One of the Greatest Rags to Riches Story Told

FICTION:

THE AIR BETWEEN OUR TUBS: Borrowed Dreams

Available on eBook for $5.

https://www.amazon.com/AIR-BETWEEN-OUR-TUBS-Borrowed-ebook/dp/B09F1DKHQW/ref=sr_1_

THE AIR BETWEEN OUR TUBS: Borrowed Dreams

The novel is narrated by the protagonist herself, in a style infused with all the wit and wisdom she needs to draw on to survive the trials she encounters. The music of the prose captures the verve and passion of the lives it traces, and the arc of the narrative follows an epic trajectory, encompassing a vision as broad and embracing as the love that animates her awareness.

Winner of the Hackney Literary Awards

The Air Between Our Tubs explores the depths of human depravity, and the resilience that enables us to triumph over it. In situations of the most dire violence and inhumanity shines a gleam of love, endurance, and commitment to a belief in the possibility of goodness. The novel is a testament to the capacity of these values and beliefs to persist and overcome in the face of the evil they encounter. Despite the heart-wrenching realities it explores, The Air Between Our Tubs is a book of profound hope and ultimately a love story. LEWARO ROAD

Silent Cries, Broken Whispers

CHAPTER 6

The morning of that last summer at Grandview was unlike any before. A stillness hovered over our shack that jarred my young thoughts from the moment my eyes opened. What was wrong? Why hadn’t Daddy gotten up to head to the fields? Momma went about getting a pot of grits on like she was sleepwalking.

“Alex, you and Sarah go down by the river and pick your daddy some them wild grapes. That ’a make ’im feel better. Go on now.”

“What’s wrong with ’im, Momma?” Brother didn’t seem to expect an answer.

Silently she shuffled about, shaking her head at nothing, till she finally pointed us to the door. That was always her signal she wanted us out of the way. There’d be no grits that morning.

I always loved to meander down to the riverbank with my brother where there’d be a thicket of wild muscadine grapes or berries waiting. I squatted for the low vines as Brother reached for the higher. I loved listening to his tales of when the river would one day carry him off on some adventure. At the water’s edge I chattered on ’bout this or that. Alex barely grunted at my notions. Even so, we put a bit more grapes into the basket than our mouths. I remember asking how many basketfuls we could eat in a day. He said nothing and that silence spread like a ground hugging fog. You see, Alex had stopped picking and was gazing up the slope to where Samuel stood staring back. Why’d he come down to the river? He and Daddy only went fishing with Alex on Sunday and they never let me come.

“Alex, you and lil’ Sarah come on back,” Sam said. “Your ma be needin’ you. Come on now.”

Alex didn’t move. It was as if he couldn’t. Still, his eyes followed Samuel. Sam’s boots snapped the vines that lay over the path as he headed back up.

“Why’d Samuel come? Daddy up there waitin’?”

Most times Alex would rather jab me with a pointy stick than hold my hand. Yet he said nothing as he gripped mine.

Up ahead Samuel turned to see if we were following. His expression never broke loose from the haunted look he’d come with. I looked up at my brother, but he only mirrored that fear. You see, nobody had ever come looking for us down by the river. Why would they? It wasn’t near dark and the river wasn’t swollen from the rains. Our eyes darted back and forth looking for the comfort that would not be found. In crashing moments, the reality of that morning would hit me like a belt across my tender face.

The door to our shack was wide open and ’croppers, most I knew, were staring in. What were they looking for? Their heavy silences were deeper than the one I awoke to. Jane, Samuel’s wife, was working near where Momma fiddled with some old bent tins. She stared into their emptiness like she was hunting for something she’d lost. Jane worked at the fireplace and mumbled bits and pieces of her thoughts to Momma. I figured it was woman-talk as I didn’t understand the half of it. Still, I searched their sorrowful glances for something their words hadn’t revealed.

Momma dropped her tin cans yet did not reach for them. She looked down at her feet like she’d simply lost them forever. Lost what, I wondered? Lost forever is a frightening feeling. I felt that fear as Momma’s eyes strayed from mine, looking lost.

Jane finished filling a poultice with smelly bits of roots and herbs, which she dipped in vinegar and squeezed over the fire. Our shack quickly filled with ashy steam. She took the poultice over to my daddy and dabbed it on his forehead and looked to be telling him a secret. He flinched, but still only gazed at the timbers above as if he was searching for something he’d lost. Or was he merely trying to hold on to what he was losing?

I went to show Daddy our basket of wild grapes, but Jane shooed me back with one flip of her wrist.

“Back away, chil’e,” she said.

With her finger pointing at my face she looked hard into my eyes to make sure I minded. At that I knew for sure there was trouble even before Momma gasped and put her hands to her mouth like something was about to fall out. I guessed she didn’t want nobody to hear if the sadness in her eyes drained through her lips that couldn’t close because of all those heavy sobs about to fall out. Again, Momma’s hands cupped her mouth when she heard Jane telling Daddy a secret about Jesus and that it ’a soon be over. I guess Jesus heard her prayer, as on her last word my daddy’s eyes stopped blinking forever.

I knew what had arrived at our door that day had brought the silent cries of one who has nothing and nowhere to hide from the void of it all. Who might save us? Who even would? Still Momma reached out.

“Sarah, go up to the big house. When ya get to the lawn, yell for Mas’er Burney to come.”

Walking about the shack like she was in the wrong place, Mama’s voice faded to whispers like somebody done wrung her throat.

My broken thoughts pounded to whispers in my head. Why’d I need to go up to Jackson’s? What was I gonna tell Burney? I ain’t never said a word to Jackson’s daddy.

Jane wanted me gone, too. “Go on chil’e.”

Momma’s chin trembled when she noticed Alex sitting in the corner with his arms twisted about his head as though hiding his eyes could push it all away. What was it he so feared?

More alone than I could have realized, I sifted my silent cries, wondering why I needed to stop at the lawn up there at the big house? Did Momma forget that I’d long been past the lawn that moated it to play with Jackson? Or did she know I didn’t really count—that to the white folks up there I was just as invisible as the fever that had visited my shack? Only a nobody; one of those who ain’t ’posed to go that far into the shadows of the big house, I recalled Ella saying, unless the white folks are tossing scraps on Christian day. Yet I don’t remember them tossing much of anything our way but misery. Still when I came close to the lawn for some inexplicable reason I stopped. There I yelled over the invisible barrier that now pricked at my fears. My feet felt strangely anchored on the dirt side even as my shadow loomed over the soft green lawn that ended steps from the white veranda; that certain boundary that I’d never seen before now held me back. So, I yelled over it.

“Mas’er Burney come quick! Hurry, come quick!”

I yelled for my daddy so Jesus would come and pull him back from Momma’s sorrow and deliver us from the silence he’d fallen under. I yelled till I thought my throat might come out. It didn’t, but Jackson did. Maybe Jesus could hear me then.

Jackson looked deep into my eyes as he teetered over the banister. I said no more, as the words wouldn’t come. Jackson said nothing back, and ran to his door, yelling even harder than he’d ever yelled at ol’ Isaac. He knew something was wrong, too. You see, there was no distance between Jackson and me.

“Daddy! Come out! Sarah’s here!” Jackson yelled through the open door that was always closed to us.

What could I do to get Burney’s attention? If my voice gave out like Momma’s, would he hear my fears?

Still I knew, knew that only Jackson could get his daddy to come out, ’cause never before had any ’cropper come to the big house yelling for a Burney’s attendance.

“Daddy, I said come out! Your horses got loose again and they’s eatin’ up Momma’s roses. Daddy!”

Jackson knew Burney didn’t like dealing with nothing but his prize horses, and didn’t take to his son’s manipulations, against which he was as defenseless as his momma’s daily brew of tales she’d long dunked him in about her shopping. Nevertheless, he had to keep an eye on his former property, even if it was only driven by his son’s foot stomping for attention.

Burney stepped out reading his newspaper with scant intention of going beyond his fragrant world. Now as I look back, he never really did.

“Daddy, your horses got out again!” Jackson pointed down to the shacks but that didn’t fool Burney none.

“Where’s my horses, Son? I bet they’re in the stables where they belong, ain’t they?”

“No, they’s down visitin’ Sarah. Go see!”

Jackson glanced my way to convey that his strategy was working as usual. But Burney didn’t look to me for confirmation of his son’s tall tale. I doubt if he even knew my name, or to which of his former slaves I was kindred.

“Now, Son, how are they eatin’ your ma’s roses if they’re down in the shacks? That where your ma does her gardenin’? With our niggers? If you interrupted my breakfast for nothin’, I’m tellin’ Ella to whoop your butt good!”

“She already done it. You forgot,” Jackson said.

In their convoluted ways Jackson and his nanny always covered for each other.

“Between you and your ma my memory sure seems to fail somewhere, don’t it?”

Jackson always knew how to direct traffic at Grandview.

“Yeah, down by Sarah’s,” he replied.

Burney headed down the path to the shacks, all the while mumbling something mean about the ’croppers; the very ones whose backs provided him with a life that floated ever so seamlessly on that cool veranda hanging with the scent of jasmine.

Burney walked past me like I didn’t exist. I knew to him I didn’t, ’cause his eyes, like ol’ Issac’s, were that cold shade of near colorless blue. About the color pond water reflects on a winter’s day. He couldn’t see me, so how could his heart feel the anguish of those crumbling moments? Burney yet had to follow me, as he had no idea where Owen and Minerva, born to his property, dwelled.

I glanced back to see if Burney followed, as he looked all so blind to everything but the inconvenience of it all. The corners of his mouth told me so. They’d turned down so hard his young face appeared crimped. Still, he followed me to my door. There the ’croppers swayed an open path for the master—their eyes respectfully downcast as he walked up nodding to nobody. But then he probably couldn’t see us.

All was silent in that dark ashy shack ’cept for Momma’s wailing at the foot of the moss-stuffed bed. Then, choking on her sobs, she struggled onto the bed and across my daddy’s legs. She grabbed on to them as if she could pull him back from the other side; But she could only lay there wailing tattered pieces of her heart. I stood wondering why my daddy couldn’t pick up those pieces like he had so many times when the heat of the fields had sunk her low. Hold her sobbing head? Wipe her tears away? Because only her silent cries were left and even those were all but spent.

My daddy still stared up at that small hole in the timbers that surrendered a glint of light over his brow. Alex yet sat in the corner where he’d pulled himself tighter into his arms. There was little to go.

“Why ain’t you out in the fields?” Burney demanded. “This ain’t Sunday. Isaac’s knows to get them crops in before the first rains. I’ll cut you off all food credits if you don’t get out there, and I mean now!”

But we knew what he meant even before he spewed the words. His glaring eyes spoke louder than his voice. Burney’s words were hard, mean and therefore true to his deepest heart—that part of his soul that could not follow Jesus to the doorsteps of the downtrodden. So why do I yet look back after all these years searching for a glint of tenderness in his eyes, a drop of humanity somewhere in his uttering? ’Cause there was so much from his seven-year-old son? The heat of his anger singed my thoughts for I quickly realized where the ugly words that ol’ Isaac openly spewed at the ’croppers came from; they were born from the very depths of the soul of one Robert Burney, former slave owner. And I also knew why he didn’t mouth them himself. For those deeds he had Isaac around so his Christian mouth remained unsullied by the coarseness that his wife would surely claim to be offended by. But then maybe a mouth roughened by coarse words can’t savor a mint julep. How could I have known?

The ’croppers withdrew in silence. Minerva moaned and choked as Burney stared on. His mouth twitched and his words fumbled as they reloaded.

“Owen, he dead…” Momma whispered.

Now like Alex she cried with no tears.

“He gone to Jesus. Now you ain’t got ’im no more. No, you ain’t!”

Her words were tangled in her sobs but still hit the walls like an ax hits dry timber and landed, splinter by broken syllable. I stood there fearful of my heart bleeding me away till nobody could see me. Not my daddy for sure. His still open eyes could see me no longer, and I yet begged for him to.

Burney jolted the way Miss Burney always did at the sight of me in her rose garden.

“Fever! Damn you!” Burney yelled. “You brought me to a shack with the fever! Look at you, you got it too!”

He reared back from Owen’s stare.

“Owen dead…” Momma repeated; her sinking eyes still pleaded. But Lord, it was all too late.

I always cried when Alex did—figured I could rely on his instincts. That day I would have cried all the same as I struggled to sort the whys. Why was my daddy sleeping with his eyes open? Why was Alex sobbing so pitifully? Why did Momma seem lost and so far away?

“Don’t…don’t separate my kids. Don’t run ’em off like stray dogs. We been workin’ all our days fer you. Jesus is watchin’!”

Momma lilted to her knees, like she always did when she prayed, but there was no prayer left. She crawled over to clutch at Burney’s ankles and beg for something that was too broken to possess again. Her twisted body folded at his dusty boots, which brought the look of terror to Burney’s ashen face. Still I wondered how he would comfort her? Wipe her tears on the sleeve of his white shirt like he did Jackson’s nose? Was he gonna sit a spell to offer thanks for all the years of work he’d squeezed out of Owen Breedlove? No, that was not why he’d come to our shack. There were no flowers hidden in his clinched fists or tenderly arranged somewhere his bitter words.

“Ain’t nobody in the world watchin’ a nigger die!”

But, Lord, somebody was watching. With my own eyes I’d seen much, and no, there was nobody counting. Not the life of Owen Breedlove; nobody but Jesus that is. Tell me what dying is? Why is Burney mad at Momma? I could no longer cry as loud as my brother, yet I still tried.

Momma mumbled broken whispers to comfort Alex and me.

“The Lord is my Shepherd. Though I walk through the shadow of death…”

But I reckoned the words were too brittle for the Lord to hear, even if He wanted to.

Momma’s face screamed, but her words only crumbled to the ground next to her mouth. “God is watchin’ you!”

Minerva Breedlove died the next day.

Something was gone, but how could I have known that it was my childhood?

THE AIR BETWEEN OUR TUBS: Borrowed Dreams

The novel is narrated by the protagonist herself, in a style infused with all the wit and wisdom she needs to draw on to survive the trials she encounters. The music of the prose captures the verve and passion of the lives it traces, and the arc of the narrative follows an epic trajectory, encompassing a vision as broad and embracing as the love that animates her awareness.

Winner of the Hackney Literary Awards

The Air Between Our Tubs explores the depths of human depravity, and the resilience that enables us to triumph over it. In situations of the most dire violence and inhumanity shines a gleam of love, endurance, and commitment to a belief in the possibility of goodness. The novel is a testament to the capacity of these values and beliefs to persist and overcome in the face of the evil they encounter. Despite the heart-wrenching realities it explores, The Air Between Our Tubs is a book of profound hope and ultimately a love story. LEWARO ROAD

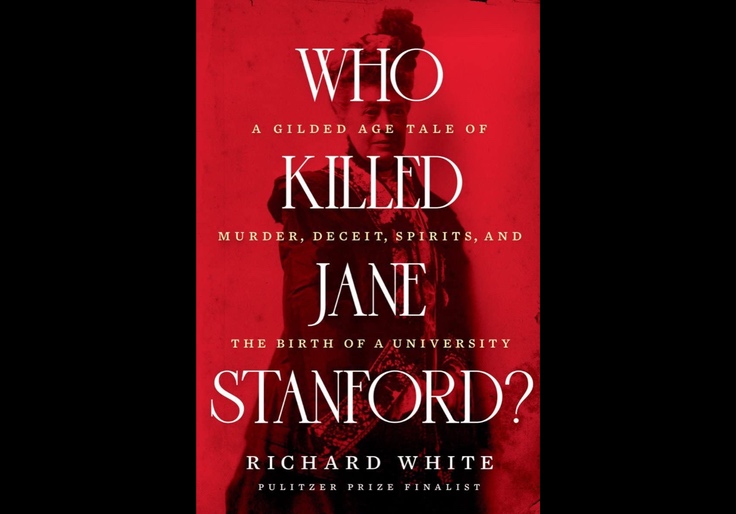

NON-FICTION: WHO KILLED JANE STANFORD?

A Cardinal Sin at Stanford University

Jane Stanford could have been saved by a fart. That, at least, is what her doctors, friends, and community accepted in 1905 when the cofounder of Stanford University spoke her last words: "This is a horrible death to die."

A physician claimed that Mrs. Stanford overate at lunch and had considerable gas, which prompted a heart attack. The president of Stanford University refused to accept that Jane’s death was unnatural. Members of the Stanford family repeated the lie that Jane died of heart failure.

Historian, Stanford University professor, and two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist Richard White rejects this relayed account and swaps it for one more interesting: murder. As White explores in his new book Who Killed Jane Stanford?, the philanthropist had powerful enemies. Many of them were involved in an elaborate plot to kill the heiress and seize her estate for themselves. In his detailed account of the Gilded Age mystery, White dives into the century-old cold case and at last names a killer.

Just before bed on the evening of January 14, 1905, Jane drank from a glass of Poland Spring water. She immediately detected bitterness and began to vomit. Jane called in her secretary Bertha Berner, who agreed that the water tasted peculiar. Toxicology reports showed that Jane was poisoned by strychnine, a chemical commonly found in rat poison. She survived that occasion.

To recover from the stress of the incident, Jane vacationed at the Moana Hotel in Honolulu, Hawaii. On February 28, just six weeks after she was initially poisoned, Jane retired to her bedroom and drank from a glass of bicarbonate mixed with water. She immediately became ill. Jane again summoned Bertha Berner, who witnessed a series of spasms, during which the heiress declared she had again been poisoned. By the time doctors arrived, it was too late. Physicians concluded the cause of death was a lethal dose of strychnine.

Thousands of miles away in California, Stanford University officials clamored to rule the death natural. A classified murder or suicide could prohibit the university from receiving the widow’s estate—and university president David Starr Jordan couldn’t afford that risk.

It was 20 years earlier that Jane and Leland Stanford founded Stanford University. The couple established the college in memory of their son Leland Jr., who died of typhoid a year earlier. When her husband passed, the college became for Jane "the memorial of a dead son, and of a dead husband."

Jane was intimately involved in Stanford’s affairs, which, according to the author, vexed Jordan. When she questioned a faculty pick or an administrative decision, it demanded from the university president an agreeable response.

Jordan was a eugenicist who thought the French "dissolute and slovenly,' he despised southern Italians, and he thought Mexicans were ‘ignorant, superstitious, ill-nurtured, with little self-control and conception of industry or thrift.'" He also viewed Stanford as constantly overstepping her authority—but Jordan subordinated those views in exchange for the cushy title. He ignored Jane’s concerns over college management until she threatened that position. He even "said in confidence to certain students that things would be better at the University when she had passed away."

The president was no stranger to scandals, including the abrupt termination of faculty members for representing opinions contrary to the administration’s. In 1903, a professor blamed the "liar, hypocrite, and coward" Jordan for his unusual power to haphazardly hire and fire faculty members. Jane planned to terminate Jordan shortly after her February trip to Hawaii.

The control Jane sought in the university’s inner workings alarmed Jordan. She could be temperamental and selfish, and, with such a large chunk of the university’s endowment under her control, Jordan had to be strategic in their partnership. But the president wasn’t the only person close to Jane who manipulated her for money.

Jane paid well her close friend and personal secretary of 30 years, Bertha Berner, who accompanied her on many overseas travels, including that last and fatal trip to Hawaii. Berner inherited $15,000 and a home when the heiress died—and the maid was present for not one, but two instances in which her boss was poisoned.

White introduces a host of other players who likely played a part in Jane’s death: the corrupt law enforcement officers who botched the investigation, shady private detectives who ignored toxicology reports, house servants who stood to gain substantial inheritances. All of these fall short next to the killer White finally names.

Jane dedicated herself, her wealth, and her family’s memory to the university. A staunch spiritualist with Christian influence, she was "as close to Catholic as a Protestant could be." The Stanfords claim that their deceased son visited them in a vision and encouraged the couple to live for humanity and "build a university for the benefit of poor young men, so they can have the same advantages the rich have."

Jane Stanford lived for humanity. But in death, humanity deserted her. White’s investigation is a thrilling tale of Gilded Age deceit, wealth, and death. Rest assured, his conclusion is much more riveting than flatulence.

Who Killed Jane Stanford? A Gilded Age Tale of Murder, Deceit, Spirits and the Birth of a University

by Richard White

W.W. Norton, 384 pp., $35

No comments:

Post a Comment