective,” presumably because they have no textual or historical basis.

In sum: Amy Coney Barrett’s originalism does not work as a method of safeguarding democracy against an activist, ideologically motivated judiciary. It does, however, function quite well as a means of obscuring a far-right movement’s efforts to impose its unpopular agenda by judicial fiat.

Sen. Cruz: 'Who in Their Right Mind Would Want the USA Ruled by 5 Unelected Lawyers Wearing Black Robes?'

(CNSNews.com) - "Democrats and Republicans have fundamentally different visions of the court, of what the Supreme Court is supposed to do, what its function is," Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) told the Senate Judiciary Committee on Monday, as the confirmation hearing for Judge Amy Coney Barrett got underway.

"Democratic senators view the court as their super-legislature, as a policy-making body, as a body that will decree outcomes to the American people," Cruz continued:

That vision of the court is something found nowhere in the Constitution, and it's a curious way to want to run a country even if on any particular policy issue you might happen to agree with wherever a majority of the court is on any given day.

Who in their right mind would want the United States of America ruled by five unelected lawyers wearing black robes?

It's hard to think of a less democratic notion than unelected philosopher Kings with- life tenure decreeing rules for 330 million Americans. That is not, in fact, the court's job. The court's job is to decide cases according to the law and to leave policymaking to the elected legislatures.

Committee Democrats on Monday warned one after another that President Trump nominated Barrett to the Supreme Court to invalidate the Affordable Care Act.

Democrat senators showed photos of constituents with terrible diseases who would be hurt if the Supreme Court declares the law unconstitutional, now that the individual mandate is not in force.

Cruz said the Senate is the right place to have policy arguments over Obamacare. But he also said Democrats should not expect a judicial nominee to promise to implement their policy vision of healthcare.

"That is not a judge's job. That is not the responsibility of a judge," Cruz said:

I don't know what will happen in this particular litigation on healthcare, but I do know that this body should be the one resolving the competing policy questions at issue.

Many of our colleagues talked about pre-existing conditions, and I think they have made a political decision they want this to be the central issue of the confirmation. But remember this -- every single member of the Senate agrees that pre-existing conditions can and should be protected. The end. There is complete unanimity on it.

Now it so happens that there are a number of us on the Republican side that also want to see premiums go down. Obamacare has caused premiums to skyrocket, the average family's premiums have risen over $5,000 a year. Millions of Americans can't afford healthcare because of the policy failures of Obamacare.

Those questions should be resolved in this body, in the elected legislature. It is not a justice's job to do that, it's not the court's job to do that -- it is the elected legislature's job to do that.