Big Dirty Money: “White-collar crime” and the nature of capitalism

Big Dirty Money, The Shocking Injustice and Unseen Cost of White-collar Crime , by Jennifer Taub, Viking, New York, 2020

The term “white-collar crime,” which appears in the subtitle of a new book, Big Dirty Money, The Shocking Injustice and Unseen Cost of White Collar Crime, was apparently first coined during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The phenomenon is as old as capitalism itself. In Jennifer Taub’s work the focus is on the United States, but the reality she describes, though nowhere more explosive than in the US, is a global one.

Taub, a professor at the University of Western New England School of Law in Springfield, Massachusetts, brings together much valuable data and information on white-collar crime and on the connection between its recent prominence and that of extreme wealth inequality. Her book is noteworthy for correctly focusing on the role of class in shaping the lives and futures of humanity.

The author indicates that white-collar crime must be defined far more broadly than embezzlement or what might be termed low-level forms of corruption. She gives some recent examples of white-collar criminals, all extensively reported by the WSWS: the Sackler family, worth some $14 billion (as of the book’s printing), responsible for the marketing of oxycontin, which led to 232,000 overdose deaths between 1999-2018; Pacific Gas and Electric, to blame for the deadly Camp Fire of 2018 in California, which left 85 dead and the town of Paradise completely destroyed; and General Motors, whose faulty ignition switches led to sudden engine shutdowns and at least 124 deaths between 2002 and 2014, when the cars were finally recalled.

All of the above criminals escaped serious punishment, paying for the lives lost through fines that amounted, even where sizable, to the mere cost of doing business.

Taub makes a number of useful points in the course of discussing these issues. As she notes, the US has a prison population of 2.3 million, but even the very few white-collar criminal convictions (as opposed to civil cases) rarely lead to jail time. The few who have been jailed— Michael Milken is one prominent example—have served their time in “country club” prisons, facilities whose very existence illustrates the fact that incarceration is a weapon principally designed for and used against the working class.

Taub is hardly the first to note the huge gulf between the treatment of the poor and the wealthy by the so-called justice system. Petty offenses get harsh punishment while big criminals get off scot free. Eric Garner lost his life for selling untaxed loose cigarettes, Taub points out, while the executives of companies responsible for death and misery on a vast scale have paid no price. Indeed, as Taub was putting the finishing touches on this volume last May, this class reality was brought home, to the horror of vast numbers of people all over the world, in the murder of George Floyd after he was accused of passing a small counterfeit bill at a neighborhood convenience store.

The magnitude of the class gulf today is one that could barely have been imagined by famed French novelist Anatole France when he famously ironized, “The law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal bread.”

The last 40 years have seen an uninterrupted growth of white-collar crime and of all the abuses associated with it. Government has done much to facilitate this growth, and the political representatives of the corporate elite have often shared in the spoils. Furthermore, this has been a thoroughly bipartisan operation. As Taub explains, “in the Carter and Clinton administrations, legislation was enacted that allowed the credit default swap and private mortgage securities markets to flourish, enabling the toxic mortgage-backed securities that eventually blew up the banking system in 2008.”

This history serves to illustrate, as Taub does not point out, that the dividing line between the legal and the criminal, to put it mildly, is a porous one in the capitalist economy.

After the 2008 crash, the greatest since the Great Depression, the get out of jail card really came into its own during the two terms of Democratic President Barack Obama. “The Justice Department led by Attorney General Eric Holder from 2009 to 2015 let every bank executive engaged in accounting or securities fraud get away without prosecution,” writes Taub. Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr., another Democrat, brought no charges, except against a tiny bank that no one had ever heard of.

Taub’s polemical zeal in exposing glaring injustice can only be welcomed. Her outlook, however, could perhaps be summed up in a paraphrase of the Biblical reference to the poor—we will always have white-collar criminals with us. Or to put it somewhat differently, capitalism is here to stay.

She reviews the history, over most of the last century, of what she terms “corporate crime waves and crackdowns.” This is a cyclical conception, in which capitalist “excesses” are followed by regulation and reform, until the pendulum swings back toward corruption once again. The Gilded Age was followed by the Progressive Era, whose birth is associated with the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. Later, after the speculative boom of the 1920s, came the reforms associated with Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Big business steadily attempted to evade or circumvent regulation, and the decades from the 1940s through the 1960s are dubbed a period of “invisible industrial violations,” as Taub puts it, leading to scandals such as Love Canal and the thalidomide birth defects. This was followed by yet another decade of regulation, this time under the improbable reformer Richard Nixon. The Environmental Protection Agency was established, along with the Consumer Product Safety Commission. After Watergate, other legislation established the Federal Election Commission.

American capitalism unquestionably did undertake major regulatory efforts in the last century. What Taub does not discuss, however, is the connection between the last 40 years, a period of uninterrupted deregulation and social counterrevolution, and the crisis and decline of US capitalism. There is little or no mention of globalization in this book, and no discussion of the financialization of the economy. We are left with the supposed problem of human nature, and of what is seen as an endless struggle against greed. Behind white-collar crime, however, is not simply greed, but a system of production and distribution that produces and requires it.

A cyclical theory of inequality and corruption followed by regulation and reform does not explain the last several decades. The Biden administration and its backers, who it is safe to presume include Professor Taub—even if she recognizes, quoting New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd, that Donald Trump “did not come to Washington to clean up the tainted system; he came to bathe in it”—claim that a new era of reform is beginning. The conditions confronting US and world capitalism, however, are entirely different from those of the post-World War Two era.

The capitalist media dwell incessantly on misleading catchphrases like “systemic racism,” but the conditions described by the author demonstrate that what is truly systemic to capitalism is class inequality and all of its consequences. The solution to the misery that Taub details—the lives lost to poverty, illness and police violence—must also be systemic. It is not the pipe dream of a new era of reform, but rather the overthrow of the capitalist system and the building of a socialist society.

This is not Taub’s program. The final chapter of her book is entitled, “The Six Fixes,” and what she proposes is not much more serious than this somewhat glib heading. She calls for a new Department of Justice division devoted to white-collar crime; the amendment of the bribery laws to make it easier to convict politicians like Virginia’s former governor Robert McDonnell, who beat a bribery rap because of a legal loophole; legislation to protect journalists and whistleblowers; the restoration of Internal Revenue Service funding, after years and years of cuts that have been designed to cripple any effort to go after massive tax fraud; a nationwide registry for white-collar convictions; and improved data collection on white-collar crime.

To call these reforms would be a genuine stretch of the definition. Some of them amount to little more than improved methods of keeping track of the crime taking place, not doing anything about the conditions themselves. Even New York Times columnist James B. Stewart, in his review of Big Dirty Money, observes about these “fixes,” “These are earnest and well-intentioned, but small bore given the scope of the problem [Taub] so vividly illustrates.” It should also be pointed out that the fact that Taub, discussing whistleblowers, mentions Daniel Ellsberg and Karen Silkwood, but not Julian Assange, Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden, reflects her allegiance to what passes for bourgeois liberalism today.

Despite its serious faults, and although Big Dirty Money does not go much beyond a description of important aspects of 21st century capitalism, the exposures in this volume are vivid and at times gripping, and the book is therefore recommended, with the above caveats.

Protect the Family at All Costs

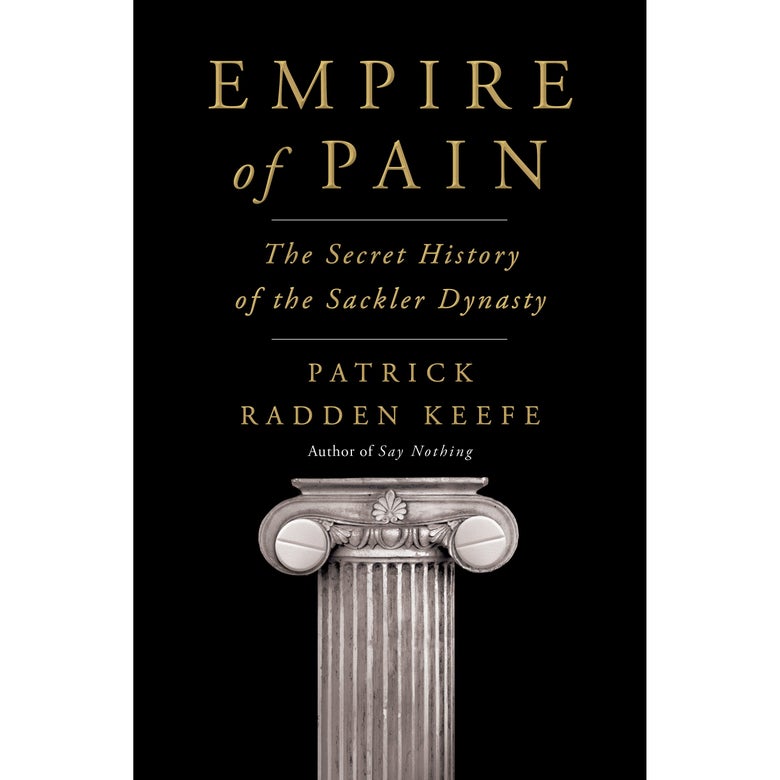

A damning portrait of the Sacklers, the billionaire clan behind the OxyContin epidemic.

Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

In the late 2000s, an employee of Purdue Pharma was stunned by the words of the corporation’s in-house counsel. At a meeting, the company’s lawyer, Stuart Baker, had been praising three former members of the leadership team, including his own predecessor. Those three men had pleaded guilty in 2007 to making fraudulent claims about the harmlessness of Purdue’s cash cow product, OxyContin, and had been forced to resign. “Those people had to take the fall to protect the family,” Baker said, as quoted in Empire of Pain, Patrick Radden Keefe’s masterfully damning new book about that family, the billionaire Sacklers, who owned Purdue. The company’s foremost priority, Baker went on to remind all present, was “to protect the family at all costs.” The unnamed (and now former) Purdue employee who witnessed this little speech told Keefe, “I remember going home and saying, ‘Where the fuck am I working?’ ”

Empire of Pain, Keefe explains in his afterword, is a dynastic saga. Like Purdue, it is all about the Sackler family: how it transformed American medicine, the key role it played in the opioid crisis that now costs tens of thousands of Americans their lives every year, and the family’s belated and incomplete downfall. The Sacklers went from an esteemed clan known primarily for their philanthropy on behalf of cultural, educational, and scientific institutions—including, most famously, the spectacular Sackler wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which houses the Temple of Dendur—to public disgrace and repudiation. Among the final scenes in Empire of Pain is a student activist happily watching the Sackler name being chipped off the facade of a building at Tufts University. The family threatened to sue, claiming that the university was violating an agreement it had made when it received donations from one of its members. Keefe calls this “a graphic measure of the Sacklers’ vanity, and of their pathological denial, that the family was prepared to debase itself by trying to force its name back onto a university where the student body had said, quite explicitly, that they found it morally repugnant.” It’s also an illustration of how much the very rich, when crossed, operate like the Mafia, though they reinforce their power with shell companies and lawyers rather than omertà and violence.

Keefe is no stranger to covering gangster tactics. His previous book, 2019’s Say Nothing, was an acclaimed bestseller about the abduction and murder of a widowed mother of 10 by the Irish Republican Army, and for the New York Times Magazine, he wrote about the financial management of the Sinaloa drug cartel in Mexico. In fact, it was Keefe’s interest in how the cartels function as businesses that piqued his curiosity about Big Pharma, and specifically the Sackler family, which he wrote about for the New Yorker in the article that became the basis for Empire of Pain. Keefe doesn’t lean too hard on the Mafia comparison in this book, but when he refers to Howard Udell—Purdue’s ultraloyal longtime staff attorney, and one of the three men who took the fall in 2007—as the Sacklers’ “consigliere,” the dart hits home.

The Sackler story begins with three striving brothers, Arthur, Mortimer, and Raymond, born to a Jewish immigrant grocer and his wife in early 20th century Brooklyn. All three became doctors. Arthur, the eldest and a superhuman dynamo, seemed to start a new enterprise every week; after his death from a stroke in 1987, one of the greatest challenges facing his heirs was the task of locating all of his assets and paying off unexpected debts. Arthur Sackler didn’t like people knowing his business—literally—so no one had a grasp of the entire financial picture of his estate. This was partly because some of his dealings were ethically dubious. He secretly owned a controlling share in the chief competitor of one of his own firms, for example, and he kept his name out of medical newsletters that he published to conceal a self-interested editorial bias in favor of pharmaceuticals. When Arthur became obsessed with both collecting art and donating to cultural institutions in exchange for having galleries and wings named after himself and his family, he faced a challenge, as Keefe writes, to “reconcile this ardent desire for recognition of the Sackler name with his equally strong preference for personal anonymity.” He balanced this skillfully. In the art and philanthropy world, Arthur was known to have lots of money, but no one seemed to know where he’d gotten it.

The answer was Valium, the first $100 million drug in history. Arthur didn’t own F. Hoffmann-La Roche, the company that manufactured the tranquilizer (although he swanned around the headquarters so often that there were rumors he ran it). Though Arthur was an early proponent of psychopharmaceuticals, his greatest expertise lay in advertising and marketing, services provided by his agency, McAdams. The first inductee into the Medical Advertising Hall of Fame, Arthur Sackler was credited by that august institution with pioneering the field and bringing “the full power of advertising and promotion to pharmaceutical marketing.” Some of his innovations included making unfounded claims for the nonaddictive nature of Valium, producing the first promotional insert designed to look like editorial content (in the New York Times, no less), and creating ads filled with the testimonials of practicing MDs who, upon investigation, turned out to be entirely fictional.

Arthur died before OxyContin was developed, and his widow and children, according to Keefe, energetically strive to distance themselves from that most notorious of Sackler-associated products. Purdue, which the brothers bought in 1952, was run by Mortimer and Raymond’s children and grandchildren. But Empire of Pain amply demonstrates that Arthur created the playbook used to make OxyContin a blockbuster drug, from incentives for sales reps to speakers, publications, and “grassroots” advocacy groups that are secretly funded by the manufacturer. Opioids are powerful and addictive painkillers, but not necessarily dangerous if used carefully and properly. Purdue Pharma, however, did nothing to ensure that OxyContin was used that way, and in fact encouraged its misuse. Internal documents and correspondence quoted in Empire of Pain prove that Purdue’s staff and leadership, including several of Arthur’s nephews and nieces, knew full well that many doctors were operating illegal pill mills. Yet the company refrained from reporting them because it made money from every bogus prescription.

If you are someone who engages in this kind of sneaky conduct, the last person you want reporting on you is Keefe. Although the material in Empire of Pain is more complex and less action-packed than the crimes and terrorism of Say Nothing, the narrative is just as involving. Keefe has a knack for crafting lucid, readable descriptions of the sort of arcane business arrangements the Sacklers favored. He is also indefatigable. He will interview the yoga teacher you brought to Turks a few times to help with your bad back and who knows your wife ordered two butlers to escort you everywhere as “human crutches.” He will find the doorman who was standing outside your aunt’s apartment building when your cousin jumped out the window to his death. And he will not only dig up the third grade classmate who remembers you as “innocent and mocked and friendless and rich,” he’ll quote that classmate adding that “to be ostracized on that basis” at such a tony private school, “you had to be pretty fucking rich.”

The Sackler infighting described in Empire of Pain will surely prompt many comparisons to the HBO series Succession, but a real-world parallel also comes into focus. Around this time last year, I was knee-deep in memoirs by Trump staffers and associates, and while the Sacklers may be more housebroken than the former president, there are some significant similarities. The Sacklers who ran Purdue surrounded themselves with yes men and interfered with the more prudent employees who sought to curb their excessive demands for more and more OxyContin sales. They considered only their own enrichment when making any business decision. They lack basic empathy for other people, or any understanding of the difficulties life presents to those less fortunate than themselves. Richard Sackler—Arthur’s nephew and the driving force behind the OxyContin campaign—adamantly insisted that neither Purdue nor OxyContin was to blame for the abuse of the drug, and pointed his finger at the addicts themselves. They consider themselves victimized whenever they don’t get what they want or anyone criticizes them. The Sacklers are prone to feuds and tantrums and, finally, as Keefe puts it, there is their “reluctance to concede, even hypothetically, the possibility of error or wrongdoing.”

Held up to the Sacklers, Trump seems less outrageous and sui generis, his awful behavior less a manifestation of his dysfunctional individual upbringing than typical of his kind—the mediocre children of the rich. Only worse, of course—or is he? Cosmetically, Trump is certainly the more appalling, but when it comes to the deaths that can be chalked up to his heedless selfishness … well, Keefe’s book makes clear, the Sacklers can give him a run for his money.

No comments:

Post a Comment