There are two well-known themes, or topoi, in classical literature. One concerns the graphic descriptions in Thucydides, Sophocles, and Procopius of plagues—especially the human misery and despair that accompanies outbreaks that killed large numbers. The unknown plague at Athens (430–429 BC) killed one-quarter of the Athenian population during the Peloponnesian War, wrecking the social structure of the city. In 542 AD, during a virulent bubonic plague epidemic, millions perished throughout the Byzantine Empire, crippling and ultimately curtailing the emperor Justinian’s grandiose efforts to restore the Roman Empire by reclaiming its lost provinces in the West.

But just as frequently, we read of groundless mass panics that caused deadly harm. Thucydides’s description of the preparations of the Athenian armada on the eve of the ill-fated expedition to Sicily is a sort of fantastical bookend to the panic he previously described about the real plague. In 415 BC, a sudden public frenzy swept the Athenian demos to rule all of distant Sicily and get rich from promises of wealthy allies. Sicily was billed as a prequel to a Mediterranean-wide Athenian empire—at least until the money and the allies proved almost nonexistent and the scheme unworkable. Eventually, some 40,0000 Athenian and allied lives were lost in utter defeat.

In the United States, the collapse of the stock market and banks in 1893 and 1929 altered American life for generations, in part driven by panicked selling. One of cinema’s most dramatic scenes is the run on the Bailey Building and Loan in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life that threatens to turn idyllic Bedford Falls into a Potterville slum. I remember as a boy stomping on June bugs all summer long in 1962 to prevent their supposedly deadly contagion that was supposedly sweeping the nation—aping the behavior of those delusional at Athens who drew maps in the sand of Sicily, hooked on the fantasy of the riches to come from the extravagant 415 BC expedition.

In our current hours of COVID-19 despair, we must fight both the virus and the panic that the disease instills, given that the two can be equally deadly. All sorts of scary statistics about the coronavirus infection and lethality rates are being publicized, often to show contrasts with annual influenza strains and other viral epidemics. Some make the legitimate point that if the coronavirus has a lethality rate of over 1 percent to 3 percent in the United States, then perhaps 97 percent to 99 percent of those infected will survive the illness, albeit with varying degrees of seriousness. And for the vast majority of Americans under 50, it may be that 99 percent will recover from infection, in contrast with almost every known “pandemic” in history.

Others, more pessimistic—or perhaps realistic—retort that such an apparently low lethality rate shouldn’t be cause for relief. After all, COVID-19 will likely remain 10 to 20 times more lethal than annual influenzas (with their 0.01 percent to 0.02 percent death rates). Thus, in theory, it could kill not merely 30,000 to 60,000 of some 60 million infected Americans per year, as does an average flu, but rather 300,000 to 600,000, or even double that number. All too possible again.

But the problem with all such educated guesses is that we simply don’t have hard data, at least not yet. If we assume that around 43 million Americans got the flu in the 2018–2019 season and 61,000 died (for a lethality rate, say, of 0.14 percent), that figure is arrived at by the more exact numbers of known deaths—determined by data from given hospitalizations and coroner reports, and past calibrations and experience.

Again, annual flu death rates are still not predicated on the actual number of known flu cases—given that the vast majority of Americans don’t visit the hospital for treatment (less than 2 percent, in most years). There is little way—other than through modeling, albeit often sophisticated and time-tried over years, and working backward from known fatalities due to the flu—to learn the number of flu cases necessary to determine a lethality rate. Of course, yearly flu strains also vary widely in death and hospitalization rates and models reflect differing lethality rates.

In contrast, most of the studies that provide statistics for the current coronavirus so far are based both on known deaths and a limited number of known cases. The former number is apparently arrived at from autopsies—in extremis treatment, testing, or coroner reports—and the latter data either by hospitalization, medical treatment, or testing. The result is that we legitimately assume that lots of coronavirus cases go unreported and untested, and thus that the likely death rate could be far lower than we imagine.

So, whereas it’s a good guess that the annual flu kills far fewer of those infected than does the coronavirus, we’re still basing those assumptions without any exact idea of how many Americans actually catch the flu every year—and thus, without certainty, that the flu is as proverbially nonlethal as assumed. Yet for COVID-19, currently we rely on pretty accurate known numbers on both ends when we arrive at a high rate of lethality that is likely exaggerated.

Pessimists point to Italy, where last week almost 7 percent of those infected had died. Optimists, meantime, note recent developments in South Korea, where the death toll dipped to less than 1 percent of known cases. But every country will be as different as they are with the flu. The percentages who die from influenza and related pneumonia, for example, in Saudi Arabia are over 16 times higher per 1,000 cases than in Finland.

From what we know, a nation’s prompt embrace of travel bans, quarantines, and public-health readiness matters a great deal. So do the average age of the population in particular areas; the quality and availability of existing health care; the degree to which a country rapidly stopped direct flights and travel from infectious areas; the percentages of the population who are smokers or engage in unhealthy behaviors, whether a country had hosted a large number of Chinese tourists, expatriates, or workers with likely greater odds of exposure in the early weeks of the outbreak; and, more controversially, perhaps even the relative temperature and weather conditions of particular infectious regions.

When we put all these diverse criteria together, we are left only with likely parameters, not known facts, other than the conventional wisdom that the vast majority of Americans will likely recover from the infection in the coming days or weeks. So far, we seem to believe that less than four in 1,000 will likely die of those infected younger than age 40. Likewise, coronavirus lethality rates are weighed by much higher deaths of those above age 65, but especially above 80 (nearly 15 percent)—and not just to advanced age alone, but comorbidity from heart diseases, cancer, diabetes, and other chronic illnesses. For the general public, when we talk about supposed degrees of lethality, and then apply those numbers to the population under 40 or 50, the optimistic absolutes that 99 percent will likely recover are seen as more relevant than scary comparisons that far, far more—likely 99.8 percent—will survive the flu. Is that a legitimate concern? Bees and wasps kill about 10 times more people per year than do spiders. Does that mean we should fear walking among pollenating hives (our 40-acre almond farm has about 80 of them), at least far more so than fixing pipes under the house in the spider-infested dark? Or, not at all—given that spiders kill six Americans per year and bees and wasps ten times more so, adding up to about 60 fatalities out of some 2.9 million yearly deaths in the U.S.? The point is one of perception: to what degree do we inadvertently panic the population and wreck the economy by driving home the fact that a possible 98 percent to 99 percent survival rate still means thousands more dead than a conjectured 99.8 percent survival rate?

With new draconian measures of containment, we are entering the realm of cost-benefit analyses, given that for every drastic action there is an equally radical reaction—calibrated by everything from physical and mental health issues to economic, financial, security, legal, and political upheavals. Whether we like it or not, the current sweeping measures to curb the virus come at a huge cost—and the tab isn’t just financial or economic, as is sometimes alleged, by both advocates and critics of quarantines, cancellations, and radical social distancing. It involves health issues as well.

If the country goes into a serious recession or even depression; if trillions of dollars more of investment and liquidity continue to be wiped out while businesses crash and jobs are lost; if millions of unemployed cut back on their scheduled health care; if they increase their use of drugs, alcohol, or tobacco, and get less exercise and suffer depression holed up in their homes or must borrow or scramble to find daycare for their school-age children; if they even contemplate suicide—then the human toll spikes in concrete terms of life and death. In the long term, arming ourselves against the virus could be as serious as the virus itself, though to suggest that in these dark days of plague is heresy.

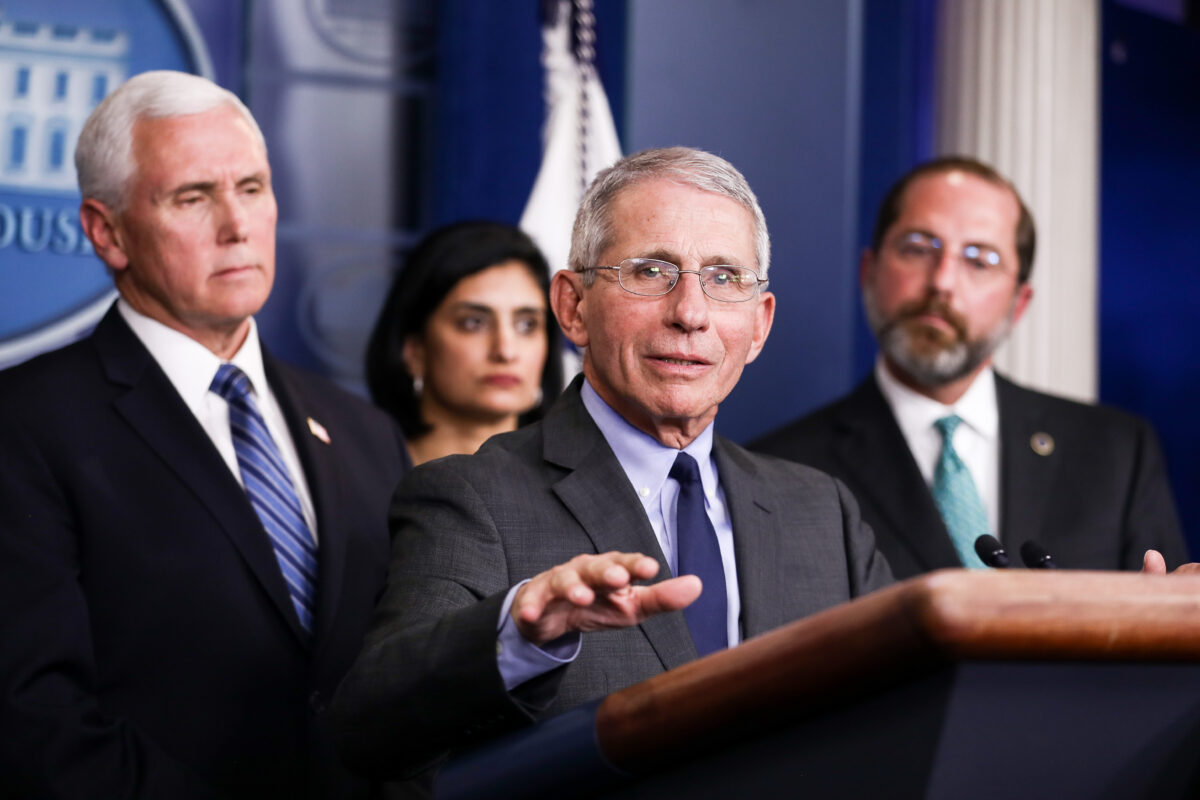

It’s easy to criticize decisions, speeches, news conferences, or commentaries of our policymakers. Mistakes abound and are evident; wise choices are rarely recognized and appreciated. But every tough decision made about the pandemic hinges on finding some perfect, but largely unknown, mean to limit impoverishment, illness, and death. We have relatively recent examples both of failures of doing too much and of too little.

In 1976, also an election year, the country overreacted to the threat of the swine flu, when the press and “experts” warned of a likely return of a 1918 Spanish flu epidemic that this time around could kill “500,000 Americans” and infect “

50 million to 60 million.” By early 1977, Americans were panicked and ready for mass inoculations of a rushed and unproven vaccination. Some 45 million were vaccinated; many had adverse, but limited, reactions, and about 450 reportedly ended up with crippling Guillain-Barré syndrome. The current popular creed that critical vaccinations are dangerous grew in part from the well-publicized 1976 mishap—with unfortunate, and in some cases lethal, consequences in convincing citizens not to get their necessary flu shots. In the end, there were about 200 cases and one death due to the great swine flu pandemic. I remember as a student at Stanford waiting in a campus line for the vaccination, then driving home for spring break and ending up in bed with a bad reaction to the shot.

In 2009, the U.S. was probably too lax in not issuing travel restrictions following rapid spread of the H1N1 swine flu that this time really was virally similar to the agent of the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. The border with Mexico, where the contagion probably began, was never really closed. For months, no national alarm was sounded. Even today, we still don’t know how many were infected or died, given overlaps with other strains of annual flu, early lax reporting and monitoring, and general public nonchalance. Later government guesses of infection ranged from

43 million to 89 million cases and deaths between

8,870 and 18,300. Children were especially vulnerable; perhaps more than 1,000 died. Are we then to think that, either by act of commission or omission, knowingly or unknowingly, a decision was made that the economic vitality of the country was more critical to the nation’s health than the real chance (in retrospect) of the H1N1 virus infecting, say, 50 million Americans, and killing perhaps 12,000, including 1,000 children?

The point isn’t to blame Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, or Barack Obama for their responses, but to realize that what we are first told about an epidemic—even from “experts” armed with “data”—is not always accurate and will likely be later radically readjusted.

Last week, Ohio governor Mike DeWine, in heartfelt worry and with understandable concern,

tweeted a statement from his state Director of Health: “I know it is hard to understand

#COVID19 since we can’t see it, but we know that 1 percent of our population is carrying this virus today—that’s over 100,000 people.” In translation, that would mean that DeWine and the director already also “know” that somewhere between 1,000 to 2,500 elderly Ohioans of that infected 100,000 right now, at a minimum (if the case load stays at the static figure of 100,000 and the current death ratios are accurate), are infected and will die in the next one to three weeks. At the time of the governor’s disclosure, there were five known cases of corona virus reported in the state.

Let us hope that the governor proves to be sober and judicious in preventing by these dire warnings such mass death in the next two weeks, but also let us understand that by making such a declaration of fact about 100,000 existing cases (“we know”), DeWine took a risk and is also terrifying 2 million of Ohio’s most vulnerable residents over 65. And their resulting fears may prevent them from visiting doctors for vital scheduled appointments for other illnesses, surgeries, and chronic conditions, or prevent them from going out to shop for needed food, medicines, and health supplies, or put undue stress on those least able to endure it.

Issuing dramatic warnings can be as much about life-and-death decisions as not issuing them. Not going to work for those under 65 can pose as much a collective societal risk as going, and panic may be as deadly for a country of 330 million as infection is for those not in high-risk groups—and all such suppositions can change by the time this essay is read.

Humility, not certainty—much less accusation and panic—should be the order of the day.