Congress Can’t Handle the Truth About the Coronavirus Recession

As the economics blogger Nathan Tankus notes, the economy was only able to rise from its sickbed last month because of the federal government’s fiscal life support. The disbursement of $1,200 relief checks and $600-a-week federal unemployment benefits has enabled personal income in the U.S. to rise since the onset of the pandemic. But once the stimulus checks were cashed, household income began to decline; and if Congress refuses to extend the $600 unemployment bonus when it expires at July’s end, consumer purchasing power will plummet.

Recovery is a process. Photo: Kerem Yucel/AFP via Getty Images

America’s economic crisis is worse than it looks. For that reason, it’s about to get worse than it is.

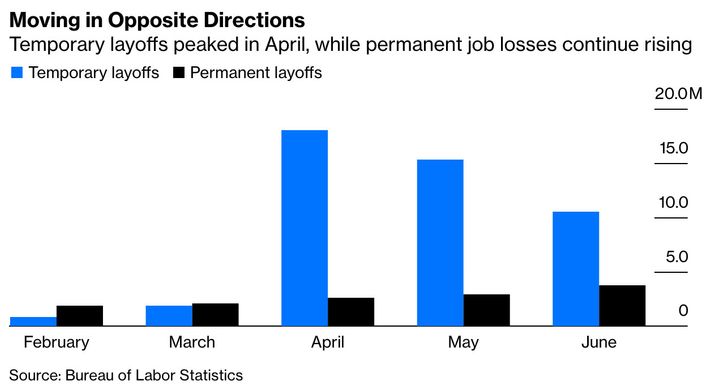

Last week, the Labor Department released a report showing that permanent jobs losses — which is to say, the number of U.S. workers who were fired (not furloughed) — was 588,000 higher in June than it had been in May. America’s overall unemployment rate remained above 11 percent, higher than it had ever been between World War II and the onset of the pandemic. And these figures were based on surveys taken in mid-June, before the Sun Belt reopenings crashed into new coronavirus outbreaks and kicked into reverse.

Nevertheless, the combination of economic reopening, UI benefits propping up consumer demand, and a government program designed to keep workers technically on the payrolls of inoperative (and potentially, soon-to-be nonviable) businesses allowed the economy to gain 2.5 million jobs in June. Economists had expected a net contraction in payrolls. These two facts were enough for the business press to pen celebratory headlines like “Record jobs gain of 4.8 million in June smashes expectations.” And that was enough to curb the congressional GOP’s appetite for further relief. As PBS NewsHour reported:

Republicans say the numbers vindicate their decision to take a pause and assess the almost $3 trillion in assistance they already have approved … “They are less than urgent, less than inclined for another package,” said Rep. Patrick McHenry, R-N.C., a GOP leader when his party was in the majority. “There is less urgency to go strike a hard deal — and this one would be a hard deal. Doesn’t mean it won’t happen, I just think the urgency is far lessened.”

This is about as rational as a scuba diver deciding that the fact that he is still able to breathe — despite being deep underwater — proves that he’ll never need to refill his oxygen tank.

As the economics blogger Nathan Tankus notes, the economy was only able to rise from its sickbed last month because of the federal government’s fiscal life support. The disbursement of $1,200 relief checks and $600-a-week federal unemployment benefits has enabled personal income in the U.S. to rise since the onset of the pandemic. But once the stimulus checks were cashed, household income began to decline; and if Congress refuses to extend the $600 unemployment bonus when it expires at July’s end, consumer purchasing power will plummet.

What’s more, although the CARES Act’s provisions have left many working people better off, others have fallen through our welfare state’s many cracks. Last month, nearly 14 million U.S. children lived in food-insecure households, according to a new report from Brookings; at the peak of the Great Recession, that figure was 5.1 million. Roughly one-third of U.S. households have not made their full housing payments for July, according to a survey by the online retail platform Apartment List. In New York City, one-quarter of all renters haven’t paid their landlords since March. State law forbids landlords from evicting cash-strapped tenants while social-distancing orders remain in effect. But no rent has been forgiven — New Yorkers who were housing burdened even before this crisis are simply accruing thousands of dollars in debt. If such arrears are not promptly repaid — which they won’t be — then many landlords will be unable to make their mortgage payments. This crisis is especially acute in NYC (the rental capital of America), but such webs of unpayable financial obligations hang over every U.S. city. The human costs of this unresolvable math are partially limited by a federal moratorium on evictions that covers about one-fourth of all U.S. renters. But, absent congressional action, that moratorium will expire by the fall.

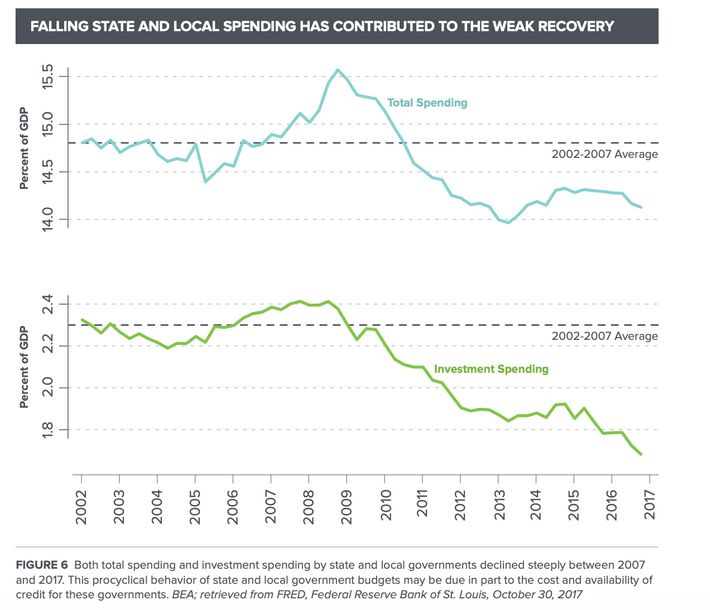

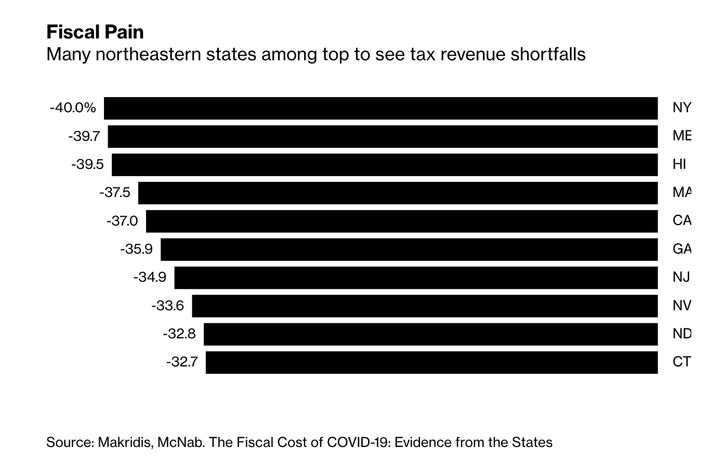

Meanwhile, states and municipalities are hemorrhaging public jobs and slashing social services. This component of the crisis is wholly solvable: The U.S. federal government boasts the exorbitant privilege of being able to print the world’s reserve currency. It could use that exceptional fiscal capacity to plug the holes in every state’s budget, thereby ensuring that sub-federal governments don’t actively deepen the recession by slashing spending, employment, and investment. But Senate Republicans have refused to do so. As a result, gargantuan revenue shortfalls are poised to sabotage any theoretical post-coronavirus recovery, just as they did post-2008.

Even if the U.S. government had forgiven all rent and mortgage payments, bailed out state budgets, kept food insecurity at its normal (scandalous) level — and suppressed the pandemic as effectively as the median European nation — we were still likely to be in for prolonged economic hardship. The present recession emerged from a public-health shock, not a structural imbalance in the financial system or real economy. And this led many bullish analysts to predict a rapid return to baseline once COVID-19 had passed: Since the economy’s fundamentals were sound, recovery wouldn’t be stymied by the need to unwind massive misallocations of capital like those produced by the housing bubble. But this assessment overestimated the government’s capacity to keep still-viable small businesses afloat for the duration of the outbreak — and ignored the possibility that the experience of living through a world-historic pandemic would foster permanent changes in consumer spending patterns. A world where remote working is permanently an order of magnitude more prevalent than it was pre-pandemic is one in which a wide variety of service businesses are no longer viable. Reallocating capital away from restaurants reliant on the high-volume patronage of office workers, or movie theaters, or airlines toward enterprises better suited to post-2020 consumer appetites will be a long and painful process. But this reality — that there is no way to breezily return to the economy as we knew it in January — was also always likely to be obscured by this summer’s economic data. If you put America’s largest cities into total lockdown, you’re going to see a falling unemployment rate and eye-popping job gains when you start to reopen them, as temporarily unemployed workers are called back en masse. And this will look like the start of a rapid recovery (so long as you make sure not to look at those permanent job losses).

Graphic: Bureau of Labor Statistics

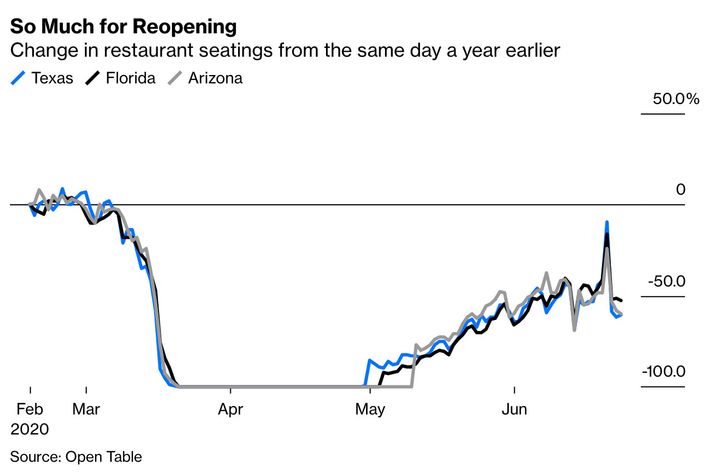

Of course, Congress did not mount a flawless fiscal response to the crash. And more importantly, the U.S. government failed spectacularly in containing the virus.

Averting a prolonged period of mass unemployment, homelessness, and poverty would have required renewing and expanding the fiscal supports that Congress passed in March, even if America’s pandemic had followed the same trajectory as Europe’s. The measures necessary for restoring economic normality after another several months of widespread lockdowns are more radical than our political class is prepared to imagine.

Graphic: Open Table

At present, congressional Republicans are committed to cutting the CARES Act’s federal unemployment benefits, while keeping the total fiscal cost of the next coronavirus relief package under $1 trillion. For perspective, back in May, 100 U.S. business leaders advised Congress to spend that much on fiscal aid to states alone.

The Democratic Party’s view of the crisis is much less obstructed by ideological commitments than the GOP’s. But obstructed it remains. When passing its blueprint for the next relief package in May, House Democrats withheld aid measures that had broad support within their caucus and among the party’s top economists — solely because including them might have raised the bill’s estimated cost from $3 trillion to $5 trillion, and they felt that they could not “sell” a $5 trillion package to the public.

Headline unemployment data won’t camouflage the depths of this crisis forever. Reopening-induced job gains will eventually show diminishing returns; if current epidemiological trends persist, they may wither quite soon. But by the time the scale of our social disaster is clear enough to be seen from Capitol Hill, the measures necessary for relieving it will have to be nothing short of visionary.

No comments:

Post a Comment