Navalny vs. Putin: The Next Round

Alexei Navalny has been getting under Putin’s skin for a long time, and recently things came to a head. In January 2021, the Navalny Channel on YouTube featured the protest film, Dvorets dlya Putina: Istoriya Samoy Bol’shoy Bzyatki (Putin’s Palace: History of the World’s Biggest Bribe), an immensely popular exposé since viewed 113,654,953 times.

To counter the notable lack of reporting by the Russian press on Navalny’s mistreatment at the hands of the Putin regime, the film begins with this précis: “In August 2020, on the order of Vladimir Putin, Navalny was poisoned with Novichok chemical warfare agent. He survived, came back to Russia, and was arrested right at the airport. On January 18, 2021, the court unlawfully arrested Alexey Navalny and sent him to Matrosskaya Tishina Prison.” An invitation to protest followed: “For many years, Navalny has been fighting for our rights. Now, it’s time for us to fight for him. On January 23, at 14:00, take to the main streets of your cities. Don’t stand on the sidelines.” Marches to protest Navalny’s wrongful poisoning, arrest, and imprisonment would indeed be held by his supporters on Saturday January 23, all over Russia. One pollster estimated the crowd in Moscow alone to number 35,000.

Next, Navalny himself appears saying, “Hi, Navalny here. We came up with this investigation when I was in intensive care, but we immediately agreed that we would release it when I returned home, to Russia, to Moscow, because we do not want the main character of this film to think that we are afraid of him so that I would tell about his worst secret while I was abroad. One of the most devoted admirers of our work, the same one on whose orders I was poisoned, is Vladimir Putin. He is definitely watching this now, and his heart is filling with nostalgia.” Navalny proceeds to take a trip through Putin’s past, beginning at the building on Radeberger Strasse in Dresden where the early corruption schemes of then-KGB agent Vladimir Putin and his cronies were conceived, “by those who would later arrange the biggest robbery in the history of Russia -- simply, to steal all the national wealth.” Navalny illustrates this point using material from Putin’s actual case file from Germany’s Stasi archives.

The rest of the film consists of a flyover of Putin’s pleasure palace in Krasnodar Krai, accomplished by launching a drone from a boat offshore to film the “legendary footage” of the edifice, a massive, 190,424 square foot castle on a promontory in Gelendzhik, near Sochi overlooking the Black Sea. Navalny also homes in on numerous tarps and plywood and other humiliating proof that the building was badly constructed, leading to mold, leaky ceilings, and other problems. “They literally threw billions into the trash and have now started over.”

For all of the above reasons, Putin has been livid and intent on some sort of retaliation. In early February, videos in support of Putin suddenly began appearing on social networks. The footage was shot in numerous regions as instructed by the presidential administration and as organized by Putin’s political party United Russia.

The sites for these videos were carefully chosen. One location was Barnaul, a city in Siberia where their pro-Navalny protest on January 23 is said to have been the city’s largest political rally in 15 years. The Instagram video supposedly showed an “All-Russian Flash Mob in Support of Putin!” The “flash mob” in question consisted of young workers of the Barnaul ATI chemical plant in  matching bright blue overalls and face masks, standing at attention and waving Russian flags. Another supposed “rally for Putin,” this time of state employees and schoolchildren, was assembled to shoot a video in Volgograd. Both groups had been told they were to be part of a music video for the Russian rock group Lyube (IPA). They were not demonstrating for Putin, who was not even mentioned.

matching bright blue overalls and face masks, standing at attention and waving Russian flags. Another supposed “rally for Putin,” this time of state employees and schoolchildren, was assembled to shoot a video in Volgograd. Both groups had been told they were to be part of a music video for the Russian rock group Lyube (IPA). They were not demonstrating for Putin, who was not even mentioned.

The students of Kutafin Moscow State Law University (MSLA) were invited to participate in a flash mob in support of Russia “as a leader in the fight against COVID” on February 5, promised that the video would be shown on the internet and on TV, and that each participant would be awarded a letter of thanks before the State Duma legislature. According to the students who participated, shooting took place in a Moscow hotel. They were asked to wave flags while reading the following text from a teleprompter: “We have one president. We will defeat the virus with him. We have one president. Together, we will win. Vladimir Vladimirovich, we are with you! Putin is our president!” The Dozhd television channel published a photograph of the teleprompt slide. An MSLA graduate revealed that some students refused to participate but would not speak with the reporter directly for fear of sanctions from the university. They claim that the school administration was unaware that students were “deceived by the organizers from the State Duma.”

A third film clip was taken at Belgorod’s Institute of Arts and Culture (BGIIK). The BGIIK students were asked merely to “dance with Russian flags to record a patriotic video.” Later they were shocked to see their dance on Instagram with the hashtag #PutinNashPresident (#PutinOurPresident). According to the students, a song praising Putin followed by youthful voices, shouting “Putin is our president!” and “Vladimir Vladimirovich, we are with you!” were dubbed in. According to the students, they said no such things. The incident led to a scandal. Their parents complained that their children had not been warned that the video was being staged to show support for the president, and that they had not shouted the words in the video. On February 8, the local newspaper Belgorod No. 1 published a transcript of a conversation in which the BGIIK Vice-Rector Natalya Baranichenko and Rector Sergei Kurgan apologized to the students. Baranichenko, who had organized the filming, was made to resign. She has not worked at BGIIK since February 10 and the leadership page on the BGIIK website no longer mentions the former vice-rector.

This pathetic ruse on the part of Putin, his administration, and United Russia serves only to demonstrate the popularity gap between Navalny and Putin -- one, inspiring tens of thousands of ordinary Russians to risk arrest and take to the streets, and the other, reduced to fabricating bogus “rallies” of supposed “supporters” in lieu of same.

Lynn Corum is a translator of Russian who studies developments in the Russian press that affect America’s national interests. She has been researching and writing on Putin’s stated plans since 2009, and is a world expert on Project Russia, the Kremlin’s published state ideology.

Poll: More Russians Reject Putin than in Nearly a Decade

A poll by the Levada Center in Russia found on Friday that more Russian citizens hope to see an end to the regime of President Vladimir Putin today than in years, at least since a 2013 poll immediately before the annexation of Crimea, Ukraine.

The Moscow Times noted the occupation of Crimea appeared to buoy Putin’s support somewhat, elevating “patriotic fervor,” but that much of that support has dwindled as Russia’s economy continues to flounder and Putin has increased repression against political dissidents.

The ongoing dispute over the arrest of opposition leader Alexei Navalny, imprisoned immediately upon his return to Russia after recovering from an attempted poisoning in Germany, has led to widespread protests across the country. Putin denies Navalny’s claims that he was behind the poisoning, telling reporters that, had he wanted Navalny dead, he would have killed him.

The poll published Friday found that 41 percent of respondents would prefer Putin not stay in power past 2024. Nearly half, 48 percent, said they supported a prolonged tenure for Putin. Men were less likely to support Putin than women and a higher percentage of young people also expressed a desire for change. Among women, 35 percent said they would want to see a change in their presidency in 2024.

“It is the highest objection to Putin’s re-election since October 2013, when the share of those opposed to the prospect of his fourth term stood at 45% against 33% who were in favor,” the Moscow Times noted.

Russia has experienced nationwide protests resulting in at least dozens of public arrests surrounding the case of Alexei Navalny, a longtime public opponent of Putin’s who has urged a change of the guard at the Kremlin. The protests intensified in January following Navalny’s arrest. On Friday, Russian authorities confirmed Navalny had been transferred out of his prison to a penal colony to complete a two-year sentence for alleged parole violations.

Last year, Navalny’s team rapidly flew him out of the country to Germany after he fell ill. German doctors announced they had found traces of Novichok, a Russian chemical weapon historically used by the government, in his system. Navalny personally accused Putin of attempting to have him assassinated when he awoke from his coma following the poisoning.

Navalny chose to return to Russia upon recovery, resulting in his immediate arrest. Despite conceding the arrest was politically motivated, the international human rights organization Amnesty International stripped Navalny of his status as a “prisoner of conscience” this week after an “orchestrated campaign” to smear his reputation, admitted spokesman Alexander Artemev.”

Independent of the Navalny case, Russians have increasingly expressed displeasure with Putin’s handling of the Chinese coronavirus pandemic, which has impacted the nation severely. Russia has documented nearly 4.2 million Chinese coronavirus cases since the pandemic began and 83,900 deaths, more than all but four other nations. The tally only takes into account official government statistics, which suggests Russia’s true toll is much higher, but likely overshadowed by the true numbers from countries like China and Iran, whose numbers experts have doubted.

Russian officials admitted in December they had significantly undercounted the number of cases and deaths in the country for months. The death toll, in particular, Moscow revealed was at least three times higher than the prior official statistics showed. The numbers also show a significantly higher death rate than many other countries, including some with higher case counts.

Doctors throughout the country have repeatedly complained that the government has not provided them sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE) or other tools to handle highly contagious cases. The complaints have corresponded to an increase in mysterious deaths of health workers in the country, a significant number of which died after, according to police, they “fell” out of the windows of tall buildings. Some reports indicated that the falls preceded arguments with Russian officials about the lack of aid.

Putin has increasingly attempted to elevate his support by warning the nation of the need of unity in the face of alleged foreign threats. This week, Putin announced that his government had evidence of unspecified Western campaigns to “destabilize” the country, ordering top counterintelligence agencies to focus on foreign governments trying to “derail our development, slow it down, create problems alongside our borders, provoke internal instability and undermine the values that unite the Russian society.”

Follow Frances Martel on Facebook and Twitter.

Alexei Navalny leads Russians in a historic battle against arbitrary rule, with words echoing Catherine the Great

Tens of thousands of young Russians are protesting the leadership of Vladimir Putin nationwide in freezing temperatures. Thousands have been arrested.

Central to these well-organized protests is Russia’s opposition leader, Alexei Navalny. His courageous actions and words have inspired demonstrators to believe that they can change Russia.

As a scholar of Catherine the Great and the literature of Russia’s noble writers who served the empire, I pay attention to language.

Navalny uses some historically powerful words that speak to all Russians about the illegitimacy of their leaders and government.

Do experts have something to add to public debate?

A normal country

A lawyer, Navalny became a prominent regime critic a decade ago, when he created the Anti-Corruption Foundation and ran for mayor of Moscow. Funded by Russian donors, his national foundation collects stories of government corruption and produces YouTube videos that document, with drone footage, the secret luxury properties of government officials.

Navalny is not a Moscow flash in the pan. Members of his team have built a presence in about 50 cities using their political party, Russia of the Future. He has suffered multiple arrests, convictions and physical attacks.

Navalny’s “smart” voting platform recommended that candidates unite opposition votes last year against Putin’s United Russia party, which lost seats in Moscow, Khabarovsk, Tomsk and Novosibirsk. Putin’s party faces further losses and delegitimization in parliamentary elections in September.

Last summer, Navalny was poisoned in an apparent assassination attempt, and the Russian government allowed him to be evacuated to a German hospital, where he recovered. One of his YouTube videos featured what he said was a member of the Kremlin’s security agency, the FSB, confessing that the agency poisoned Navalny. Supporters live-streamed his return to Moscow and arrest on Jan. 17.

Sentenced to nearly three years in prison on Jan. 22, Navalny made a courtroom speech that mocked the “performance” of justice.

“This is what happens when lawlessness and arbitrary power become the essence of a political system, and it is horrifying,” he said. “But it is even worse when lawlessness and arbitrary power pose as state prosecutors and dress up in judges’ robes. It is the duty of every person not to submit to you or such laws.”

Interrupted by the judge, Navalny repeated these sentences.

In that statement, Navalny used the term “proizvol,” a word that means arbitrary power, and is often translated as tyranny. Russians have used this word for centuries to describe the abuse of power at all levels of government and society. Like Soviet dissidents before him, Navalny is demanding that the government uphold its own laws.

Navalny concluded with a call for “normal justice, normal relations, participation in elections, participation in the distribution of national wealth.”

Navalny echoes Russians’ historical wish: to live in a normal European country governed by the rule of law. Empress Catherine the Great – a German – first expressed this enlightened goal in her “Instruction” to her Legislative Commission as it began to review Russia’s laws in 1767: “Russia is a European nation.”

Civil society

Navalny’s ideas, his YouTube channel, his foundation and his political party embody one of the most powerful political concepts to arise in the past few decades.

Since the 1990s, philosophers such as Michael Walzer have revived the notion of “civil society” to empower citizen democracy in Eastern Europe and Russia. In this approach to society, nongovernmental organizations such as churches, clubs, unions, neighborhoods, foundations and political parties bring people together. They create civic networks that can check the power of government and promote the greater good.

These nonprofit organizations and advocacy groups in Russia were initially funded in the 1990s by the United States, the European Union and the philanthropist George Soros. Putin branded these organizations as foreign agents after massive demonstrations against his reelection in 2012 amid reports of election fraud by independent Russian election monitors.

Western notions of civil society resonated in Russia because civic duty has been essential to Russian culture for centuries.

In 1767, during the Scottish Enlightenment, Adam Ferguson published “An Essay on the History of Civil Society” to promote an idea going back to the Greeks. Ferguson wrote that in a civil society, the social, political and military elites had a civic duty to the greater common good. His great fear was that elites were too corrupted by privilege to do their duty.

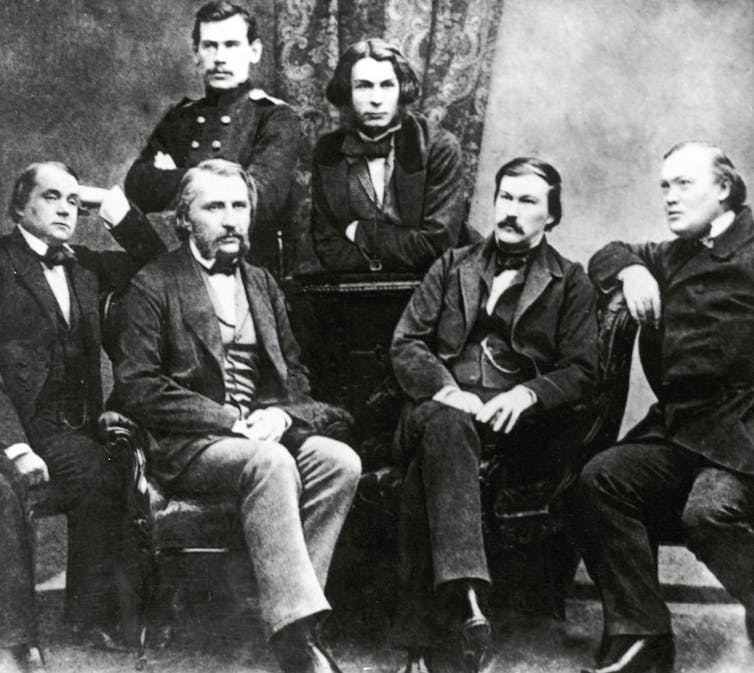

Nineteenth-century philosophers such as Hegel recast Ferguson’s work and transmitted their ideas to the Russian intelligentsia. The notion of a duty to the public good was the lifeblood of the Russian nobility, who were compelled to serve in the military or civil service and ran the Russian empire.

A post-Putin Russia?

Nobles like the writers Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Turgenev exemplified those civic ideals in their novels - the novels that students in Russia read today to pass their Unified State Exams. Brought up on new and old notions of civil society, young people understand when Navalny says that his movement is not about him, but about them and their future.

The Russian government playbook has been to exile major dissidents abroad and delegitimize them].

But Navalny heroically returned to his country after the government’s assassination attempt, even knowing that he faced certain arrest and prison, and possibly death. His team has used his palpable bravery to mobilize demonstrators in some 150 cities throughout Russia.

The demonstrators were equally motivated by Navalny’s release, two days after his return, of the bombshell two-hour video “A Palace for Putin: The History of the Largest Bribe.” It documents Putin’s decades-old network of elite bagmen, his expensive mistresses and his luxury tastes for US$850 Italian gilded toilet brushes – which became a new protest symbol. An existential challenge to Putin’s legitimacy, the video has over 110 million views.

As Russians prepare for parliamentary elections in September, they sense that historic change may once again be possible – with the potential for a more democratic future.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]

No comments:

Post a Comment